Petty Officer Second Class Arnold Fernandes, U.S. Coast Guard – From the Aleutian Islands in World War II to the Korean War

The bravery of the men and women in the United States Coast Guard is legendary. They set sail in the most hazardous weather conditions to rescue mariners and migrants at sea and to interdict smugglers trying to bring illegal drugs to our shores. The Coast Guard is also a military service, with ships and crews in harm’s way taking the fight to the enemy sometimes far from our shores. No story better exemplifies the bravery, heroism, and commitment of the men and women of the Coast Guard than that of Petty Officer Second Class Arnold Fernandes, who served in the Coast Guard during World War II and the Navy during the Korean War. This is his story.

Arnold’s parents immigrated to the United States from Portugal, initially settling in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where Arnold was born in January 1924. Arnold’s father was a commercial fisherman, plying his trade in the unforgiving waters of the north Atlantic until 1926, when he moved the family to the more hospitable environment of southern California. There they settled into the Portuguese fishing community of Point Loma, a beautiful, hilly peninsula bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the east by San Diego Bay. Arnold lived in Point Loma through his junior year of high school, but moved to Chula Vista in San Diego County for his senior year. He graduated from Sweetwater High School in June of 1941 and enrolled in the fall at San Diego State College.

After a little more than a year of college and with World War II raging in Europe and across the Pacific, Arnold and three of his best friends from San Diego State decided to enlist in the Coast Guard. The Coast Guard was well-respected in the fishing community, and Arnold held it in high esteem. In fact, in the late 1930’s, the Coast Guard saved his father’s life after his father became very ill on his fishing vessel while operating off the coast of Mexico. So, it was only natural that on November 5, 1942, Arnold raised his right hand and answered the Coast Guard call of duty. Without being given uniforms or training, he and his three friends were immediately sent to the Coast Guard Cutter Perseus, which was homeported in San Diego. Arnold became a “sonar striker”, which meant he would be trained to send high-pitched pings through the water using the ship’s sonar equipment. When the pings bounced off the hull of a lurking submarine, he could pinpoint its location and help vector his ship in for attack.

Unfortunately, sonar training wasn’t available on board the Perseus, so Arnold transferred to Naval Station San Diego to attend sonar school. He graduated in early 1943 with the rank of Petty Officer Third Class, and, with a logic only those who have served in the military can appreciate, was detailed to a small patrol boat in San Pedro, California, that had no sonar capability. Instead, he was given quartermaster duties, which meant he was charged with helping to navigate the boat. The boat’s Executive Officer was a famous actor, Henry Wilcoxon, who had leading roles in a number of Cecille B. DeMille films and also starred in movies with the likes of Vivien Leigh and Lawrence Olivier. Arnold remembers Wilcoxon getting a kick out of watching him dive off the ship’s bridge for man overboard drills.

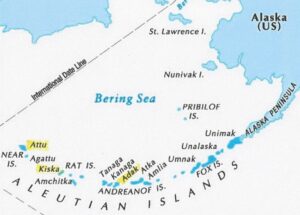

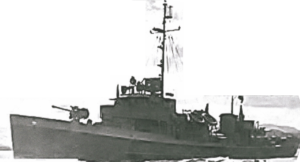

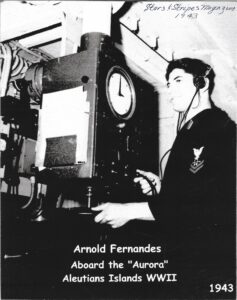

Patrolling off the coast of sunny San Diego in early 1943 was short-lived. After about one month, Arnold transferred to the Coast Guard Cutter Aurora in the Aleutian Islands. In a little known theater of the war, the Japanese had invaded the islands of Attu and Kiska in the Aleutians in June of 1942 as a diversion for their planned invasion of Midway Island, further south. That gave the Japanese bases on U.S. soil from which they could attack U.S. ships and facilities on other islands in the Aleutian chain. Arnold realized this first-hand when he arrived at the U.S. Navy base in Dutch Harbor on Amaknak Island en route to the Aurora. There he saw a repair ship smoldering after being bombed by the Japanese. With the smoke rising over the harbor, Arnold realized for the first time he was in the middle of a war. He continued west to the Navy base on Adak Island, where the Aurora was homeported. This time the ship did have sonar, as its primary duties were anti-submarine patrol, search and rescue, and escort duty.

In May of 1943, the Aurora sailed with the U.S. task force charged with retaking Attu and Kiska Islands from the Japanese. The U.S. landed troops on Attu Island on May 11, 1943, without adequate equipment and under horrible weather conditions. The operation culminated on May 29th, when the Japanese commander led one of the largest Banzai attacks of the war against the unsuspecting Americans, breaking through the American lines and into the rear echelon. The attack was subsequently beaten back with heavy losses and complete annihilation of the Japanese attackers—only 28 enlisted men survived out of a force of around 2500. The U.S. suffered nearly 4,000 casualties retaking Attu, including 549 killed in action. The invasion is seared in Arnold’s memory.

Several other events stand out for Arnold in 1943. On one occasion when the Aurora was patrolling off Attu Island, Arnold was serving as the duty sonarman and made a definite contact with what he believes was a Japanese two-man submarine trying to position itself to torpedo the Aurora. The Aurora went to general quarters and the crew manned all the ship’s guns. The ship also dropped depth charges and fired hedgehogs, and eventually the hedgehogs scored a hit, exploding when one made contact with the submarine. Although Arnold does not believe the engagement was recorded in the ship’s log, he is certain of both the contact and the resulting hit.

On another occasion, the Aurora rescued the crew of a downed PBY Catalina patrol aircraft. The plane’s crew was laying on the wing, half-frozen in the frigid weather off the Aleutians. Then, on July 19, 1943, the Aurora was called upon to rescue the crew of the cable laying ship Dellwood, which had struck a rock while laying cable between Dutch Harbor and the outlying Aleutian Islands. The Aurora saved the crew without loss of life, but the Dellwood sank in Massacre Bay, the site of the U.S. Army’s landings on Attu Island.

Arnold’s most harrowing experience occurred on December 11, 1943, when the Aurora and the other ships in Task Force 8.6 were ordered to return to Adak Harbor to seek shelter from a mammoth storm heading toward them with 200 mile-per-hour wind gusts. On the way to the harbor, the Aurora’s starboard side started to ice up and the ship began to list from the weight. With the wind and waves tossing the 165-foot vessel to and fro, crewmembers went onto the main deck and, after securing themselves with safety lines, began to chip away the ice using fire axes. Although they were able to clear away a lot of the ice, the seas became so rough that the Captain gave up the effort and ordered all hands below deck. The men were further directed to secure all watertight hatches.

Miraculously, the Aurora made it safely to Adak Harbor with the rest of the fleet, consisting of battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and support ships. However, unlike the rest of the fleet, the Aurora received orders to immediately turn around and search for two missing Liberty ships believed to have cracked in half with their crews in imminent peril of loss. When the Captain asked if there was time to take on fresh water and fuel, he was told “no, carry out your orders.” The Captain did, again ordering the crew below deck with hatches secured, and the small ship set out into the raging storm.

As the ship made headway, Arnold stood duty in the sonar room located just behind the bridge. It was then that the Captain and the Executive Officer entered the compartment and put the Aurora’s documents into a two-foot-wide by three-foot-long by two-foot-deep brass box with one-inch holes drilled into it. Arnold hadn’t paid much attention to the brass box before, but now he realized it was designed to make sure the ship’s papers and codes would not float to the surface and be captured by the Japanese in the event the ship sank. He also realized the Captain’s and Executive Officer’s actions meant they both believed there was a good chance the ship would be lost in the storm.

The Aurora’s orders were to look for the Liberty ships SS John P. Gaines and SS Chief Washakie. They never found the John P. Gaines because it had actually broken in half and sank on November 24th with the loss of ten crewmembers. As the weather began to subside, they did find the Chief Washaki, a 422-foot Liberty ship built in 1942, with her bow starting to break away just forward of the bridge. Fortunately, the crew was safe and had secured the bow to the hull using chains to keep it from completely breaking away. Given that the Aurora was less than half the size of the Chief Washaki, she was unable tow the damaged vessel to safety. So, with the Chief Washaki crew safely manning the damaged ship, the Aurora stood by until help arrived.

After the Chief Washaki rescue, the Aurora returned to Adak and then sailed to Bremerton Naval Shipyard in Seattle, Washington, to repair the damage it sustained in the storm. The Aurora had lost all her lifeboats, her decks were warped, and the ship’s three-inch guns were torn loose from their deck mounts. Arnold and his fellow crewmembers do not know how the ship stayed afloat, but they thanked God for her seaworthiness. In fact, one of the crewmembers wrote a poem about the resilient little ship: “The Aurora is a mighty ship we call the ‘A’. She doesn’t run on steam, she doesn’t run on hay. She just bobs around like a cork, that’s what we like about the ‘A’”. Another shipmate wrote on a Christmas menu: “After two years in the Aleutians there’s one thing we can tell, when we die we’ll go to heaven ‘cause we served our hitch in hell.”

Arnold did not escape his time on Aurora unscathed. During a storm, he fell down two decks and severely injured his tailbone. He was transferred to the Naval Hospital on Adak where he underwent three surgeries. After recuperating for one month, he was sent back to the Aurora, and then to Seattle, where he underwent yet another surgery and further rehabilitation. When he was finally released, he was given orders to the Coast Guard Education Office in Seattle, where he replaced a Chief Petty Officer being discharged. His duties involved checking in movie projectors from ships returning from duty and showing war documentaries to the Admiral and his staff.

Arnold was discharged from the Coast Guard on January 11, 1946. His father had become very ill from cancer, so Arnold hurried home to be with him. He did not make it in time—his father died while Arnold was on his way home from Seattle.

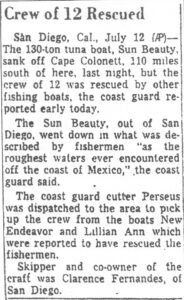

After the war, Arnold tried his hand at several jobs, including working on his brother’s 100-foot, 130-ton tuna fishing boat, the Sun Beauty, out of San Diego. On July 10, 1947, Arnold, his brother Clarence, and ten other crewmembers set sail from San Diego headed for the tropical eastern Pacific in search of tuna. Early on the morning of the 11th after Arnold had come off watch and bedded down, the ship began to roll in the heavy seas preceding a coming storm. One roll was so severe, it wedged Arnold against the starboard side of his bunk and the ship did not right itself. He roused the navigator sleeping below him and said the ship was about to capsize. They scurried out of the compartment just as water began to rush in.

When Arnold and the navigator climbed out onto the main deck, they found Clarence telling the crew to remain calm. He warned them not to jump into the water as they would likely never be found. Instead, after accounting for the entire crew, Clarence directed them to climb into the fishing net tender skiff, which was still seaworthy, before the Sun Beauty sank. For some unknown reason, Arnold salvaged a bottle of Seagram’s VO and a can of asparagus, but essentially everything else in the Sun Beauty was lost. Arnold can still picture the stern of the ship sinking below the waves, with the words Sun Beauty and San Diego visible until the very end. It only took fifteen minutes for the Sun Beauty to go down.

Clarence headed the skiff in the direction of the coast, but it was so slow and the seas so rough that there was no way they could outrun nightfall and the impending storm. They saw a couple of tuna boats on the horizon heading for the port of Punta Colonet in Baja California, but they could not attract their attention. Around 5:00 p.m., they spotted another boat heading toward Punta Colonet. Realizing this might be their last chance, Arnold picked up the can of asparagus, polished the top of it, and used it to flash an “SOS” in Morse code by reflecting the setting sun’s rays. Unbelievably, it worked, and the small boat turned in their direction. When the boat reached the skiff, its two-man crew threw a line to the skiff and towed it to Punta Colonet. The Sun Beauty’s crew was saved by Arnold’s quick thinking and a can of asparagus!

The next day, the Coast Guard Cutter Perseus, Arnold’s very first ship, arrived in Punta Colonet to take the crew of the Sun Beauty back to San Diego. The Perseus gave them each food and water and a pair of jeans and a t-shirt so they wouldn’t have to land in San Diego in their shorts. It’s hard to imagine, but Arnold had survived two years in the icy, war-ravaged waters around the Aleutian Islands only to almost be killed off Baja California’s sunny coast. It didn’t stop Arnold and his brother, though, as two weeks later they had a new boat, the Sea Wolf, and were sailing back to the eastern Pacific in search of tuna.

Arnold also was active in the Navy Reserve after the war, and he was recalled to active duty in the Navy as a Second Class Petty Officer from August 28, 1950, to February 1, 1952. This time he served as a sonar operator on the Destroyer Escort USS Walton, operating off the coast of California training submarines and sonar teams, and performing escort and other duties as assigned. He was formally discharged from the U.S. Naval Reserve on July 31, 1953.

After the Korean War, Arnold returned to the family business, working on Clarence’s commercial tuna fishing boat. He eventually transitioned to the Van Camp Sea Food Company as the Fleet Operations Manager, and retired in 1980 from Bumble Bee Sea Foods.

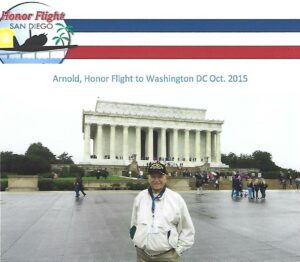

Arnold moved to Cardiff by the Sea in 1979, where he served as a director on the Cardiff Town Council. He is a life member of the Cardiff Chamber of Commerce, the Cardiff Town Council, and the Friends of the Cardiff by the Sea Library. As if that wasn’t enough, he is active in American Legion Post 416 in Encinitas, California. Arnold still lives in Cardiff by the Sea with his wonderful wife, Anna.

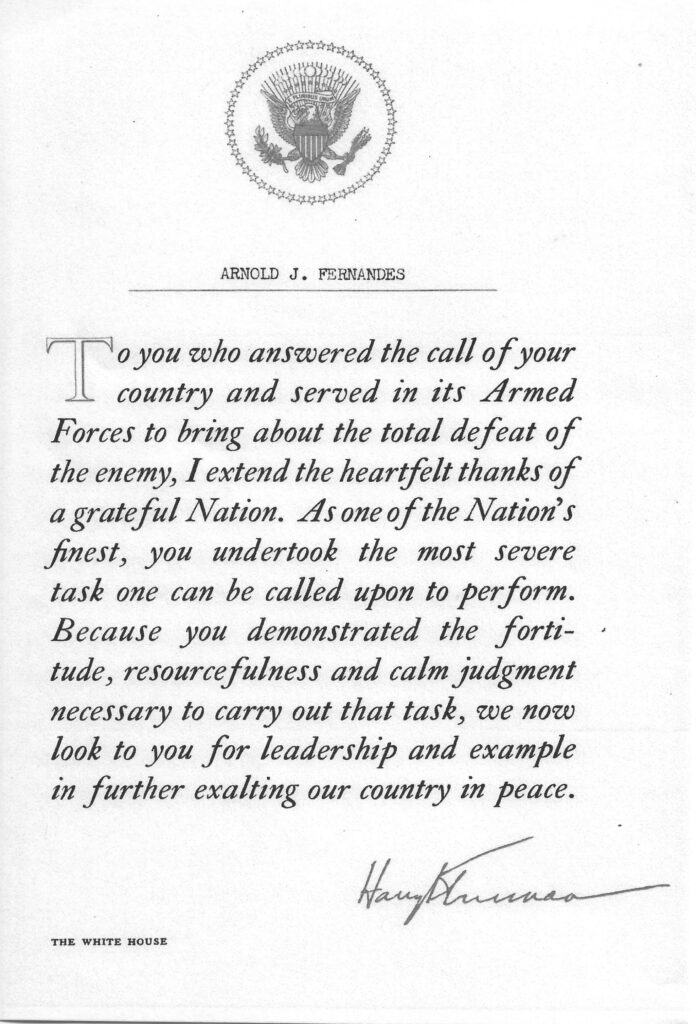

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Petty Officer Second Class Arnold Fernandes for his selfless service to our country in the Coast Guard and the Navy. He served with distinction in the unforgiving waters of the northern Pacific around the Aleutian Islands, knowing that every voyage could be his last and risking his life to rescue others from the perils of the sea. Even when he returned to civilian life, he continued to serve his community through both business and government. Arnold, we thank you for all you have done defending our freedom, and we wish you fair winds and following seas!

If you enjoyed Arnold’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.