Specialist Jack Murphy, U.S. Army – Saluting Fellow Veterans with a Heartfelt Song

Veterans instinctively understand each other. No matter who they are, where they come from, what their rank was, or what they did in the military, there is an unshakable bond between them. Explaining that bond can be difficult, but some people are gifted in conveying it in ways that help others understand. Specialist Jack Murphy, U.S. Army, has the gift. Twenty-five years after surviving war in the rice paddies and jungles of Vietnam, Jack wrote a moving tribute to his fellow Vietnam veterans called The Promise. The song has touched the hearts of thousands and was played during the Memorial Day remembrance ceremony at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC, in 1996. Jack could not have written The Promise without first having lived its lyrics. This is his story.

Jack was born and raised in Croydon, Pennsylvania, a small town about twenty miles north of Philadelphia. His father was a World War II veteran, having landed on Omaha Beach at Normandy and later fighting in the Battle of the Bulge. After the war, he worked for the Kaiser-Fleetwings Aircraft Company in Bristol, Pennsylvania. His mother stayed at home raising Jack and his brother and sister. Jack attended Delhaas High School and was really into music. He played in a number of bands outside of school.

By the summer of 1968, Jack could see the writing on the wall. He was working at a local cigar factory and all the young men his age were being drafted. He knew it would be only a matter of time before his number came up, too, so he tried to convince three of his buddies to enlist with him. After a few days of arm-twisting, all four young men went to the local recruiting center to join the Army. They took an aptitude test, signed a few papers, and it was official—they owed the next three years of their lives to Uncle Sam.

Jack and his friends reported to the Military Entrance Processing Station, or MEPS, in Philadelphia, on September 26, 1968. There they were given a physical exam, sworn into the Army, and loaded onto a train enroute to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, for Basic Training. As an eighteen-year-old kid traveling with his friends on a train, Jack found the whole experience exciting. All that changed when they got off the bus at Fort Bragg and met their platoon sergeant for the first time. They were definitely in the Army now.

Basic Training is still ingrained in Jack’s memory. He and his friends were assigned to the same platoon, so they were able to spend the next eight weeks together learning to become soldiers. One of the hardest parts for Jack was the physical training because he was not an athlete in high school. He was more into music and hanging out on the corner “looking good”. He and his friends managed to get through it, but graduation was where they parted company. Jack’s three friends went to helicopter schools, while Jack went to Advanced Infantry Training (AIT) at Fort Polk, Louisiana. Jack was on his own.

The AIT training at Fort Polk was known as “Tiger Land”. Its purpose was to train American soldiers how to fight and survive in Vietnam’s jungle environment. Jack describes it as “rough, very rough”. There he learned to conduct ambushes and to respond when caught in one. He also learned how to spot boobytraps by navigating through a course with boobytraps hidden along the route. Jack knew he had to master the skills if he was going to come back from Vietnam alive.

By the beginning of February 1969, training was over and it was time for the real deal. Jack went home for thirty days leave and at the end, said goodbye to his family at the airport in Philadelphia. His father, knowing better than most what Jack was about to go through, simply said “be careful” as tears welled up in his eyes. His mother was less restrained and cried openly. Jack then boarded the plane for the first leg of his trip to Vietnam.

Jack’s plane landed at San Francisco International Airport. From there, he went to Travis Air Force Base, where he boarded a chartered plane along with lots of other replacement soldiers headed to Vietnam. The plane landed at Tan Son Nhut Air Base in the Republic of South Vietnam on March 5, 1969. When the door opened, the heat, humidity and smell of diesel fuel rushed in, engulfing Jack and the rest of the new arrivals. It was so overpowering, Jack remembers thinking “what kind of place is this?” He didn’t have long to think about it, because soon after he got off the plane, he and the other replacements were loaded onto a bus heading for the sprawling U.S. base at Long Binh. The bus windows were covered by a metal mesh to prevent grenades from being tossed inside—a grim reminder of the serious business Jack was about to become involved in.

At Long Binh, Jack reported to the 90th Replacement Battalion. As a replacement soldier, Jack did not know what operational unit he would be assigned to. Instead, he and the other replacement soldiers were temporarily assigned to the 90th Replacement Battalion to await their permanent assignment. While there, they in-processed and received additional instructions about their time in Vietnam, but mostly they waited anxiously until their name appeared on a bulletin board identifying the unit they would be joining. Jack only had to wait a couple of days before his name appeared. His new assignment: the 199th Infantry Brigade (Separate) (Light).

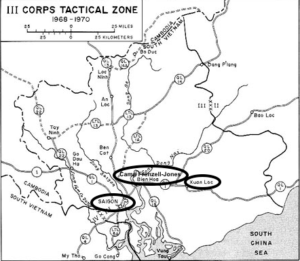

Jack was not the only replacement heading to the 199th Infantry. He and the other new arrivals climbed aboard trucks and headed for the 199th Infantry’s main base at Camp Frenzell-Jones. Once there, they went through a week of boobytrap and rifle range training, made more intense than their stateside training with the realization that now their lives depended upon it. With the refresher training under his belt, Jack boarded a CH-47 Chinook helicopter and headed out to Delta Company of the 5th Battalion, 12th Infantry, which manned a company-sized fire base in the rice paddies of the Mekong Delta.

When Jack arrived at the fire base, he was assigned to a squad and a bunker. As he started to talk to the men in his squad, he found them helpful, but they kept their distance. That is, they told him what to watch out for, but he soon realized they didn’t want to become close because they’d already lost too many friends. They told Jack to listen to the guys who’d been there a while and do what they did and he’d get through it. In other words, if Jack wanted to survive, he had to learn fast.

When it came time to bed down for the night, everyone laid down on the ground outside the bunker. Already concerned he was going to have trouble sleeping during his first night in the field, he asked why no one was sleeping in the bunker. His squadmates told him they slept outside because there were giant rats in the bunker. Later that night, the Viet Cong launched rockets at the fire base and everyone except Jack took cover in the bunker. Someone inside the bunker shouted at him to get inside, but he responded, “You told me there are rats in there.” The voice called out again, “Get in here, you dumbass. Would you rather get blown up or deal with the rats?” Jack joined his squad in the bunker.

The next day, Jack was assigned to work on a detail outside the wire (meaning outside the protective perimeter of the fire base) eliminating trees so there would be a clear field of fire around the base. After working for a while, his group was instructed to return inside the wire because a patrol was returning and they didn’t want any misidentifications or friendly fire incidents. When Jack returned to the camp, he saw the patrol emerge from the tree line. He asked the First Sergeant if that was the patrol they were expecting and just as he did, the returning patrol’s point man stepped on a Viet Cong boobytrap armed with a 105-millimeter artillery shell. At that exact moment, reality set in for Jack. He and those around him could be killed at any minute. All he could do was accept it and hope.

The next day, Jack joined his patrol on his first search and destroy mission, wading off through the rice paddies from the relative “safety” of the fire base in search of Viet Cong. The route took them over the area where he’d witnessed the boobytrap detonate the day before, only now it was he who was trudging through the dangerous terrain. On all such missions, the squad had to be ever vigilant, trying to detect and avoid the boobytraps they knew were there but could not see.

During the first three months of Jack’s tour, his squad deployed to different fire bases, sometimes using Boston Whalers and airboats to move around. Each of the airboats had a driver and a person riding shotgun to watch for snipers and boobytraps. On one occasion when Jack was preparing to go out on a patrol via boat, he learned that the person riding shotgun was going home, so they needed someone to replace him. Jack volunteered. After Jack and the driver dropped off the patrol, they returned on June 2nd, 1969, to take the patrol some cases of rations. When Jack got off the boat to deliver the rations, he set off a boobytrap, wounding him and five others. He had to be evacuated to the 3rd Army Field Hospital in Saigon, where he spent two weeks, and later to Cam Ranh Bay for two additional weeks. Jack would never volunteer for anything again. The only bright spot occurred in the 3rd Army Field Hospital when a famous singer from the 1930s-1950s, Tony Martin, visited Jack’s ward after a show and pinned a Purple Heart on Jack and the other wounded soldiers.

After completing his recuperation at Cam Ranh Bay, Jack returned to the 199th Infantry at Camp Frenzell-Jones. As soon as he arrived, he learned the unit was being deployed to the vicinity of Xuan Loc, northeast of Saigon in the III Corps area of responsibility. His new outpost was Fire Base Libby, located in dense triple canopy jungle. This came as a shock to the men in the unit, as they were used to fighting the Viet Cong in the rice paddies of the Mekong Delta and now they were being asked to fight North Vietnamese regular soldiers in the jungle. The new assignment called for different tactics but was just as dangerous—Jack’s unit sustained casualties on the first night it arrived.

Although the enemy, the terrain, and the tactics were different, the unit’s search and destroy function was the same. Jack and the other sixteen to twenty members of his platoon would set out from Fire Base Libby and patrol in the field for fifteen to twenty days, seeking to engage the enemy. At the end of that time, they would return to the fire base for three days to rest, get showers and clean clothes, and gear up for the next patrol. On these patrols, the danger was not so much from boobytraps as it had been further south, but from engagements with North Vietnamese units. This was Jack’s life for the next six months.

With thirty days to go on his Vietnam tour, Jack was able to take advantage of an Army program to help him earn his GED. Not only would this get him his high school diploma, but it also had the significant benefit of getting him out of the field. He studied for his GED during his final month in Vietnam, and he would later finish it at Fort Dix, New Jersey, after returning to the United States.

Jack finally left Vietnam on March 5, 1970, one year to the day after he arrived. He considers that day to be the best day of his life. He departed from Tan Son Nhut Air Base, retracing his steps through Travis Air Force Base, before flying home to his family in Philadelphia. He still had two years to go on his three-year enlistment, but the Army allowed him to work off the remainder of his commitment in the Fort Dix Commissary, which was quite a change from humping through the jungle as a radio-telephone operator just trying to stay alive. Jack was honorably discharged from the Army on November 2, 1971. His three friends who enlisted with him on September 26, 1968, also survived the war.

After the war, Jack returned to small town life north of Philadelphia. He married and had two children, and took a job working at a steel mill for U.S. Steel. After ten to eleven years, the market for American steel dried up and the mills closed, so Jack found a new job driving for the medical clinic at the Willow Grove Naval Air Station. He eventually retired from that position.

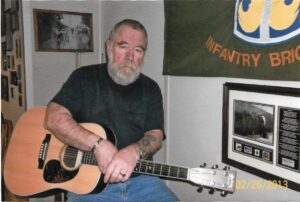

Although Jack left Vietnam in 1970, Vietnam did not leave him. In fact, he’d been going to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC, every Memorial Day and Veterans Day for years to pay his respects to his fallen comrades. He’d also wanted to write a song about his experience in Vietnam, but the inspiration wasn’t there. Then, one night in 1995, the inspiration suddenly came. Jack picked up his guitar, turned on his tape recorder, and in fifteen minutes created the music and lyrics for The Promise. He took the tape to a producer at a local recording studio who liked it so much he wanted to produce it. They spent the next two hours recording the final version. The Promise was later played during the 1996 Memorial Day Ceremony at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Since then, the song has spoken to thousands of veterans and their families about the lasting impact the Vietnam War has had on those who fought and served.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Specialist Jack Murphy for his service in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War. Despite being in constant danger and threat from enemy fire, Jack did his duty with bravery and distinction. Most important, he’s never forgotten those he served with, standing side-by-side with them in time of war and preserving their memory after his return. We thank Jack for his unselfish service to our country and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Jack’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Now, please enjoy the song The Promise, by Jack Murphy:

February 9, 2020 @ 7:22 AM

Is a fantastic friend and a fantastic guy I would love him to the end of time

February 15, 2020 @ 8:44 AM

Thanks so much. B/ 4/12 , 68-69. B troop 3/17 Cav, 71-72

February 15, 2020 @ 12:41 PM

Nelson – I really appreciate your service, as well.

February 18, 2020 @ 1:31 AM

I appreciate your service! I was a C-130 loadmaster. I loaded the one I was flying on! We delivered to the real heroes to their destination in the bush! We resupplied them daily where ever they were. The worst duty I performed was loading them in their body bags to carry them to their families back home. The C141sdelivered the back to the world! That’s what we called America while in Vietnam!

February 18, 2020 @ 9:37 PM

Venson – thanks for your service in Vietnam. The C-130 is an amazing aircraft. May I recommend that you also read the story about Lt Col John Heimburger. He was a C-130 pilot in Vietnam. It’s such a small world, perhaps you two might know each other. He flew out of Japan.

February 21, 2020 @ 10:12 AM

Thank you for your service. My father Mike yohn was a Marine in Vietnam and my grandfather was in the Navy in Vietnam and I’m very proud of them they are my heroes. Every time I see or talk to a service person I always thank them for their service. My great uncle lost his eye parts of his leg and arm his name is Randy Rundle they wrote a newspaper article about him in California where he lived. Thank you again for everything you did for our Country. God Bless

February 22, 2020 @ 10:08 AM

Tara – thanks for your comment and for reading Jack’s story. We really appreciate your family’s service to our country, and also for taking the time to thank veterans. It really means a lot and I’m sure you’ve brightened their days!