Lt. Col. John W. Heimburger, U.S. Air Force (Retired) – Staying One Step Ahead of Disaster in Vietnam

Military pilots are a breed apart. They are risk takers and, at least by my standards, fearless. They aren’t satisfied with just getting by—they need to grab life by the reigns and live it on the edge. That description fits Lieutenant Colonel John W. Heimburger, U.S. Air Force (retired), to a tee. From being awarded the Silver Star in Vietnam to climbing some of the highest mountain peaks around the world, John has done it all. Even more important, John has lived a life of service to his country and his community. I could tell when I was interviewing him that I was speaking to a great American. This is his story.

John was born in 1941 and raised in Tolono, Illinois, just a few miles south of the University of Illinois in Champaign. His dad did everything from drive a gasoline delivery truck to serve as the chief of the local fire department, while his mom worked at home raising John and his brother and two sisters. John learned the value of work at an early age, distributing grocery store handbills and earning a penny for each one delivered. He later became a paperboy for the Champaign-Urbana Courier. His paper route not only allowed him to save enough money to buy a bicycle, but it led to an event that changed his life forever.

When John was fourteen, he won a trip to Washington, DC, by recruiting new subscribers for the newspaper. One of the sites he visited during the trip was the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, where he witnessed the plebes (first-year midshipmen) trying to scale a greased granite monument to place an officer’s hat on the top. Not only was it entertaining, but the midshipmen’s spirit, camaraderie, and teamwork also really made an impression on John. Later in the trip, John’s group had its picture taken on the Capitol steps with Congressman William Springer, who represented Tolono in the U.S. House of Representatives. Congressman Springer asked John what his favorite part of the trip was, and John told him it was his visit to Annapolis. When Congressman Springer heard this, he asked if John would like to go there. John said yes. Then the Congressman asked if John would like to be a pilot. John again said yes. Congressman Springer concluded by saying, “Have your parents call me in three years when you are ready to go to college. We’ve got a new Air Force Academy in Colorado and I can help you attend.”

Three years later, after graduating from Unity High School in Tolono, John reported to the new Air Force Academy just north of Colorado Springs as part of its fifth class, the “Golden Boys”. He credits his success at the Academy to his parents for raising him with a sense of personal discipline and to the Boy Scouts for giving him the self-confidence and leadership skills he needed. He dove right into Academy life, playing defensive end on the football team and even meeting Navy great, Roger Staubach, on the gridiron. He also excelled at field hockey and was invited to join the U.S. Field Hockey Team for the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo. As if that wasn’t enough, he sang in the Cadet Chorale, marched in President John F. Kennedy’s inaugural parade, and received his diploma with President Kennedy standing nearby. After graduating, he married Susan Young, to whom he was happily married for eighteen years, in the Air Force Academy Chapel.

John next reported for flight training at Reese Air Force Base in Lubbock, Texas. There he spent approximately thirteen months learning to fly the Air Force’s first supersonic capable training jet, the T-38 Talon, which had only recently been introduced. John loved to fly and it soon became clear he was a natural pilot. He also liked to press the envelope, and on one occasion just after he soloed, it almost cost him dearly.

On that occasion, John flew his T-38 near its ceiling of 48,000 feet, turned off its IFF transmitter so his altitude could not be tracked from the ground, and put his plane into a dive. Once he got the jet going fast enough, he pointed the plane’s nose upward with afterburners on to see what would happen when he went above 48,000 feet. When he reached 53,000 feet—an altitude where he could see the curvature of the earth—one of his two jet engines shut down. Although he managed to restart it after dropping 20,000 feet, he was sure he’d be in serious trouble. To his surprise, no one noticed his exploit and he continued his flying career, now informed by what could happen if he exceeded aircraft limits. On a more somber note, John remembers standing at attention on the base’s parade ground to mark President Kennedy’s death in November 1963. He had now come full circle with the late president, having marched in his inauguration.

John graduated near the very top of his class from flight training, so the Air Force allowed him to choose the type of aircraft he would fly operationally. John picked the C-130 “Hercules”, a rugged four-engine turboprop transport plane designed to move and supply troops on short runways at or near the battlefield. He chose C-130s because he thought they would give him the best chance of getting into the Vietnam War—he was right! After completing his C-130 advanced pilot training at Sewart Air Force Base in Tennessee, he reported to the 35th Troop Carrier Squadron at Naha Air Base on Okinawa, arriving on December 31, 1964. Shortly after arriving, he was presented with a certificate for being the #1 graduate from his C-130 training class at Sewart.

On January 1, 1965, just twenty-four hours after arriving at Naha, John received a call at his quarters—it was time for his first mission. He reported to the squadron, got the C-130 ready, and lowered its cargo ramp. A black limousine approached and drove up the ramp until it was on board the plane. The cargo doors closed and the plane took off for Cambodia. After they landed, they opened the cargo doors and the car drove off.

The plane taxied near some woods to wait for the car’s return. Soon, a horde of people descended upon the crew seeking to sell them everything from food to souvenirs. One man approached John with a handful of stones. John found one that looked like a gray star sapphire that would fit his Air Force Academy ring exactly. He asked the man the price and the man answered $300. John told him he only had $37 (which was true), so the man left. A little later, he came back and dropped the price to $200, which John still could not pay. He came back a third time, only to get the same answer. When the limousine finally returned to the plane, the man came running back and sold John the stone for $37. Later in Tokyo, John replaced the original stone in his Academy ring with the gray star sapphire he acquired in Cambodia. He treats the stone with special respect, assuming that since it was an exact match for his Academy ring, it must have been recovered from an American serviceman killed in the war. It is one of John’s most treasured possessions.

John flew his initial C-130 missions as copilot, helping qualify him to fly later as the aircraft commander. That opportunity came on a mission hauling sandbags from Saigon to Da Lat, which was up in the mountains. John recalls there was extremely limited visibility and is certain that had it not been for the skill of his navigator, they would have abandoned the mission. Instead, they broke through the clouds a mile from the runway and made a routine landing on what had been a perilous flight. From this point on, John would fly as an aircraft commander.

Bad weather wasn’t the only thing trying to kill John. On June 24, 1965, John and his aircrew ate dinner at a floating restaurant on the Saigon river in Saigon. The next day, Viet Cong guerrillas blew up the restaurant, killing scores of people, including twelve Americans. John felt like that summarized his entire time in Vietnam—he was always just one step ahead of disaster.

By the latter part of 1966, the Air Force had lost so many pilots within South Vietnam proper that it held a lottery at Naha Air Base to recruit more. The pilots in John’s squadron were considered eligible for the lottery because, although they routinely flew dangerous missions in Vietnam, they were not permanently assigned there. For example, John’s typical mission schedule would be to fly to South Vietnam and stay in country for ten days, flying up to five missions each day. He would then return to Okinawa for a week, where his wife and newborn son were waiting for him, until it was time to begin the cycle again. Pilots selected in the lottery would transfer to Vietnam and remain there until their tour of duty ended.

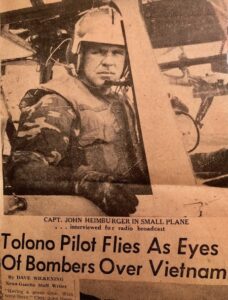

The names of the approximately 440 C-130 pilots on Okinawa were put into a hat and twenty names were drawn. John was one of the twenty and because he was junior in rank, he was assigned to fly as a forward air controller, or FAC. This job was extremely dangerous because it involved flying a very slow single-engine Cessna O-1 “Bird Dog” over the jungle, identifying and marking enemy positions with smoke rockets, calling in tactical airpower to attack the target, and then flying over the target again to assess and report the damage. Later, a slightly faster plane, the two-engine Cessna Skymaster was used, but the missions were still incredibly dangerous as evidenced by the need to replace the many pilots killed in the war.

Having “won” the lottery, John reported to Eglin Air Force Base in Florida to learn to operate as a FAC. After completing his training, his next stop was Nha Trang, South Vietnam, where he flew missions primarily in the III Corps area of responsibility in the vicinity of Cam Ranh Bay. He roomed with field surgeons from the 8th Army, who liked having him around because he had his own jeep and could take them to the beach when they had free time. In return, the surgeons let John scrub up and taught him to be a surgical technician in the operating room. The experience helped John land a job years later on the faculty of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health in Baltimore.

During one such surgical assistance session, a badly burned FAC pilot was brought in. John knew the officer from the Air Force Academy, although he was a couple of years ahead of John. His burns were severe and he could not talk, but John spent a lot of time with him, talking to him even though he could not respond. Being too weak to move, the officer could not be evacuated to a hospital better equipped to treat him. Finally, some new burn ointment arrived from Texas and the injured officer improved enough to be transferred stateside. He silently saluted John before he departed, even though John was the junior officer. Miraculously, the injured officer survived the war and John reconnected with him many years later.

During one FAC mission out of Nha Trang, John took a hometown reporter along to see what flying low and slow in search of the enemy was like. During the flight, the reporter noticed a line running up the side of a mountain and pointing north. John flew down to take a closer look, snapping some pictures with a black and white Polaroid camera and reporting what now appeared to be several parallel and lateral open areas on the side of the mountain. A special forces team later reconnoitered the site and discovered it was a North Vietnamese radio antenna, likely used to report on U.S. military activities in the III Corps area. Strike missions were ordered and the antenna was destroyed. The Champaign-Urbana Courier, the News Gazette, and WLRW Radio all covered the story, making sure the people of Tolono knew what their hometown hero was doing in the war.

John was also exposed to Agent Orange during his time as a FAC. During “defoliant” missions, three C-123 twin-engine “Provider” aircraft would fly in a tight formation low over the jungle spraying Agent Orange. John flew above the formation watching for enemy fire, ploughing through the Agent Orange mist floating above the spraying aircraft. John is certain some of his health issues are Agent Orange related.

Around October of 1967, John was reassigned to the Marine fortress at Khe Sanh. The base was under constant attack by the North Vietnamese, who were determined to replicate their 1954 victory over the French by surrounding and defeating the Marines. The Marines, however, held their ground. John flew his Bird Dog from the Khe Sanh airfield, helping detect enemy positions and calling in supporting fires.

During one such mission just before Christmas in 1967, John was called upon to assist two F-4 aircrew shot down near Tchepone Pass, Laos. Armed only with an M14 rifle, a revolver, and smoke rockets, and taking small arms fire from North Vietnamese forces, John held off the enemy and provided cover for one of the downed aircrew as he moved from bomb crater to bomb crater up the side of a mountain. With John flying low overhead in his Cessna Bird Dog, the aviator made it to a point where an unarmed Marine helicopter could rescue him. After refueling in Khe Sanh, John returned to the scene of the F-4 crash to search for the other aviator, all the time taking fire from the North Vietnamese. Unfortunately, the second aviator did not survive the crash. For his bravery under fire and disregard for his own life, John was awarded the Silver Star, our military’s third highest award for valor in combat.

In December of 1967, bad weather around Khe Sanh forced John to land at Nkhon Phanom Air Base in Thailand. He arrived just in time to see the Bob Hope Christmas Show. Even better, because John knew the officer in charge of the Officers Club, he attended a buffet with Bob Hope, Raquel Welch, Barbara McNair, Miss World, and other cast members after the show. This was the second of three times John would meet Bob Hope during his Air Force career.

As the North Vietnamese lay siege to Khe Sahn at the beginning of 1968, the mortar, artillery and rocket attacks intensified and small arms fire increased. John continued to operate from the base, flying FAC missions and watching as B-52s dropped tons of high explosives on the enemy forces hiding in the jungle. When John flew too close to the B-52s’ targets, the shock waves from the bombs buffeted his Cessna through the air.

Despite the incessant bombing and supporting artillery fire from U.S. forces, the North Vietnamese pressed their attack until it became too dangerous for John to operate from Khe Sanh’s airstrip. He was directed to leave, but continued to fly from Khe Sanh for two additional weeks. Finally, he was told that if he enjoyed being an Air Force captain, he needed to get out of Khe Sanh and operate from Da Nang. The Marines defending Khe Sanh displayed their admiration for him when he finally left by designating him as an honorary Marine. They also held on to Khe Sanh until the North Vietnamese siege broke. The Marines pulled out of Khe Sanh in June of 1968 and the base officially closed in July.

John left Vietnam and returned to the United States in the latter half of 1968. He had been designated for the Skylab astronaut program, but his entry into the program was delayed. Instead, he reported to Hurlburt Field on Eglin Air Force base for six months duty as a FAC instructor, helping train pilots to do what he had done so successfully for the past year. At the end of the six months, the Air Force again delayed John’s entry into test pilot school at Edwards Air Force Base in California and continued him as a FAC instructor in Florida. Six months later, the same thing happened. When the Air Force sought to delay him a fourth time, John decided to return to civilian life, having accrued enough time on active duty to do so. Still, he continued to serve in the Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard in Utah, Maryland and Colorado. He retired in 1986 as a Lieutenant Colonel having flown 665 combat missions. He was awarded the Silver Star, two Distinguished Flying Crosses, the Bronze Star, twenty-six Air Medals, and the Vietnam Cross of Gallantry.

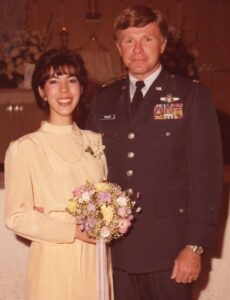

John’s civilian life is every bit as extraordinary as his military career. After the Air Force, he obtained his MBA from the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, graduating in 1972. He spent the next four years on the faculty of Johns Hopkins University before accepting the invitation of a friend to fly for Frontier Airlines, which later merged with Continental Airlines. He formally retired from Continental when he reached the mandatory retirement age of sixty, having amassed nearly 31,000 flying hours. He’s an active member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars and an ardent supporter of U.S. servicemembers. Finally, after his first marriage ended amicably, John married his wife Chris, who has stood by his side now for over thirty-eight years.

No story about John would be complete without mentioning the impact of Scouting on his life. John and his best friend, Lin Warfel, joined Cub Scouts as young boys. Lin’s mother, Adeline, was their Den Mother. Adeline lost her husband on the beaches of Normandy during World War II and was like family to John. John credits Scouting with reinforcing the values his parents taught him, allowing him to be successful in life. John has tried to pay that back to Scouting, working with Boy Scouts and leading trips to exciting places around the United States, helping mold young men into solid citizens. John’s influence worked best at home, though, with three of his sons becoming Eagle Scouts.

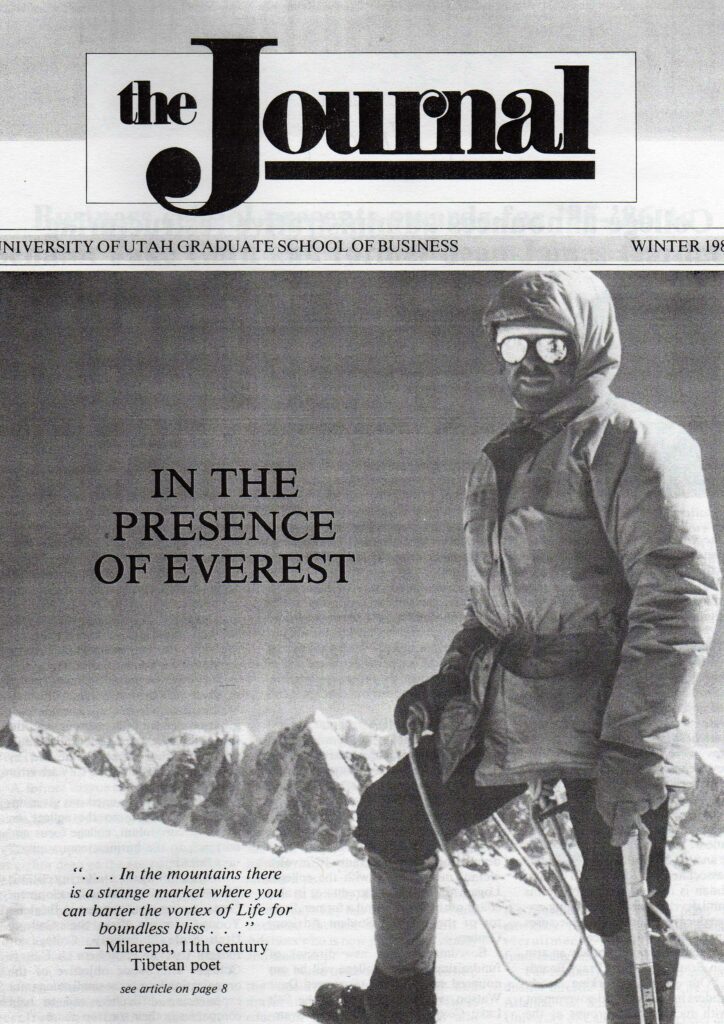

An outgrowth of Scouting is John’s love for the outdoors. He remembers as a boy marveling at the news Sir Edmund Hillary and Tensing Norgay had successfully reached the summit of Mt. Everest in 1953. He climbed to the top of the highest tree in his backyard and thought to himself that someday he, too, would climb that mountain. Never losing sight of his dream, John pioneered an adventure program at Frontier Airlines and, together with other Frontier and Continental Airlines employees, climbed mountains around the world, including in the Alps and the Andes, as well as Mount Fuji in Japan and Mount Kilimanjaro in Africa. Their initial climb was to the summit of Island Peak, also known as Imje Tse, near Mount Everest in the Himalayas. There, without oxygen, John and one other of the eight Frontier Airlines employees on the expedition reached the 20,350 foot summit!

Although it has been a long time since John marched across the Air Force Academy campus, he still has a strong bond with his graduating class. At their fiftieth reunion in 2013, John made sure the program included a tribute to their wives in the Air Force Academy Chapel. John wants everyone to understand the crucial role military spouses play in supporting our armed forces. While servicemembers are deployed around the globe in harm’s way, it’s military spouses who hold their families together amid the reality that they may never see their loved ones again. The 700 people attending the tribute wholeheartedly agreed!

Words will never be enough to thank Lieutenant Colonel Heimburger for his many years of selfless service to the United States. Through his example during times of war and times of peace, he has embodied all that is good about America. He’s taught countless young men and women to see challenges as opportunities rather than barriers, and reinforced that the United States is the land of the free and the home of the brave. Voices to Veterans proudly salutes Lieutenant Colonel Heimburger for all he has done for our country. We wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed John’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

March 17, 2020 @ 12:50 AM

I never new John had such a exciting life. John is a real hero no doubt about it. I have spent many years with John in the vfw and he continues to serve veterans the Boy Scouts his family his beautiful wife and above all his church and God. I’m proud to call Col. John a great and true find. John is also a great speaker.

March 17, 2020 @ 6:52 PM

James – thanks for your feedback on John – he is truly a great American!

March 17, 2020 @ 12:52 AM

I would be interested in such a life exp printed like John but I can’t believe I van do it now.

March 17, 2020 @ 6:53 PM

Thanks James – I’ll reach out to you.

July 1, 2020 @ 3:43 AM

Learned a lot from this, thank you for such a well-written piece!

July 29, 2020 @ 10:41 AM

I’m so glad I found this!!! My dad in Vietnam was a USAF Major (and retired from the Air Force a Lt. Colonel) . He came over from Holloman with the 366th, but he didn’t want to do maintenance, he loved to fly!! So he volunteered for FAC. He loved doing that!! 🙂 He did pretty good, too (of course I’m his daughter so I’m kind of prejudice. LOL) He flew a little Cessna 01 BirdDog. He was there about 1965 to early 1968. (I know because midway through 1968, we were on our way to W Berlin where he became (eventually) Base Ops Officer was at Templehof.

I just wanted to say “Thank you for your Service!!”

Carol (Henry) Edge

July 29, 2020 @ 10:01 PM

Carol, thanks so much for your comment and for your dad’s service, as well!

November 24, 2020 @ 5:17 AM

John is a close friend and neighbor. I too served 24 years in the AF and was a pilot in Continental airlines. My background is nowhere as colorful as John’s. My only claim to fame was as the section commander of the first class of women in Air Force pilot training. I later wrote a lengthy paper while at the Air Command and Staff College titled “An analysis of the training given the first women in UPT”.

July 12, 2024 @ 10:43 PM

how do i find out about my father,Lee Ellis sr US Air Force { Korea } SGT.US Air Force buried @ Lancaster Memorial Park,S.C. 29720 PLEASE contact me with any information on the jobs he held in the USAF,thanks

July 13, 2024 @ 10:26 AM

Lee – You can request your father’s military records from the National Archives through the following website: https://www.archives.gov/veterans/military-service-records.

I hope that helps!

V/r,

Dave Grogan