CSM Thurman C. Cousins, U.S. Army (Retired) Professional Soldier Through to the Core

I’ve had the honor of interviewing numerous veterans. Many were citizen soldiers, drafted in times of national need and answering our nation’s call. When their tours of duty ended, they returned home and got on with their lives. I could tell right away Command Sergeant Major (CSM) Thurman C. Cousins was different. Battle tested in two wars, he was the type of larger-than-life leader who stood firm under fire and spit in death’s eye. His men recognized it too and they instinctively followed him. They succeeded in battle because of his leadership and he helped them come home alive. Yet he is humble and unassuming—the kind of soldier you want to have on your side. This is his story.

Thurman was born in Oklahoma during the depression, the oldest of nine kids. His parents were itinerant workers, sometimes scrounging the already-harvested cotton fields for left-behind cotton bolls and earning a penny a pound. By 1947, his parents had saved enough money to lease a 1400-acre farm in Kaufman County, Texas, about 70 miles southeast of Dallas. Settling down allowed the children to finish school, and in June of 1950, Thurman graduated from Scurry-Rosser High School along with the seven other members of his class.

Thurman was seventeen when he graduated and the youngest in his class. The other boys in his class had already been drafted and Thurman knew he would be too once he turned eighteen. Rather than wait for his birthday and then have to ship out on his own, Thurman enlisted in the Army on June 16, 1950, and went off to basic training with his friends. Just nine days later, North Korea invaded South Korea and the Korean War began, sealing Thurman’s destiny.

After completing basic training at Camp Chaffee (now Fort Chaffee), Arkansas, Thurman and the other newly minted soldiers were given eight days leave to visit their families before they had to report to Oakland, California, to board the fast transport ship USS General M. C. Meigs on their way to Korea via Japan. When the ship arrived in Yokohama, the men were directed off the ship and into a big metal building with Military Police (MPs) posted all around in case anyone had any second thoughts about going to Korea. Once inside, they were issued a duffel bag containing clothing, a back pack, an M1 Garand rifle, and ammunition. Knowing that they would be heading directly into combat, they had to leave most of the clothing behind, taking only spare socks, wool long johns, and a trench coat. They received any necessary last-minute shots, which Thurman remembers being particularly painful. They then loaded on ships and headed for Korea.

Thurman and over 5,000 other soldiers aboard the USS General M. C. Meigs sailed to Korea and arrived in late November. They unloaded at the port of Inchon in South Korea, which on September 15, 1950, had been the site of one of Douglas MacArthur’s most brilliant military operations, landing troops behind the invading North Koreans and causing their rapid retreat across the 38th parallel and back deep into North Korea. When Thurman disembarked, he joined the 24th Infantry Division, which by this point was fighting the Chinese roughly in the vicinity of the 38th parallel and the “demilitarized zone” (DMZ) on the border between North and South Korea. Then, on January 1, 1951, half-a-million Chinese soldiers attacked the 24th Division and other United Nations forces, driving them south and once again capturing Seoul. Thurman remembers passing through Seoul, which had been reduced to nothing but rubble.

In addition to watching aerial dogfights between U.S. and Chinese fighters overhead, Thurman remembers the bitter cold of the Korean winter. Temperatures fell into the negative double digits, and the soldiers weren’t dressed or equipped to withstand the intense cold. Thurman eventually had to be evacuated to a field hospital because of frostbite. The field hospital tents were a good place to warm up because they were heated by oil burning potbellied stoves. The heat worked for Thurman, as he fully recovered and returned to his unit. Other soldiers weren’t so lucky—their frostbite cost them their fingers and toes.

In February and March of 1951, the 24th Infantry Division helped the United Nation’s forces push the Chinese out of Seoul and back across the DMZ into North Korea. Then in April, the 24th and 25th Infantry Divisions were nearly cut off by the Chinese, forcing them again to withdraw. During the retreat, Thurman’s unit dispersed to avoid capture. He remembers climbing a nearby mountain with two other men because they believed from that vantage point, they would be able to better chart their escape route and return to U.S. lines. When they reached the top of the mountain, they found eight U.S. Air Force airmen running a communications relay station. The airmen shared their rations with the weary soldiers and committed to helping them get back to their unit when they made their next supply run.

When it came time to depart, the soldiers loaded into a three-quarter ton truck driven by the airmen and headed out. Almost at once, the truck hit a landmine, lifting it up and tossing it into a creek bed. Thurman was pinned underneath the truck’s windshield with his head under water, but he was able to work himself free. Miraculously, everyone on the truck survived and they continued on their way, walking ten miles until they met up with a signal battalion with the 8th Army. They transferred Thurman to the 1st Cavalry Division, who sent him back to Japan, where he was issued clean clothes and new boots and got a few more painful shots for good measure.

Thurman returned to South Korea with the 7th Cavalry and stayed with them for the rest of the war, fighting up and down mountains in the vicinity of the DMZ. The war was largely a stalemate by this time, with the hills around the DMZ repeatedly changing hands between the United Nations and Chinese forces, depending upon who launched the offensive. Finally, on July 27, 1953, the United Nations and North Korea signed an armistice, with both sides taking up permanent positions along the DMZ near the 38th parallel.

Thurman was finally able to return home on November 23, 1953. He was initially processed through Japan, but then returned to the United States via ship to Oakland, California, where his journey began three years before. Upon his return, he was issued a new Class A uniform, which looked and felt good, and he headed home to Scurry, Texas, to be with his family.

Although being back with his family was good, Thurman had trouble finding a decent job. He lived in farm and ranch country, so he took the only job available—working as a ranch hand. He worked seven days a week from 6:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. for just $2.00 per day. One day he told his mother he couldn’t take it any longer—he was going to reenlist in the Army. A heated argument followed, but the next day, Thurman marched down to the recruiting station and made good on his pledge. He passed his physical the same day and soon found himself on a bus to Fort Hood, Texas, then Fort Bliss, Texas, and finally to a World War II era training camp in New Mexico. He spent four years there in a barracks so rickety that he had to shake the sand off his blankets every morning and take a bus to Fort Bliss just to wash his clothes.

Then, in February 1957, an opportunity arose that changed the direction of Thurman’s career. The 1st Battalion of the 40th Field Artillery (1st/40th) was being reactivated at Fort Bliss, Texas. Given Thurman’s combat experience in the Korean War, he was offered the chance to help reactivate the unit. During the week at Fort Bliss, he learned to fire the 105-millimeter howitzer. On the weekends, he earned an extra $10/day operating the base switchboard. As his Army pay was only $51/month, the extra $20/weekend was a real boost to his disposable income. A major also gave him some books on artillery and fire direction. He studied the books intensely until he knew them inside and out. He soon knew more about the new unit’s guns than all of his peers and was promoted to Sergeant (E-5).

The 1st/40th was officially reactivated on June 25, 1958. The following year, Thurman was sent to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, for formal artillery training. There he learned to fire the powerful eight-inch M115 howitzer, which could fire a 200-pound projectile almost 10.5 miles. By the end of ten months, Thurman had become so proficient with the M115 that he could tow it into place with a five-ton truck and have it set up and firing within three minutes. Senior officers took notice, not only at his skill, but also at the pride his soldiers developed in doing their job well. Thurman’s ability to train and motivate his soldiers in this manner would be important throughout the rest of his career.

In the intervening years, Thurman, now married, completed an assignment in France and was stationed at Fort Sill, the home of the Army’s Field Artillery School. Thurman was assigned as a gunnery instructor because of his proven proficiency with the artillery’s big guns. He also bought a house in Lawton, Oklahoma, just outside Fort Sill, where he and his wife, Donna Jean, began raising their three children. They pulled up stakes in April of 1964 to go to West Germany, where Thurman was assigned to the 1st Battalion of the 36th Field Artillery (1st/36th). The unit fielded the M110 eight-inch self-propelled howitzer. Given Thurman’s experience, he was promoted to Sergeant First Class (E-7) and he did everything he could to become the best, most proficient soldier possible. The Army made that easy as the training in West Germany was intense, with Thurman spending as much as ten months out of the year in the field with his unit. West Germany was ground zero for the Cold War with the Soviet Union, so training in Germany was serious business.

In February 1966, a one-star general from the 7th Army visited Thurman’s unit in a jeep because of the other serious business going on in the world—the Vietnam War. The general announced that the Army needed the unit’s officers and non-commissioned officers (as a First Sergeant, Thurman was a non-commissioned officer, or NCO) for service in Vietnam. Thurman was issued orders and given seven days to depart Germany with his family and report to Fort Dix, New Jersey. They somehow made it out on time, even arranging for their vehicle to be shipped back to Philadelphia. When they arrived at Fort Dix, they were told report to Fort Hood, Texas, so he loaded his wife and three kids, and all of their baggage, onto a bus to Philadelphia to pick up their car. Unbelievably, it had already arrived and they hopped in and drove from Philadelphia to Fort Hood. When they arrived in Fort Hood, they were told to turn around and go to Fort Sill, where Thurman would once again help reactivate the 1st/40th Field Artillery, which had been inactivated since April 1963.

As one of the first NCOs to arrive, Thurman had lots of responsibilities. He was assigned as First Sergeant for Alpha Battery, which had six M108 self-propelled 105-millimeter howitzers. These big guns, which had a crew of seven, could fire a 33-pound explosive projectile up to seven miles. Bravo and Charlie Batteries added six more M108s each, for a total battalion firepower of eighteen guns. When the 1st/40th had a sufficient skeleton crew of officers and NCOs, a cadre of draftees arrived fresh out of boot camp to man the unit. Thurman took his new soldiers to the west end of Fort Sill and spent the next eight weeks training them on the M108. He admits he was tough on them, but he taught them everything he knew about the guns and how to be successful in combat.

Thurman cannot say enough about the soldiers he trained during the summer of 1966. He talks about them like a proud parent, noting how dedicated, hard-working and eager they were. He remembers on one evening, allowing them to load into trucks to drive back to Fort Sill for an evening off. He told them he wanted everyone back by midnight. At 11:45 p.m., he heard the trucks returning with all the men singing, apparently feeling good after downing a few 3.2% beers back at the post. The next morning at roll call, he learned they were missing one soldier. The soldier turned up, though, as he’d fallen asleep in the truck on the way back to the training site, so technically he and everyone else was back by midnight.

The 1st/40th finished its training in September 1966 and, after seven days of leave, started the trip to Vietnam. Since the entire unit and its equipment needed to be deployed, all of the men flew to Oakland, California, where they boarded a ship which already had their M108s loaded onboard. After a brief stop in Okinawa, the ship arrived in Da Nang, South Vietnam, in October 1966. The Navy transferred their M108s to smaller boats that looked like World War II landing craft and convoyed them up the coast to near the demilitarized zone (DMZ) between South and North Vietnam.

Once the M108s were unloaded, Alpha Battery was directed to establish a position on a nearby hill. When they arrived, Thurman told his men to dig positions deep enough so when they lay in them, they would be completely below ground. They finished their work around midnight, which was good because they next night they came under attack from enemy fire from the North Vietnamese side of the DMZ. In fact, during the course of the next year, the three batteries of the 1st/40th were constantly under fire from enemy rockets, mortars, grenades and small arms.

To help fend off the small arms attacks, each battery was issued a 40-millimeter gun to patrol the vicinity around their fire bases. Thurman remembers meeting a staff sergeant in charge of one of those guns. He had twenty-five years in the Army and was getting ready to retire in three months, but was killed on one of the missions. The memory of that staff sergeant has stuck with Thurman all of these years.

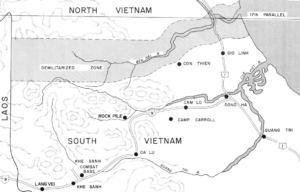

During Thurman’s time with the 1st/40th, the batteries provided fire support for the 3rd Marine Division. They fought in places with names like the Rock Pile, Khe Sanh, and Con Thien. Wherever the Marines went, one of the 1st/40th batteries went with them. The batteries did not fight from the rear—they fought from the front—and as a result, they lost twenty men killed in direct engagements with the enemy.

As the 1st/40th neared one-year in country and many of the unit’s original members had either been lost or rotated back to the States, the unit’s commanding officer, Colonel Lee Roper, asked Thurman to stay on as his Battalion Sergeant Major (the senior enlisted member of the command) until a new sergeant major arrived. Thurman agreed because he had a special bond with Colonel Roper, as they were the only two members of the command who had served in Korea.

One morning, Colonel Roper told Thurman to fill up his jeep with ammunition because they were going to Cam Lo. There were special forces soldiers there and Colonel Roper had promised he would watch out for them. When they arrived, there were no Americans there, as one of the special forces soldiers had been killed and the others had already withdrawn. Sensing they were not in a good place, Thurman manned the machine gun on the back of the jeep with a full belt of ammunition and prepared to fight their way out. He said if a rabbit had jumped out and surprised him, he’d have shot every hair off of it. Fortunately, they made it back to base camp without incident.

In November 1967, a new Sergeant Major arrived and Thurman was allowed to go home. He also found out he was on the promotion list to Command Sergeant Major, the highest enlisted rank in the Army. His initial assignment was in Fort Sill as the Sergeant Major of the 3rd Corps Field Artillery, but in the summer of 1968, he received orders for his second tour in Vietnam. This time, though, he would serve with the 1st Cavalry Division, which was the unit he’d met up with in Korea after evading capture by the Chinese. Once in country in South Vietnam, he went through a quick jump school, practicing repelling and jumping from a tower with a parachute. He was assigned to Alpha Battery of the 1st Battalion, 77th Field Artillery (1st/77th), firing the lightweight M102 105-millimeter towed howitzer.

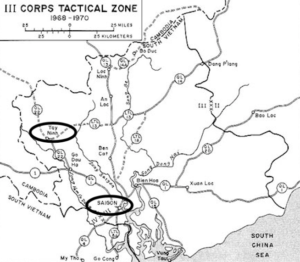

The 1st/77th served in the III Corps area of Quan Loi, which is about sixty miles north of Saigon and ten miles from the Cambodian border. The unit’s mission was to support the 1st Air Cavalry Division. Thurman was involved in combat operations throughout 1969, including fighting the North Vietnamese Army in November 1969 at Tay Ninh, which is right on the border with Cambodia. During that engagement, Thurman’s unit came under an intense nighttime attack, during which Thurman was wounded from the blast of a shotgun. The North Vietnamese soldier paid for the shot with his life, and Thurman confiscated the shotgun and still has it to this day.

After a brief stint back in Fort Sill from December 1969 to the end of February 1970 while on special leave, Thurman reported back to his unit in Vietnam. In May 1970, Chinook helicopters airlifted the six guns of his battery into Cambodia with the 1st Air Cavalry Division. Although they were subjected to constant attacks from the enemy, they captured and destroyed a massive North Vietnamese supply base dubbed “Rock Island East” before pulling back to Vietnam in June. They’d been in Cambodia nearly sixty days, all the time under fire and returning it in kind.

After completing his tour in Vietnam, Thurman returned to Fort Sill, where he again had the opportunity to work with Colonel Roper. He was given responsibility for training 800 soldiers every eight weeks on the art of field artillery. He did this for eleven months, before transferring to the Arkansas National Guard. Then, in 1973, he was selected to attend the Army’s new Sergeant Major Academy at Fort Bliss, Texas. He completed the course in six months and, after a short tour at Cornell University working with ROTC cadets, he transferred to the 10th Special Forces in Italy. This assignment truly was special, as he traveled to Turkey and other countries in the region in civilian clothes supporting nuclear capable Sergeant missiles. Finally, on August 1, 1975, in Fort Sill, Oklahoma, at the age of forty-two and after twenty-five years on active duty, Thurman retired from the U.S. Army.

Now a civilian, Thurman took a position as a major in the Texas Criminal Justice System in Huntsville, a job that allowed him to attend college. He eventually earned his Masters degree and Bachelors degrees in 3 subjects, before taking his final assignment as a member of the Texas State Mounted Patrol. After training more than 5,000 people and 4,000 horses in several states, Thurman retired after twenty-two years. He now lives in his hometown of Scurry, Texas. Although his wife, Donna Jean has since passed away, Thurman is fortunate to have all three of his children living nearby.

Voices to Veterans salutes Command Sergeant Major Thurman C. Cousins, U.S. Army (Retired) for his many years of distinguished service to our country and to the people of the State of Texas. After fighting in two wars and earning six Bronze Stars with Vs for valor and countless other decorations, it is time for a grateful nation to say thank you for a job well done. Although we can never repay you for your sacrifices and the sacrifices of your family, we can make sure that your story is never forgotten.

If you enjoyed Thurman’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.