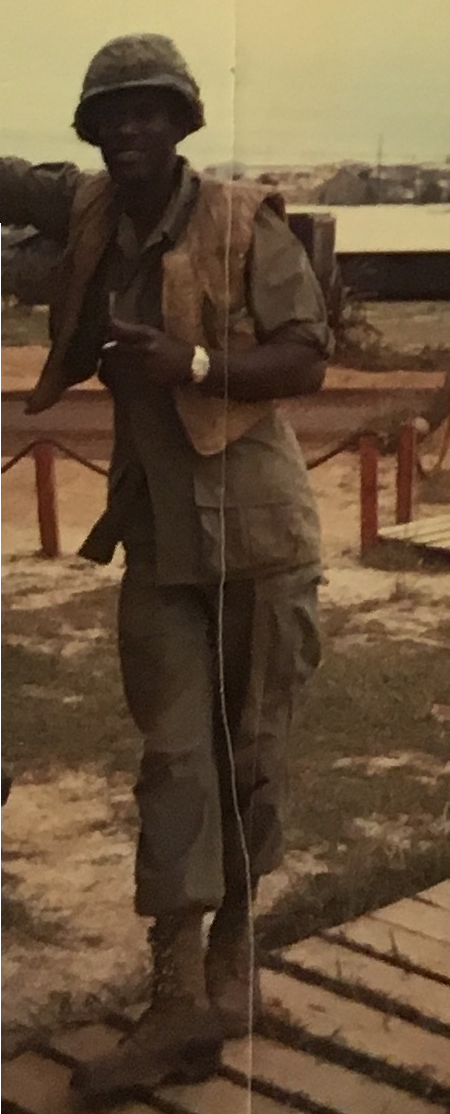

Staff Sergeant Adam Joseph, U.S. Army – Two Tours In Vietnam Says It All

Staff Sergeant Adam Joseph has seen a lot in his life. He’s survived two tours in Vietnam and Hurricane Katrina. He weathered both storms with a strong sense of family, a total commitment to his fellow soldiers, and an unwavering faith in God. I’ve spoken to some of the men he served with and they are inspired by his example. This is his story.

Adam was born and grew up in New Orleans, Louisiana. He was the second oldest in a family of eight sisters and five brothers and the son of a Navy veteran. While his family was very poor, his mother and father instilled in all of them the importance of family and strong moral values. They also taught Adam the value of hard work, and after graduating from George Washington Carver High School in 1965, he began working in a shipyard learning to be a welder. However, because he had just turned eighteen before he graduated, he was soon invited to join the Army by his local draft board.

As a new draftee, Adam reported to the Customs House in the heart of New Orleans around May of 1966 to fill out paperwork and get his Army physical. After saying goodbye to his mother and father, he and the other Army draftees were loaded onto a bus and taken to Basic Training at Fort Polk, Louisiana, about four hours away.

Basic Training lasted eight weeks under the intense Louisiana summer sun, but it didn’t bother Adam because he was used to the heat and humidity having grown up in New Orleans. As a result, he got through the training without much difficulty because he did what he needed to do to get through. Not everyone had the same cooperative attitude. Adam remembers one big guy who had been a top wrestler in high school and was always giving the drill sergeant a hard time. The drill sergeant was a small man, so the recruit thought he could intimidate him into allowing him to slack off. At one point, the recruit outright told the drill sergeant he wasn’t going to do what he’d just been instructed to do. The drill sergeant took off his hat and the recruit took a swing. Moments later the drill sergeant had the recruit begging to let him go. The drill sergeant didn’t hurt the recruit, but he made it clear from that point on, he was not to be messed with—and no one did.

After graduating from Basic Training, Adam headed to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, for Advanced Individual Training (AIT) in artillery. He trained on the 155-millimeter self-propelled howitzer, where he learned to fire the big gun on the ranges in central Oklahoma. After Fort Sill, he returned to Fort Polk for Tiger Land training, which was training specifically tailored to prepare soldiers for combat in Vietnam. Adam spent six weeks at Tiger Land learning how to fight and survive in the jungle. The training included live weapons firing, identifying and avoiding trip wires and booby traps, evading capture, avoiding poisonous snakes, and jungle survival skills. After Tiger Land, Adam returned to Fort Sill for additional training on the 155-millimeter self-propelled howitzers. Once he completed that training, he was off to Vietnam.

In July of 1967, Adam departed for Vietnam from the West Coast together with a plane load of other replacement soldiers. They flew on a chartered jet, complete with stewardesses, to Cam Ranh Bay in the Republic of South Vietnam. After the long trip, the soldiers were happy to get off the plane and were hugging the stewardesses goodbye, but as Adam departed on the tarmac, he saw the caskets of fallen American servicemen waiting to be loaded on an outgoing plane. It was a somber reminder that the Vietnam War was deadly serious.

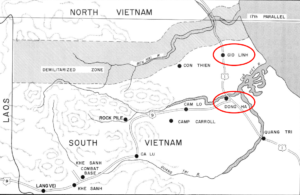

Cam Ranh Bay was a major staging area for new arrivals, so Adam didn’t stay there long. He boarded a C-130 cargo transport aircraft and flew north about two hours to Dong Ha in the vicinity of the demilitarized zone (DMZ) between South and North Vietnam. From there he and two other replacement soldiers boarded a Huey helicopter gunship for the final leg of the trip to his unit at Gio Linh, which is just south of the DMZ on Highway 1. That highway runs all along the Pacific coast of South Vietnam, from the DMZ to Saigon.

Adam’s unit was Charlie Battery of the 1st Battalion of the 40th Field Artillery (1st/40th). The battery consisted of six self-propelled M-108 105-millimeter howitzers, each of which could fire a 33-pound explosive projectile up to seven miles. The men of Charlie Battery were happy to see the three replacements arrive, because it meant three members of the unit whose tours of duty were up could finally go home.

A lesson Adam quickly learned was that everyone in the unit pulled together and looked out for one another. It didn’t matter who you were or where you came from because everyone was in it together. In particular, Adam remembers soldiers making sure those posted on guard duty at night didn’t fall asleep because if they did, the North Vietnamese would infiltrate their position and turn the defensive claymore mines around so that they faced the U.S. firebase rather than facing the North Vietnamese positions. Then, when the enemy attacked the base and the U.S. defenders set off the mines, they would fire shrapnel at U.S. soldiers rather than the attacking enemy.

Adam also relays that the men had various ways of coping with the stress of coming under enemy fire on a daily basis for their entire yearlong tour. He said you just had to learn to deal with it, it was as simple as that. It’s not something you can explain to someone how to do—you just have to do it on your own. Some people turned to alcohol and others to drugs, but everyone had to come to terms with the fact that they might die at any moment. In fact, Adam saw men get killed nearly at the end of their tours when they were looking forward most to going home. The aftermath of the stress stayed with Adam long after he returned from the war.

Adam completed his tour with the 1st/40th in July of 1968. He originally intended on getting out of the Army, but as he was now a sergeant and had made it through Vietnam, he decided to reenlist in return for orders to Germany. The Army was more than willing to oblige, so Adam went home to New Orleans on thirty days leave after departing Vietnam and then reported for duty with the 1st Battalion of the 36th Field Artillery (1st/36th) in Wiesbaden, Germany.

Adam really enjoyed his time in Germany, but surprisingly, in February of 1971, he and several other soldiers from his unit were ordered back to Vietnam. Adam soon found himself in the vicinity of Dong Ha firing 155-millimeter self-propelled howitzers—the same guns he’d previously trained on at Fort Sill. This time, though, his gun took a direct hit from an enemy round. One crewmember was killed, one had a serious stomach wound, and Adam was blown out of the unit and had a portion of his jaw shattered. He woke up on a plane heading to the Army Hospital at Camp Zama in Japan where the surgeons reconstructed his jaw. He also was bleeding out of both ears after the blast and suffered significant hearing loss—a condition that affects him to this day.

Unbelievably, Adam’s injuries were not enough for a ticket home, so he returned to Vietnam after his recuperation at Camp Zama. This time, though, he stayed in the rear and was assigned to work in a supply room. He departed Vietnam for the last time on January 14, 1972. He continued to serve in the Army Reserves until he was finally discharged on September 13, 1976.

As is the case for many combat veterans, Adam found transitioning back to civilian life difficult. Not only did he have to fight racial prejudice—one California bar he visited on his way home from Vietnam served his white buddies but refused to serve him because he was black—but he was also very angry and couldn’t escape his memories of the war. He tried working on a police force for a year and a half, but didn’t like it, so he went back to the shipyard and ultimately to working offshore in the oil fields in the Gulf of Mexico.

In late August 2005, Adam and his family fell victim to Hurricane Katrina. His mother and brother, who lived in the hard-hit 9th Ward, had to be rescued from their roof after the levies gave way to the floodwaters. Adam had three feet of water in his house, but the worst tragedy was that his baby sister, her husband, and her son were lost in the flood. Adam and his wife, Alice, had to rebuild their lives from scratch.

What ultimately got Adam through Katrina and the painful memories of the Vietnam War was he rediscovered his faith in God and returned to the church. Not just any church, but the church that he and all of his brothers and sisters were baptized and married in—Carver Desire Baptist Church in New Orleans. Now Adam sings in the church choir and serves as a Deacon. He is a firm believer in the power of prayer.

As a result of his wartime service in Vietnam and his tours in Germany, Adam earned a Purple Heart, the Vietnam Service Medal, the Vietnam Campaign Medal, the National Defense Service Medal, the Good Conduct Medal, and four overseas service bars.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Staff Sergeant Adam Joseph, U.S. Army, for his distinguished wartime service and his bravery under fire. When our nation called, he willingly went into harm’s way, not once, but twice, to help defend our freedom. Now he continues to serve his community through his church. While we can never repay Adam for the sacrifices he made during the Vietnam War, we can extend to him our most sincere thanks for his dedicated and outstanding service in the U.S. Army. We wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Adam’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.