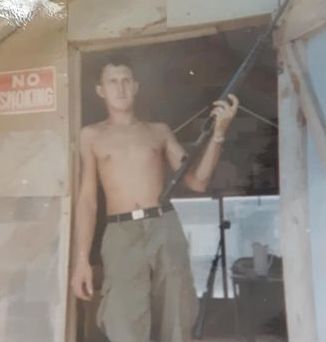

Sergeant Kenny L. Esmond, U.S. Army – Vietnam: Not Scared, Not There

There’s nothing like growing up in a small town. Close-knit families and neighborhoods, safety and security from the hustle and bustle of the city, and the freedom to roam and explore without fear. Sergeant Kenny L. Esmond grew up in such an environment, rarely venturing beyond his familiar Wisconsin surroundings. Yet even a trip to nearby big cities like Milwaukee or Chicago paled in comparison to what the U.S. Army had in store for him, shipping him off at just twenty-one to far off outposts in South Vietnam in the middle of a raging war. Although he returned to his small town after the war, his life was forever changed. This is his story.

Kenny was born in 1949 and grew up in Genoa City, Wisconsin, a small village just north of Wisconsin’s border with Illinois. At the time, the village had about 1,000 residents, so life there epitomized life in every small town in America. Kenny’s father, a World War II veteran, had a great job as a die caster for the Electric Autolight company in Woodstock, Illinois, making parts for cars like the famous hood ornament for the Ford Mustang. Kenny’s mother was a full-time stay-at-home mom, bearing the primary responsibility for raising Kenny and his younger sister. Kenny fondly remembers being allowed to play outside with all the other kids in the neighborhood, with his mother’s only instructions being to be home by 5:00 p.m. on school nights and by the time the streetlights came on in the summer. For a kid, it was small town living at its best.

High school was not as fun. Kenny did not enjoy his classwork at all—so much so that one day he walked out the door of Badger High School in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, and decided not to go back. Once out the door, he wasn’t sure what he was going to do. He didn’t have a driver’s license or a car—all he knew was anything had to be better than wasting his time in school. An opportunity arose when an older cousin told him a factory in nearby Richmond, Illinois, was hiring. Kenny applied, stating on the application he was eighteen, despite being not quite seventeen at the time. Much to Kenny’s surprise, he got the job and started working as a die caster, just like his father.

Kenny was a hard worker, so he did well at the factory. After a little over a year, though, he started having regrets for having quit high school. Still without a driver’s license, Kenny enlisted a friend to take him to Badger High School and he made his way to the principal’s office. The principal was surprised to see Kenny and even more surprised when Kenny asked if he could come back to school to earn his diploma. The principal told Kenny it would take three years, or two years if he worked really hard. Kenny replied he was already eighteen, so the two-year option was his only real choice. Kenny went on to graduate from Badger High School on June 6, 1969, exactly one month after his twentieth birthday.

At the end of 1969, the inevitable happened—Kenny was drafted. He reported to the Military Entrance Processing Station in Milwaukee, together with all the other local draftees. He was given a physical exam, signed some paperwork, and was sworn-in on active duty. From there, he and the other draftees destined for the Army boarded a plane enroute to Basic Training, or “boot camp”, at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. Although they arrived in early December, their formal Basic Training was not scheduled to begin until the full complement of draftees reported in January. In the interim, they trained informally for the two or three weeks preceding the holidays. They were even permitted to take leave and go home for Christmas. Once they returned, the Army’s intense eight-week Basic Training program began.

Kenny liked boot camp because of the way the Army transformed his group of undisciplined draftees from around the country into a cohesive platoon of soldiers. The reason behind the transformation was Drill Sergeant West. Built like a fireplug and a veteran of the war in Vietnam, he wasn’t someone to mess with. Kenny considered him tough but fair, and he inspired Kenny’s platoon to excel. One memory that stands out for Kenny was standing in the front row during weapons inspections. When Drill Sergeant West walked down the row, each trainee presented their weapon to the sergeant, who would inspect it and throw it back to the recruit. Kenny said Sergeant West always gave him a little signal, like a slight nod or wink before he threw the weapon back so Kenny would be prepared to catch it. As a direct result of Drill Sergeant West’s leadership and example, Kenny’s platoon was selected as the Honor Platoon for the Basic Training graduation parade.

After completing Basic Training, Kenny wanted to attend “Jump School” to become an Army paratrooper. He instead received orders to attend supply clerk and warehouse management school at Fort Polk, Louisiana—the same place his father had trained during World War II. Kenny completed his training in April 1970 and received orders to report for duty in the Republic of South Vietnam. His orders did not assign him to a specific unit. Because he was a replacement soldier, he would not learn his specific assignment until he arrived in Vietnam. So, without knowing what the future had in store for him, Kenny took eighteen days of leave at home in Genoa City before reporting to the Oakland Army Terminal in California to wait for a flight to take him off to war.

Once at the Oakland Army Terminal, now Private Kenny Esmond had to wait along with all the other soldiers for their names to appear on a roster indicating they had been manifested on a particular flight. When Kenny and the other men on his flight heard their names called, they picked up their gear and marched to a big metal building where they were locked down until it was time to board. The building remained lit twenty-four hours a day so the men could be closely monitored in case anyone attempted to leave. Other than calling home on the building’s phones to say goodbye to loved ones, there was nothing to do but wait.

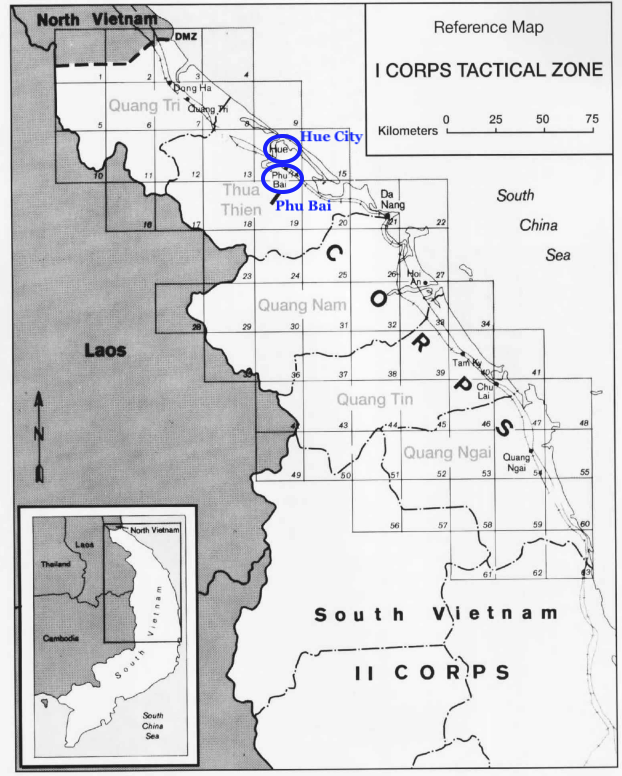

Once Kenny finally boarded his flight, he began the twenty-two-hour trek to South Vietnam. The plane made several refueling stops along the way, including Hawaii, Wake Island, and Japan, before it finally arrived in Vietnam on May 12, 1970. Kenny was initially assigned to the Headquarters Company of the 101st Airborne Division and was transferred to Camp Evans for training. At Camp Evans, which was located sixteen miles northwest of Hue City—the scene of intense fighting during the 1968 Tet Offensive and a North Vietnamese massacre of thousands of South Vietnamese civilians—Kenny learned to conduct jungle patrols, do river crossings, and defend positions in this new, hostile environment.

After almost two weeks of jungle school, Kenny reported to his permanent assignment at the U.S. base at Phu Bai, located eight miles southeast of Hue City on Highway 1, a coastal highway that ran the entire length of South Vietnam. Kenny was assigned to the 1st Battalion of the 502nd Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. When he reported to his sergeant, the sergeant asked Kenny what he knew how to do. Kenny told him his military occupational specialty, or “MOS”, was supply clerk and warehouse management. The sergeant said he wanted Kenny to work in the battalion ammo dump, but he didn’t need people there now. In the interim, he sent Kenny to Fire Base Bastogne—named after the famed defense of the City of Bastogne, France, by the 101st Airborne Division during the Battle of the Bulge—to serve as part of the defensive force protecting the artillery batteries operating there.

Fire Base Bastogne was located about twenty miles southwest of Hue City and was home to several artillery batteries firing 105-millimeter, 155-millimeter, and 8-inch shells. Kenny’s job was to man the base’s defensive bunkers and repair any damaged concertina wire strung around the base to protect it from enemy attacks. One reason for the frequent repairs to the concertina wire was the nightly “mad minutes”, when the base defenders opened up with all their weapons, firing into the dark all around the base to interrupt the enemy in the event they were assembling for an attack or trying to infiltrate the base perimeter. While the mad minutes were effective in disrupting any would be North Vietnamese attackers, they also often damaged the concertina wire defenses, so Kenny and others had to check and make repairs to the wire every day.

After a brief stint at Fire Base Bastogne, Kenny returned to Phu Bai where he continued on bunker and repair duty. Defensive bunkers were built at intervals around the entire perimeter of the base. Each bunker was about eight feet square with sandbag walls and a plywood and sandbag roof. The bunkers had an opening in the front facing the perimeter and an opening in the back allowing entry and exit while shielded from enemy fire. During the day, the bunkers were manned by a single soldier. At night, four soldiers stood guard at each bunker, two outside in fighting positions while the other two slept inside in two-hour shifts. Kenny had nighttime guard duty every other night, while during the day he worked his other military responsibilities.

On Kenny’s first night of guard duty at a bunker on the perimeter of Phu Bai, he was manning an M60 machine gun in a fighting position in front of the bunker when he heard a sound he recognized from his training at Camp Evans. It was the sound of rocket-propelled grenades (“RPGs”) being launched from somewhere out in the darkness. It was common knowledge the Viet Cong (“VC”) in the area knew the layout of the base’s perimeter defenses, so Kenny was sure they knew where he was. The first RPG hit behind the line of bunkers about one hundred yards to Kenny’s left. Sparks flew thirty-five to forty feet into the pitch-black night. A second RPG passed directly over Kenny’s head, again landing behind the bunkers. The enemy continued to launch RPGs, walking them down the line of bunkers, each manned by young defenders like Kenny. Knowing what the results of a direct hit by an RPG would mean, Kenny was terrified. He describes his fear in simple terms: “If you weren’t scared, you weren’t there.”

On another evening when he was standing bunker guard duty, he heard small arms fire further down the bunker line. The word came over the radio that the VC were probing the perimeter and that each bunker team needed to send one man to the area to assist in repulsing the attack. Kenny drew the short straw and started running down the line of bunkers toward the engagement. He was not completely out in the open in that outside the line of bunkers and firing positions, a dirt berm had been constructed to provide cover for those occupying the defensive perimeter. Still, as Kenny ran toward the sound of the gunfire, he remembers praying—not that he would live—but that Jesus would accept his soul. By the time Kenny arrived, the gunfire had subsided and the attack had been repulsed, but it had been a harrowing few minutes. To this day, whenever Kenny hears fireworks on the Fourth of July, it takes him back to Phu Bai, running along the base perimeter alone at night, not knowing what was waiting for him or if he would survive.

The North Vietnamese and the VC weren’t the only ones attacking the bunkers. One night when Kenny and three other soldiers were standing guard in a bunker on the perimeter of Fire Base Bastogne, a King Cobra slithered into the bunker while the men were inside. Kenny described the ensuing melee like a scene from the Three Stooges as they all scrambled to get out of the bunker. When everyone was clear, one of the soldiers killed the invader with his M16, prompting a radio call from the officer-of-the-day asking what was going on. When they told him about the King Cobra, the officer-of-the-day told them they should have killed it with a stick. That was one piece of advice they had no intention of following.

Because Kenny was a supply clerk, his daytime duties at Phu Bai initially involved managing the supply records for the uniform inventory in support of the Property Book Officer. After two months, though, he was so bored that he went to the Property Book Officer and said he needed to do something else. Appreciating the initiative, the Property Book Officer sent Kenny across the street to the battalion ammunition (“ammo”) dump to talk to the sergeant in charge. When the sergeant heard Kenny wanted to work in the ammo dump, which supplied small arms ammunition to infantry companies in and around Phu Bai, the sergeant just shook his head and told Kenny to come in and get started.

Kenny’s duties working at the ammo dump were wide and varied. When the inventory of M-16 and 40-caliber ammunition and cratering charges grew low, he would requisition more and ride in a two-and-a-half ton (“deuce and a half”) truck to the main ammo dump on the other side of Phu Bai to pick it up. These trips were dangerous enough because Kenny was riding in a truck filled with ammunition, but on at least one occasion he was fired upon as he passed through a hamlet on this way to pick up the load.

As time passed and Kenny became familiar with all the ammo dump’s procedures, both the sergeants who were senior to him “went back to the world”, which meant they returned to the United States. This provided an opportunity for Kenny because he was promoted to sergeant and took over the ammo dump after the two sergeants left.

Once Kenny was in charge, one of his new responsibilities was to travel to the surrounding fire bases to restock their ammunition inventory. To tackle this mission, Kenny heloed out to the fire base, inventoried the ammunition on hand, and radioed back an order to bring the fire base’s ammunition back up to its base load. The next day, a helicopter would fly in with the ammunition. Kenny and other soldiers would unload the ammunition onto an open flatbed vehicle known as a “mule” and drive it to the fire base bunkers to restock their supplies. Kenny would then hitch a ride back to Phu Bai on a logistics helicopter later in the day. Similarly, if units were heading home to the United States as part of the U.S. troop drawdown, Kenny would visit the unit, collect its ammunition, and return it to the battalion ammo dump.

As Kenny neared the end of this one-year tour in Vietnam, he decided to extend in country for two more months to figure out his future. On one hand, he was now a sergeant and had done very well, even having been awarded an Army Commendation Medal for his outstanding work and dedication to duty. That made a career in the Army a real option. On the other hand, he wanted to get home to his family and didn’t want a follow-on assignment in Germany, which was a real possibility. In the end, his family and Genoa City won out. Kenny departed South Vietnam on July 6, 1971. Upon his return to the states, he was honorably discharged at Fort Lewis, Washington. He then went back to Genoa City to pick up life where he had left off.

Once he got back, though, he felt like nobody cared what he had done. Even more hurtful, he felt like people avoided him because he had served in Vietnam. Although he was immensely proud of his wartime service, it wasn’t until a fellow Vietnam veteran shook his hand and told him “Welcome home, brother,” at a Memorial Day ceremony forty years later that he started to feel like he belonged again. At the ceremony, Kenny participated in a talking circle, where every veteran attending was given the microphone and an opportunity to talk. After Kenny spoke, the other veterans hugged him, letting him know his service was valued. The event finally let Kenny reconcile how his service in Vietnam had influenced his life.

Kenny is retired now, having worked in construction ever since his return from Vietnam. He is happily married to Kathy, his wife of thirty years, and living in Genoa City. He’s once again enjoying the benefits of living in small town America, just as he did as a kid.

In addition to the Army Commendation Medal, Kenny was awarded the Combat Infantryman Badge and the Bronze Star for his outstanding service in Vietnam. He also wanted to be sure the following special message was included in his story: “To all my sisters and brothers who served in the military—Ooorah!”

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Sergeant Kenny L. Esmond, U.S. Army, for his willingness to serve our country during time of war. At just twenty-one years old, he put his life on the line in far off South Vietnam because he believed in our nation and our democracy. We thank him for his dedication to duty and committed service, and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Kenny’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.