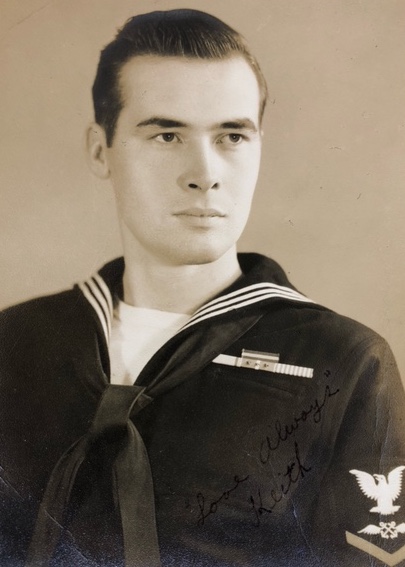

AB2 Keith Bunton, U.S. Navy – Serving on USS Essex During the Korean War

Less than five years after the end of World War II, the United States again found itself at war, this time on the Korean Peninsula fighting Communist aggression. Despite 1.8 million U.S. military members serving in the theater of operations during the bloody three-year conflict, Americans know little of their service and sacrifice. Aviation Boatswain’s Mate Second Class Keith Bunton, U.S. Navy, experienced the Korean War off the shores of Korea onboard the aircraft carrier USS Essex (CVA 9), which launched airstrikes against enemy targets during two Korean War deployments. This is Petty Officer Bunton’s story.

Keith Bunton was born in rural Missouri in 1931 and lived there until he was eight years old. His family then moved to a place in the country outside Memphis, Tennessee, so his father could raise greyhounds for racing. The family spent their summers in Memphis and then loaded the dogs into kennels mounted on the back of their 1937 Chevy pickup truck for the three-day trip to Jacksonville, Florida, where they stayed with the dogs as they raced over the winter. After the winter racing season ended, they packed up their belongings and returned to Memphis to start the cycle over again. Eventually, Keith’s father was able to build a house in Jacksonville and the family moved there permanently near the end of November 1941. Two weeks later, Keith was playing on the floor in the living room when he heard on the radio Pearl Harbor had been attacked and the United States was at war.

Keith’s father worked at Naval Air Station Jacksonville throughout World War II. When Keith was sixteen, his father started a chicken farm across the St. John’s River from downtown Jacksonville. Keith worked on the farm, too, and the hard physical labor kept him in great shape. Then, on June 27, 1950, the Korean War broke out when North Korea crossed the 38th parallel and invaded South Korea. The United States came to South Korea’s defense, as did other countries serving under the flag of the United Nations.

With the Korean War raging and his father having quit the chicken business, Keith enlisted in the Navy in January 1951. After being inducted in Jacksonville, he boarded a train on a Monday evening and arrived in San Diego for boot camp on mid-Friday afternoon. Since he was already in great shape, he did not find boot camp difficult, although it did bulk him up. When he arrived in San Diego, he was 6’4” and weighed 155 pounds. When he graduated from boot camp less than two months later, he weighed 180 pounds—the most he’s ever weighed in his life.

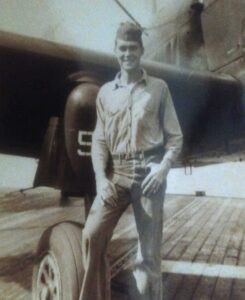

Now a Seaman Apprentice (E-2), Keith received orders to report to the USS Essex (CVA 9), a famous aircraft carrier that had participated in numerous campaigns in the Pacific during World War II. The Essex had recently arrived in San Diego after completing a two-year overhaul in Bremerton, Washington. Keith arrived onboard at the end of March 1951 and by August he was underway with the ship headed for the Korean War.

Keith spent his first fifteen months working on the carrier’s flight deck. The job was dangerous even during peacetime because the whirring propellors and jet engine intakes of the ship’s embarked aircraft were unforgiving if a sailor came too close. Keith’s primary job on the flight deck was to refuel the aircraft prior to their launch. To refuel the F-9F Panther jet fighter, the plane had to be positioned so its main landing gear was only about two feet from the edge of the flight deck toward the bow on the starboard (right) side. Then Keith would connect a two-and-a-half-inch fuel hose originating under the flight deck to jet’s fuel tanks after climbing up a ladder onto the wing.

When a new sailor tried refueling an F-9F Panther for the first time, all the experienced sailors in the area gathered around to watch. As the jet’s fuel tanks reached about half-full, the landing gear strut near the edge of the ship would suddenly jerk down two or three inches from the weight of the fuel. The rookie sailor on the jet’s wing would frantically try to grab onto anything he could, fearing he was about to plummet off the ship together with the jet. The scene never failed to delight the gathered onlookers.

Other incidents had far more serious consequences. Occasionally, a plane returning from a combat mission would have problems landing and slide off the flight deck into the sea. On September 16, 1951, a combat damaged F2H Banshee jet fighter jumped the barriers when trying to land and crashed into other aircraft staged on the carrier’s flight deck. Seven men died and the Essex had to pull into Yokosuka, Japan, for repairs. On another occasion a sailor was severely injured when a parked plane’s jammed gun suddenly opened fire. Sometimes, though, the ship got lucky and no one would be injured. Keith remembers a plane landing with a bomb still under its wings when the bomb detached and skidded down the flight deck. Before it could explode, a sailor ran over to it, picked it up, and threw it over the side of the ship into the water.

Although Keith’s living quarters were cramped, he describes them as much better than what men in the other services had to endure in Korea. He lived below decks in a compartment with seventy other men, their racks (bunks) stacked three high. Each sailor was assigned two gray wool blankets and a locker to stow his personal belongings. Keith folded one of his blankets and used it to extend the length of his mattress because the Navy-issued mattress was too short for his 6’4’’ frame. When Keith wasn’t on duty or asleep in his rack, he spent a lot of time reading books as there was little else to do for entertainment.

The Essex returned to San Diego from her first Korean War deployment in March 1952. Just four months later, and after Keith was able to take some well-deserved leave back in Jacksonville, the Essex deployed again for a second Korean War deployment, departing San Diego in July 1952. For Keith, this cruise began much like the last one ended, with him continuing to work as an Aviation Boatswain’s Mate on the carrier’s flight deck. However, after he’d been on board a total of fifteen months, he was assigned below decks to the gasoline filter room, where he was responsible for opening and closing valves that controlled the flow of aviation fuel. When General Quarters sounded, he had three minutes to get from wherever he was to his duty station in the gasoline filter room, which required him to pass through four watertight steel hatches. He found this a little unnerving because as hard as it was to get through those doors to his station, he knew it would be even harder, if not impossible, to get out if something went wrong.

During both of Keith’s wartime deployments, the Essex made several port calls along the way. These stops included Pearl Harbor at the beginning and end of each deployment, Yokosuka, Japan, and Subic Bay in the Philippines. Keith remembers Subic Bay being intolerably hot and uncomfortable because the ship had no air conditioning. In Yokosuka, he remembers visiting Yokohama just north of Yokosuka and seeing cars burning charcoal for fuel instead of gasoline, an alteration made necessary by oil shortages during World War II.

After the Essex returned to San Diego from its second Korean War deployment in January 1953, Keith transferred to Moffett Field, located in Santa Clara County, California, at the south end of San Francisco Bay close to what is now Silicon Valley. Keith was assigned to Transport Squadron VR-5, which operated four-engine Douglass R6Ds (DC-6s) out of one of the giant blimp hangars built by the Navy during the 1930s and 1940s to support its dirigible program. The blimp hangars were so gigantic they could accommodate five of the big R6Ds from Keith’s squadron and five more from another squadron.

Keith’s job at Moffett Field involved directing aircraft taxiing back to the hangar area to their assigned parking spots. When not on duty, Keith and his friends would head to the Enlisted Men’s Club when it opened at 4:00 p.m. for a few beers and then hurry to the chow hall for dinner by 5:45 p.m., just fifteen minutes before the facility closed. Keith also spent a lot of time touring Palo Alto and San Jose, but never made it to San Francisco, despite being so close.

Keith served out his enlistment at Moffett Field and was honorably discharged in December 1953 as an Aviation Boatswain’s Mate Second Class (E-5). He returned to Jacksonville, Florida, got married, and began a long civilian career working as an aviation metalsmith at Naval Air Station Jacksonville. He worked at Naval Air Station Jacksonville for thirty-two years, finally retiring in 1986. He has two wonderful children, his son, Chris, and his daughter, Melinda. As he looks back over his ninety-one years, he sums it by saying “I’ve had a good time in life”.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Aviation Boatswain’s Mate Second Class Keith Bunton, U.S. Navy, for his distinguished service aboard USS Essex during the Korean War and for his thirty-two years of service as an aviation metalsmith at Naval Air Station Jacksonville. His nearly four decades of service helped bring democracy to South Korea and preserved Navy combat readiness. We thank Keith for all he has done for our country and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Keith’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.