LCDR Alfred Sokolowski, U.S. Navy – Dreadnoughts to Destroyers: A Two-Ocean Sailor in World War II

Lieutenant Commander Alfred “Ski” Sokolowski, U.S. Navy (Retired), has experienced much over the last ninety-nine years. He had a front row seat in World War II as his ships plowed the North Atlantic, protecting convoys from German submarines. He fought on a destroyer in the Pacific, helping recapture islands lost to Japan at the start of the war, and then joined the fight again just five years later in the Korean War sailing off the coast of North Korea. As if that wasn’t enough, he took on the dangerous job of explosive ordnance disposal and managed weapons logistics in the western Pacific. He didn’t just watch U.S. history from a distance—he lived it over the course of thirty years. This is his story.

Alfred was born to John and Rachel Sokolowski in March 1924 in Jerome, Pennsylvania, a small town in Somerset County, located in the southwestern part of the state. His father had his own coal mine and supplied coal to the local dairy farmers so they could pasteurize their milk before taking it to market. His mother stayed home to take care of the family, no small feat given Alfred was the ninth of ten children. In all, Alfred had eight sisters and one older brother, so his home was a lively place growing up.

Alfred attended school in Jerome through the eighth grade, but began high school at Conemaugh Township High School in nearby Davidsville, Pennsylvania. He had only made it through his freshman year when his father passed away, so his mother moved the family to suburban Chicago to be nearer her relatives. Alfred continued his education in Chicago at Fenger Academy High School, where he completed his sophomore and junior years.

By the early spring of 1941, Alfred was ready to move on. His high school swim coach had done a tour in the Navy and told him if he didn’t know what he wanted to do with his life, joining the Navy was a good way to help him find out. Armed with that advice, Alfred and a friend from high school decided to give the Marines a try. They went to the post office to follow through on their decision, only to learn the Marine recruiter was temporarily unavailable. Committed to their decision, they sat on the cold granite floor to wait. After a while, a Navy chief (E-7) walked up to them and asked what they were doing. When they said they wanted to enlist in the Marines, the chief told them the Marine sergeant wouldn’t be back until later, but they were welcome to talk with him until the sergeant returned.

Soon the Navy chief was telling them about the hot meals and warm bunks they’d have in the Navy but not in the Marines. The chief’s sales pitch, together with the sharp appearance of the Navy’s uniforms, worked their magic on Alfred and he decided to enlist in the Navy for three years. Alfred’s friend could not be swayed. He waited for the Marine recruiting sergeant to return and enlisted in the Marines. The two friends then went their separate ways, heading off to their respective service’s boot camps.

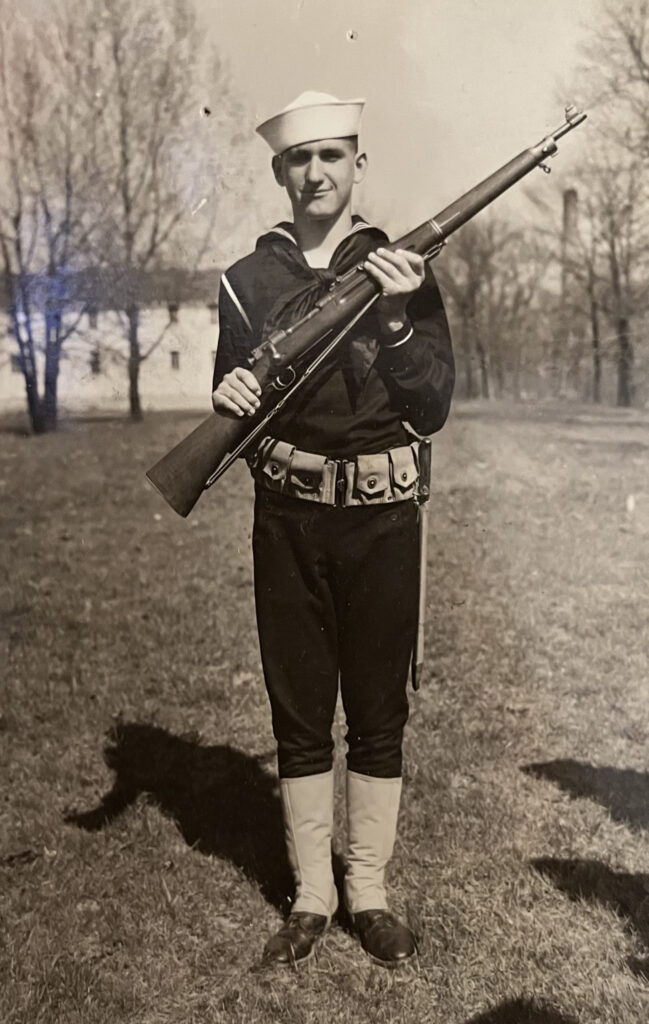

Since the Navy’s boot camp was located at Naval Training Center Great Lakes, just north of Chicago, Alfred did not have far to go. He began his eight weeks of training in April 1941, just after his seventeenth birthday, learning the ins and outs of being a sailor. He did not find boot camp difficult and graduated in the summer of 1941 as a Seaman 2nd Class (E-2) making the lofty sum of $21.00 per month.

After bootcamp, Alfred received orders directing him to report to the USS Arkansas (BB-33), a mammoth battleship (often referred to as a “dreadnought”) commissioned into the Navy in 1912. Five other graduating sailors also received orders to the Arkansas, while six more received orders to USS Texas (BB-35). As both ships were homeported in Newport, Rhode Island, the group of twelve traveled together. When they arrived in Newport, the USS Arkansas was underway, so Alfred and the others bound for that ship stayed aboard USS Texas until Arkansas returned to port.

Life onboard one of the oldest battleships in the U.S. Fleet was much as it had been since the day the ship commissioned. Alfred was initially assigned to help maintain the officers’ stateroom area, which meant constantly polishing the floors and touching up paint. He was also assigned to the ship’s 7th Division, which meant he had to do routine maintenance on the main deck and man the officers’ motorboat, where he served as the bow hooker. Alfred’s most impactful assignment, though, was as a mess cook preparing meals for the 5-inch/51-caliber gun crews assigned to the 7th Division.

The cooking supplies Alfred worked with were basic. In fact, since the Navy did not supply condiments to help spice up the meals, Alfred took it upon himself to purchase condiments for everyone’s use. A First Class Gunner’s Mate (a petty officer (E-6) whose job specialty was maintaining and firing the ship’s guns) noticed Alfred’s extra effort, not only with the condiments, but also with everything else he did, and asked if Alfred would like to “strike” to be a Gunner’s Mate. Alfred asked the petty officer what a career as a Gunner’s Mate entailed and it sounded like something he would enjoy doing, so he said yes.

From that moment on, the First Class Gunner’s Mate took Alfred under his wing. Not only did he teach Alfred how to maintain and fire the Arkansas’ 5-inch/51-caliber broadside guns, but he also taught him about how to be successful in the Navy. He gave him practical advice about what he needed to do as a seaman and leadership advice about how to handle himself once he became a petty officer. He painted a clear picture for Alfred of what he could expect from a career in the Navy and gave him principles to live by. Throughout Alfred’s career, he recalled his time with this First Class Gunner’s Mate and tried to follow the advice and life lessons he had been given. Alfred considers his time with the First Class Gunner’s Mate to be one of the most important experiences of his nearly thirty years in the Navy.

During the summer and fall of 1941, the United States continued its support of England and inched closer to entering World War II on the side of the Allies. In August 1941, USS Arkansas accompanied other U.S. Navy ships escorting President Franklin D. Roosevelt to meet with Prime Minister Winston Churchill off the coast of Newfoundland for the Atlantic Charter Conference, where both countries agreed upon their war aims. The conference was held on the British battleship, HMS Prince of Wales, which Alfred actually had the opportunity to go aboard while the conference was ongoing. After the conference ended, USS Arkansas returned to the United States and later patrolled the mid-Atlantic a couple of times in mid-September. These patrols were dangerous, even though the United States was not yet at war. In October, two destroyers, the USS Kearny (DD-432) and the USS Reuben James (DD-245), were both torpedoed by German submarines in the general vicinity of Iceland. The USS Reuben James sank on October 31 with the loss of 100 members of her crew.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor plunged the United States into World War II. The attack was personal for Alfred, because his high school friend who enlisted with him earlier in the year was killed on board the USS Arizona (BB-39) when the ship blew up after a Japanese armor-piercing bomb penetrated a powder magazine. One week later, Alfred found himself sailing onboard USS Arkansas in the North Atlantic again, heading for Iceland. The ship returned to Boston in late January 1942, then transited to Casco Bay, Maine, for convoy escort training. In March, the ship sailed to Norfolk, Virginia, for an overhaul, and in July, it departed for New York City to begin convoy escort duty as the flagship for Task Force 38.

From August 1942 until Alfred transferred from the ship, USS Arkansas escorted convoys across the Atlantic Ocean to Scotland. One of Alfred’s primary duties during this time was to serve as a lookout on the bridge or high up in the crow’s nest, keeping a watchful eye for German submarines. The job was difficult because the submarines attacked at night and the only indicator that a submarine was in the area might be a periscope sticking out above the water’s surface. Alfred and the other lookouts knew if they saw anything, they had to report it.

Alfred also served as a member of a 5-inch/51-caliber gun crew. These guns were located on the port and starboard sides of the ships, three on each side. To ensure the guns could be manned and fired on short notice, the gun crews lived in the compartments that housed their guns. They maintained a supply of live 5-inch projectiles, and sometimes even powder bags, alongside the guns, so they were always ready to fire. Alfred’s gun was on the ship’s starboard side and took five to six people to fire. He gained lots of experience firing the gun during gunnery practice and eventually promoted to gun captain. This meant he led the team of men firing the gun.

The gun crew’s sleeping arrangements harkened back to the days of sailing ships. Because Alfred was a junior sailor, he slept on a hammock strung between two poles. The senior petty officers were issued cots, which were more comfortable until the ship got into high seas. Then the cots slid back and forth across the deck as the ship rolled, while Alfred and the junior sailors simply swung back and forth, secure in their hammocks.

The sparse living conditions also meant Alfred had little space to store personal items. Everything he owned, including his uniforms, had to be stored in a locker about thirty inches wide, tall, and deep, although he was able to hang his winter peacoat in a locker with the coats of the other sailors. When it came time to wash his uniforms, he filled a bucket with cold water. He then used a steam outlet in the shower to heat the water until it was hot enough to wash his uniforms, which he did in the bucket while sitting on a three-legged wooden stool. Once satisfied his uniforms were clean, he hung them, together with the bucket, in the gun crew’s living spaces to dry.

Alfred wore his enlisted blue uniform most of the time, but he and the other sailors were permitted to wear a t-shirt and dungarees when they were doing hull maintenance over the side of the ship. Hull maintenance involved scraping any barnacles off the ship above the waterline, brushing on a rust inhibitor, and then painting over the area with gray paint. It was dirty work, but Alfred didn’t mind because the dungarees were much more comfortable than his Navy blues.

When it came time for payday, Alfred filled out a pay chit requesting to be paid. He received his monthly pay in cash, although he never took the full amount, instead leaving some in his paymaster savings account. Since his mother needed help and he had nowhere to spend his money, he always sent half his pay home. The rest he kept for those few times when the ship pulled into places like Iceland for a few days ashore.

As the war continued, the Navy started to bring new ships online and it needed experienced sailors to form the backbone of their crews. As a result, Alfred, now a Gunner’s Mate Second Class (E-5), transferred from USS Arkansas at the end of 1942 to a new Fletcher-class destroyer still under construction, the USS Isherwood (DD-520). Before reporting to the ship, he attended a Gunner’s Mate school to learn to fire the 5-inch/38-caliber gun, which would be the main battery on his new ship. He then moved to Staten Island, New York, where the ship was being built, as part of the pre-commissioning crew. Because he could not yet live on the ship, he stayed with an old Italian family who rented him a room. He went to the shipyard every day, working with other Gunner’s Mates to inventory spare parts the ship would need in the event the guns were damaged in combat.

The Isherwood was finally commissioned on April 12, 1943. Throughout April and May 1943, the crew trained on the new ship as far north as Casco Bay, Maine, and as far south as Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. By August, it was ready for escort duty and it sailed with a convoy that included the RMS Queen Mary, which was serving as a troop ship ferrying soldiers to England. The Isherwood was then operationally assigned to the British Home Fleet at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands to help search for the German battleship Tirpitz, the sister ship of the infamous Bismark, which had been sunk earlier in the war.

When Isherwood made a port call in Kirkwall, the capital of the Orkney Islands, Alfred got the opportunity to go ashore. As he was walking back to the ship, he passed a sail loft where a sail maker was sewing sails. Alfred said hello to the man and noticed he had a beautiful copper and brass kerosene powered running light for sale that must have been salvaged from a wrecked ship. Alfred purchased the running light and managed to get it home, and it still decorates his living room to this day, although now it is powered by electricity instead of kerosene.

Alfred and USS Isherwood returned to the United States at the end of September 1943, escorting a convoy to Boston. In November, the ship headed south for the Panama Canal and then north to San Francisco, to begin operations in the Pacific theater. Its first assignment was as part of Task Force 94 in the Aleutians campaign, an oft forgotten aspect of the war fought around Attu and Kiska Islands, the only U.S. soil captured by Japanese forces during World War II. The ship operated out of the U.S. Navy base at Dutch Harbor, Alaska, hunting for Japanese submarines and screening U.S. ships conducting operations in the area.

Although Alfred was used to sailing in the North Atlantic, operations in the northern Pacific took cold to a new level. He describes the water as being so cold, the surface appeared to be more of a slurry than flowing water. The weather was also different, with frequent snow and ice storms. U.S. ships used these storms to their advantage when Japanese planes spotted them and came in for an attack. The ships would make their best speed toward the storms to hide from the attacking planes. If they could not make it into the cloud cover, they stood and fought.

Alfred’s main job on the Isherwood was mount captain for its Number Five turret, which housed the ship’s stern-most 5-inch/38-caliber gun. That meant he was responsible for fighting with that gun, firing at attacking enemy aircraft or surface vessels and bombarding targets ashore. The gun was a powerful weapon, capable of hurling a fifty-four-pound, five-inch diameter shell against surface targets up to ten miles away, and against aircraft targets up to six miles away. In addition to being responsible for firing the gun in combat, Alfred’s team also maintained the gun so it was ready to fire whenever needed.

During the late spring and summer of 1944, the Isherwood provided screening to protect the U.S. ships landing forces on Attu and Kiska islands to retake them from the Japanese. Then, in June 1944, the ship participated in a raid on Japan’s Kurile Islands, attacking shipping in the area and bombarding targets ashore.

Isherwood finally left the frigid waters of the northern Pacific in August 1944, headed for San Francisco and some needed repairs. From there it headed to Pearl Harbor, and finally in October 1944, it joined the assault force in Leyte Gulf for the invasion of the Philippines. Throughout the Philippine operations, Isherwood conducted anti-submarine patrols and provided gunfire support for U.S. Army forces ashore. In late December, the ship joined the landing force in the Lingayen Gulf, where the ship was constantly under attack from enemy planes and kamikazes. The ship’s guns scored numerous hits on enemy aircraft, shooting down at least one kamikaze.

Throughout the Philippine campaign, Alfred and the rest of the crew were at general quarters around the clock, prepared to defend the ship. Despite this, Alfred never felt stressed because he had a job to do where failure was not an option. He also lived better than he did on USS Arkansas in that he now slept in a bunk, not on a hammock, and got to eat in the crew’s mess rather than on tables set up on the mess deck. The food was good and there was always enough, even if it meant just eating a sandwich while Alfred manned his battle station.

After the invasion of the Philippines, USS Isherwood was directed to send one of its two First Class Gunner’s Mates back to the United States to await assignment to new ships under construction. Alfred was one of the two under consideration, but since he was the junior of the two, the other First Class Gunner’s Mate got to make the decision. He decided to send Alfred back while he remained on the ship. Alfred departed as instructed and made his way back to the United States via New Guinea, eventually arriving at Naval Station Treasure Island in San Francisco, where he stayed at the Transient Barracks awaiting new orders.

In early June 1945, a yeoman contacted Alfred and said his previous ship, the Isherwood, had been damaged and was at Treasure Island for repairs. He asked if Alfred would like to return to the ship and Alfred said yes. When Alfred learned what had happened to the ship, though, he was shocked. On April 22, 1945, USS Isherwood was serving as a picket ship off the coast of Okinawa fighting off Japanese kamikaze attacks when one penetrated the ship’s air defenses and crashed into the Number Three gun mount, killing everyone in the vicinity, including the First Class Gunner’s Mate who had elected to stay with the ship and send Alfred back to the states. Fires broke out and one set off a depth charge in a rack at the stern of the ship, blowing a hole in the deck and killing everyone in the Number Two Engine Room, as well as those trying to put out the fire before the depth charge exploded. Over eighty men were killed, wounded, or missing as a result of the attack. Alfred believes had he been onboard fighting the fires around the Number Five gun mount, he would not have survived.

Alfred returned to the Isherwood, but repairs were not completed until after the war with Japan ended, so the ship’s and Alfred’s wars were over. The ship left Treasure Island in October, retraced its steps through the Panama Canal, and arrived in New York City to participate in Navy Day on October 27, 1945. As part of the celebration, over 1,000 warplanes and forty-seven warships, including the battleship USS Missouri (BB-63), on which the Japanese surrendered just the month before, and USS Isherwood, saluted President Harry S. Truman as he sailed by the line of ships on the USS Renshaw (DD-499). Alfred recalls being awed by seeing the New York City skyline from the deck of his ship.

After Navy Day, the Isherwood sailed to Charleston, South Carolina, for decommissioning. Alfred, now a Chief Gunner’s Mate (E-7), stayed with the ship to ready the ship’s five 5-inch/38-caliber guns for mothballing as the ship prepared to enter the Atlantic Reserve Fleet. USS Isherwood was formally decommissioned on February 1, 1946.

With the war over and the ship decommissioned, Alfred served briefly on the aircraft carrier USS Wasp (CV-18) and the battleship USS Washington (BB-56) as part of their decommissioning crews. Both ships had storied records in the Pacific War, but now that the war was over, their services were no longer required. As he had done on the Isherwood, Alfred prepared each ship’s five 5-inch/38-caliber guns for mothballing before the ships entered the Atlantic Reserve Fleet. USS Wasp was decommissioned on February 17, 1947, while USS Washington was decommissioned on June 27, 1947.

With his decommissioning work complete, Alfred reported to the destroyer USS Turner (DD-834), homeported in San Diego. In 1948, he sailed with the ship to the western Pacific and to various ports in China, where the ship facilitated the transportation of people from Mao Tse Tung’s communist Mainland China to Chiang Kai-Shek’s democratic Formosa. The Turner, and other U.S. Navy forces patrolling the Taiwan Strait, helped deter Mao from further extending his communist regime to the island of Formosa.

After his assignment on the Turner, Alfred returned to Naval Training Center, Great Lakes. This time, instead of being in a company of new recruits, he led one. While there, he was playing basketball with a lieutenant who told him that the Bureau of Naval Personnel was looking for Chief Gunner’s Mates to instruct at three Navy ROTC units: the University of North Carolina, Tufts University, and Harvard University. Alfred said he would do it, indicating the other two chiefs could pick their schools and he would take whatever was left. Thus began Alfred’s three-year assignment at Harvard University, which gave him the opportunity to finish his fourth year of high school and earn his high school diploma.

Once he completed his tour at Harvard, it was time for Alfred to get involved in his second war. He did this aboard the fleet oiler USS Kaskaskia (AO-27), which had a 5-inch/38-caliber deck gun mounted on its stern and thus needed the services of an experienced Chief Gunner’s Mate. The Kaskaskia refueled U.S. ships operating off the coast of North Korea, including ships engaged in fire support missions, which brought her in closer to the coast. She also refueled aircraft carriers launching bombing missions against enemy targets in North Korea, so she played a vital role in the Korean War effort. Alfred, who also served as the ship’s Chief Master-at-Arms, stayed onboard Kaskaskia after the war ended and promoted to Warrant Officer (W-1) while onboard. His promotion provided hope to his fellow Kaskaskia chiefs (E-7s), signaling they, too, could become officers if they wanted to do so.

After USS Kaskaskia, Alfred reported to the Reserve Fleet in Philadelphia to help oversee the ongoing efforts to maintain the many ships mothballed at the end of World War II and the Korean War. Soon after arriving, he ran into another warrant officer who told him he needed to get out of the Reserve Fleet because it was a dead-end job and that instead, he should apply to Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) school. He warned Alfred to do it right away because he would soon be too old to be considered.

Alfred heeded his friend’s advice and went to speak with his commanding officer. Instead of giving him permission to transfer, the captain threw him out of the office and told him to go do what he had been brought there to do. The captain didn’t care Alfred would soon be too old to attend EOD school and that this would be his only opportunity. Alfred did as instructed, but a little while later, the Chief of Naval Personnel paid a visit to Bayonne, New Jersey, and Alfred ran into a fellow warrant officer accompanying the admiral on the visit. Alfred told him what had happened and that he really wanted to go to EOD school. The warrant officer said he would mention it to the Chief of Naval Personnel and they parted company. Three weeks later, Alfred had orders to EOD school, much to the chagrin of his commanding officer.

Thus began what amounted to Alfred’s second Navy career as an EOD officer. Among other tours, Alfred served as Commanding Officer, EOD Unit TWO in Charleston, South Carolina; worked at the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hawaii, the Naval Ordnance Facility in Yokosuka, Japan, and the Naval Ammunition Depot at Seal Beach in California; and served on the staffs of Commander, Task Force (CTF) 73 and Commander, Naval Forces Japan in Yokosuka, Japan. Although Alfred initially entered the EOD world as a warrant officer, the Navy decided to phase out the warrant officer rank in 1959, so Alfred became a lieutenant (O-3) limited duty officer, which recognized his technical expertise as a former Gunner’s Mate and most recently as a trained EOD technician. Alfred subsequently promoted to lieutenant commander (O-4).

An experience Alfred had shortly after reporting to the Naval Ammunition Depot in Hawaii illustrates just how dangerous his new career path was. As a destroyer escort (DE) sailed through the channel on its way out of Pearl Harbor to practice with its depth charges, a Gunner’s Mate onboard accidentally energized the primer on a depth charge and fired a live depth charge with 300 pounds of explosives into the channel. The depth charge was set to go off when it reached a specified depth, but because the channel was not that deep, it did not detonate. As a result, all shipping traffic into and out of Pearl Harbor had to be shut down until the depth charge could be found, brought back to the surface, and disarmed.

Every available EOD sailor got the call to help find the depth charge, including Alfred. He and the others donned their wet suits, went out in the channel in a Mike boat, and dove into the murky waters in search of the lost explosive. To help cover the channel bottom more effectively, the swimmers searched in groups of two or three, holding hands as they methodically skimmed the bottom. Much to his surprise, Alfred and the swimmer he was linked to found the depth charge sitting on its end. Alfred signaled to the other diver to go to the surface and announce the find, while Alfred stayed with the live depth charge at the bottom of the channel. Eventually, additional divers arrived and they returned the depth charge to the surface, where it was disarmed.

Alfred’s subsequent tour with CTF-73 in Sasebo, Japan, was significant because that is where he met Keiko, his wife of fifty-four years. They were married in 1964, making Alfred’s tour with CTF-73 one of his favorites during his Navy career. The tour itself was challenging, though, because he was responsible for managing the moves of classified ordnance around the U.S. Seventh Fleet’s area of responsibility in the western Pacific. His tour with Commander, Naval Forces Japan proved similarly stressful in 1968 when the North Koreans seized the USS Pueblo (AGER-2) and the command played a major role in dealing with the incident. After his tour with Commander, Naval Forces Japan, Alfred retired from the Navy in November 1970, having served almost thirty years on active duty.

With his long Navy career behind him, Alfred bought a boat and he and Keiko settled down in Snohomish, Washington. His intention was to enjoy his retirement by getting away on his boat and doing some fishing, but he ended getting far more than he bargained for. When he was working on his boat one day, a man walked over to him and offered to partner with him in the fishing business. They bought a boat together and fished salmon each spring off the coast of Alaska and in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. When it came time to retire for good, Alfred sold his boat and moved to Sun City West, Arizona, where he and Keiko built a home. Alfred also joined the Mary Ellen Piotrowski Post 94 of the American Legion, continuing his strong ties to the military.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Lieutenant Commander Alfred “Ski” Sokolowski, U.S. Navy (Retired), for his many years of service to our country. In both wartime and peace, Alfred stood the watch, protecting our shores and defending our allies from those who would do us harm. He represents the best America has to offer, displaying courage in battle and a commitment to service. We sincerely thank him for all he has done and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Alfred’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.