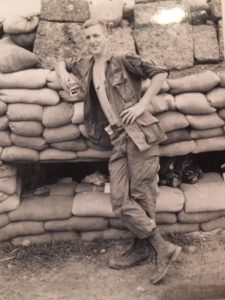

First Sergeant Mike Allen, U.S. Army (Retired)

Some people are called to serve our country in extraordinary ways, putting their life on the line for mission and comrade during time of war. Such is the case for First Sergeant Mike Allen, who served in the Army for twenty-three years, including during the Vietnam War. This is his story.

Some people are called to serve our country in extraordinary ways, putting their life on the line for mission and comrade during time of war. Such is the case for First Sergeant Mike Allen, who served in the Army for twenty-three years, including during the Vietnam War. This is his story.

Mike was born in 1947 and raised in the small farming community of Tuscola, Illinois. He graduated from Tuscola High School in 1965 at the age of seventeen, but couldn’t find a job because he would be subject to the draft on his eighteenth birthday. Rather than wait for the draft, Mike decided to join the Army. His father, a Combat Engineer in Europe during World War II, advised Mike to think about it before making his decision. When Mike assured him he wanted to join, his father signed the necessary parental consent paperwork and Mike enlisted.

Mike reported to Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri for Basic Training in September 1965. He survived the drill sergeants screaming in his face, the early morning awakenings, and the rigorous physical training, and appreciated the camaraderie that developed among the recruits. As would be the case throughout his Army career, if a recruit lagged or needed help, Mike and the others pulled together to make sure their fellow recruit succeeded.

After eight weeks of Basic Training, Mike reported to Fort Polk, Louisiana, for advanced infantry training (AIT). Just as at boot camp, drill sergeants dictated his every move, including improving his proficiency with the M-14 rifle. After concluding the eight-week AIT course, it was time for the new soldiers to find out their assignments. The First Sergeant put the new soldiers in formation and produced a scroll. He yelled out, “If I call your name, stand over at the right. You will not be going to Vietnam.” He then called out one name, which was a foreign sounding name. Because the individual was not yet a U.S. citizen, he would not be going to Vietnam. Everyone else, including Mike, would be.

Mike landed at Tan Son Nhut Air Base in South Vietnam in May of 1966, just as the Vietnam War was intensifying. He was issued orders to the 1st Cavalry Division. The unit had suffered heavy casualties in the first battle of the Ia Drang Valley in November 1965. The battle, which pitted new airmobile U.S. Army helicopter assault forces against North Vietnamese regular soldiers for the first time, was subsequently made famous by the bestselling book We Were Soldiers Once . . . And Young, by the U.S. battlefield commander, Lieutenant Colonel Hal Moore, and reporter Joseph Galloway. In 2002, the book was released as a movie, We Were Soldiers, with Mel Gibson starring as Lieutenant Colonel Hal Moore.

On May 8, 1966, Mike was sent to An Khe in the jungle and rolling hills of South Vietnam’s Central Highlands. The nearest city to the operating base was Pleiku. He joined Alpha Company of the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, 1st Cavalry Division. His company’s mission was to conduct search and destroy missions, where they would go into the field to locate and kill the enemy.

Mike was assigned to be a radio operator, replacing a soldier who had been killed during the first battle of Ia Drang. His First Sergeant said, “Allen, you look like a healthy young man. You’ll be our radio operator.” Mike learned the reason his strength was important was because he had to carry his regular gear plus the radio, giving him a much heavier load than many other soldiers. When Mike said he didn’t know how to operate a radio, his First Sergeant said, “We’ll teach you. Now put this on and get going.” It was on the job training from that point on.

Mike was assigned to be a radio operator, replacing a soldier who had been killed during the first battle of Ia Drang. His First Sergeant said, “Allen, you look like a healthy young man. You’ll be our radio operator.” Mike learned the reason his strength was important was because he had to carry his regular gear plus the radio, giving him a much heavier load than many other soldiers. When Mike said he didn’t know how to operate a radio, his First Sergeant said, “We’ll teach you. Now put this on and get going.” It was on the job training from that point on.

Mike remembers the fear that set in on every mission. He never knew what lurked behind the next tree. On his first mission, when it came time to disembark the helicopter, the veteran soldiers all jumped out and disappeared in the tall elephant grass. The crew chief told Mike to jump, too. Mike looked down and was terrified, so he turned to the crew chief and said he wasn’t jumping. The crew chief told him to look down one more time, and when Mike did, he gave Mike a shove with his boot and Mike launched out of the chopper, landing on the ground. Mike jumped out of helicopters on his own from that point on.

Mike’s unit would normally spend three weeks in the field, then it would be pulled off the line to guard an artillery battery for two weeks, and then the rotation would start over again. If the unit was really deserving, it would get to spend time at the base camp in An Khe.

One junior officer Mike remembers in particular was the unit’s forward observer, who called in precision artillery and close air support strikes during their search and destroy missions. The observer had a habit of taking off his helmet when he started to call in artillery. He’d radio in the target coordinates and then the rounds would come in and hit the designated point. He’d radio again, adjusting fires to drop the next rounds closer to the unit. He’d repeat the process until he put on his helmet and took cover. When the men saw this, they knew the rounds would be coming in very close, so they’d hit their foxholes to avoid being struck by friendly fire.

The most significant engagement of Mike’s tour occurred on August 8, 1966. Mike’s company (Alpha Company), which at the time had about eighty-five men, was on a search and destroy mission in the Ia Drang Valley. Mike’s unit saw the telltale signs of a significant enemy force in the vicinity (markings on trees and recently abandoned camps), but when his unit reported to headquarters that they thought something big was in the vicinity, headquarters replied that, according to intelligence reports, there were no significant enemy forces nearby.

The most significant engagement of Mike’s tour occurred on August 8, 1966. Mike’s company (Alpha Company), which at the time had about eighty-five men, was on a search and destroy mission in the Ia Drang Valley. Mike’s unit saw the telltale signs of a significant enemy force in the vicinity (markings on trees and recently abandoned camps), but when his unit reported to headquarters that they thought something big was in the vicinity, headquarters replied that, according to intelligence reports, there were no significant enemy forces nearby.

Mike’s unit found out headquarters was wrong when it was attacked by an entire North Vietnamese regiment consisting of approximately 1200 men. The North Vietnamese repeatedly charged Alpha Company. The unit took heavy casualties, but the men kept fighting even when wounded. Just as the North Vietnamese were preparing for the final assault to overrun Alpha Company, the sound of approaching helicopters caused the North Vietnamese to abandon the attack and Mike survived. When Mike left the battlefield, he had only five rounds of ammunition left.

During the course of that engagement, Mike recalls an Air Force pilot flying overhead indicated he was returning from a mission and had some ammunition left. He asked Mike’s unit if he could help and they said yes. The pilot keyed his microphone so he was continuously transmitting as he made a strafing run on the enemy, all the time whistling the Air Force song Wild Blue Yonder. He did a second strafing run, again whistling Wild Blue Yonder over the radio. Finally out of ammunition, the pilot wished Mike’s unit good luck and said he’d drink a beer for them when he returned to his airbase.

Mike stated that when the Medevac helicopters arrived, there was only room for the wounded to be evacuated. One soldier, who everyone looked out for because he was mentally slow, asked if he could leave with the Medevac helicopters. Mike said no, that he had to be wounded to evacuate. The soldier asked, “If I’m wounded, would I get to leave on a helicopter?” Mike said yes. The soldier then turned around and showed Mike two bullet holes in his back. Mike immediately tried to assist the soldier to a helicopter, but the soldier walked there under his own power and flew away, waving to Mike as he departed. Mike was also wounded by shrapnel during the battle, which he suspects came from a grenade.

After the battle, a reporter interviewed Mike and the story ran nationwide on August 9, 1966. Mike said the interview was how his parents learned he was okay, since the Red Cross had notified his parents he was wounded but not told them what his condition was or if he was even alive. Quoting from Mike’s hometown newspaper, the Tuscola Review, Mike “was awarded the Purple Heart and Army Commendation Medal for his efforts on August 8, 1966, which included crawling twice through heavy fire and exploding grenades to deliver messages to the forward observer. Because of his action, communications were kept open and reinforcements were brought in.” After recovering from his wounds, Mike returned to his unit and finished his tour of duty in Vietnam.

Mike left Vietnam in May of 1967 and returned on leave to Tuscola, where his town welcomed him home as a hero. One example is when Mike’s Dad asked him to go to a bar. Walking in, Mike saw a local judge with a police chief. Mike’s Dad ordered a beer, while Mike, who was only nineteen, ordered a Coke. The bartender set the Coke on the bar, but before Mike could reach it, the judge stepped up and grabbed it. He asked Mike, “didn’t you just come back from Vietnam?” When Mike said yes, the judge continued, “well, you didn’t drink just Coke in Vietnam, did you?” When Mike said no, the judge told the bartender to “give this man a beer.” The police chief told the bartender “and when he finishes that one, the second one is on me.”

Mike credits the support of his town, and especially the support of his close-knit family, with helping him transition from Vietnam. His father and four of his father’s brothers served in World War II, so they related to Mike because they understood what he had been through. Mike’s father, in particular, helped him learn to talk about his experience, rather than trying to keep it to himself. Mike also had four cousins who fought in Vietnam, so they were able to share their experiences together. Talking about Vietnam made all the difference in the world, as Mike felt like the weight of the world had been lifted from his shoulders.

Mike credits the support of his town, and especially the support of his close-knit family, with helping him transition from Vietnam. His father and four of his father’s brothers served in World War II, so they related to Mike because they understood what he had been through. Mike’s father, in particular, helped him learn to talk about his experience, rather than trying to keep it to himself. Mike also had four cousins who fought in Vietnam, so they were able to share their experiences together. Talking about Vietnam made all the difference in the world, as Mike felt like the weight of the world had been lifted from his shoulders.

After Vietnam, Mike was sent to Germany to serve out the remainder of his enlistment. With the Cold War in full swing, Mike’s job was to patrol the border between Germany and Czechoslovakia. While he was there, his First Sergeant took him under his wing and talked to him about reenlisting. The offer of a $6000 reenlistment bonus and thirty days leave in Tuscola was just too much to pass up. That six-year reenlistment turned into a distinguished twenty-three-year Army career.

Mike retired from the Army as a First Sergeant in 1988. He’s since retired two more times, first from a magnet factory in Kentucky and later from the City of Radcliffe, Kentucky. Mike is now fully retired and living with his wife, Martha, in Winter Haven, Florida. He hopes to relocate soon to his beloved town of Tuscola so he can be closer to family and friends.

Voices To Veterans is proud to salute First Sergeant Mike Allen, U.S. Army (Ret.), for his long career of dedicated service to our country in the Army, and especially for his courage and devotion to duty during the Vietnam War. Mike and his family have answered the call whenever our nation was in need, and for that we are forever grateful.

If you enjoyed Mike’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

March 29, 2019 @ 3:50 PM

I would like to speak to Mike about Pfc Charles R Greene who died 8 of August 1966 in the Ia Drang Valley with A company 7th Can. Charlie and I were 17 when we joined up and went thru basic at Fort Dix.