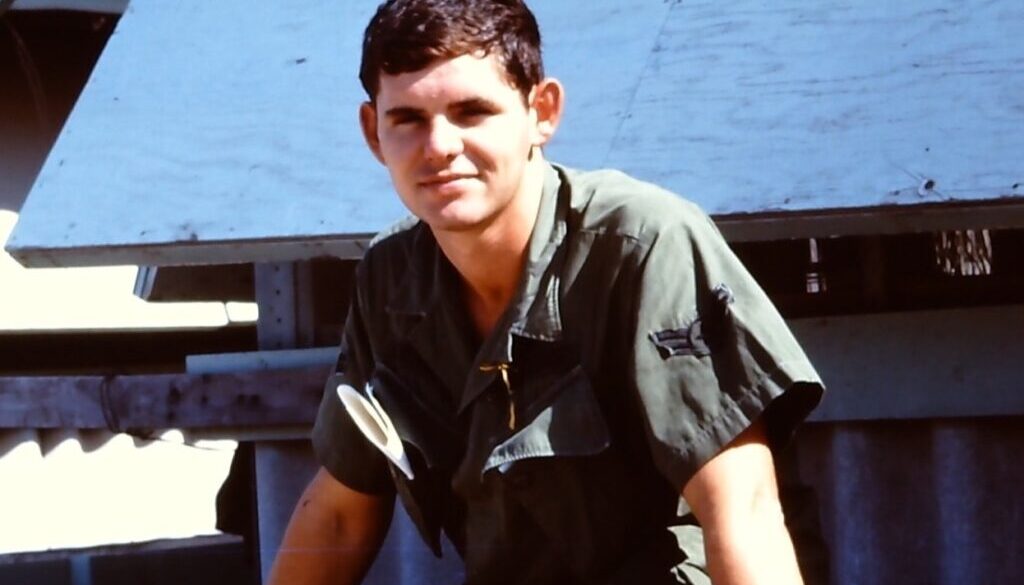

Staff Sergeant Dean Moss, U.S. Air Force – “A Year in Nha Trang: 1968-69”

Destiny has a way of just happening, whether you want it to or not. Staff Sergeant Dean Moss, U.S. Air Force, knows that all too well. No matter how many times he tried to point his life in a particular direction, destiny kept bringing him back to where he was meant to be. He was destined to serve our country in Vietnam, where his expertise with armaments would help protect American lives. And, he was destined to marry Barbara, his wife of fifty-two years, despite his impending deployment to a war zone and not knowing if he would ever return. This is his story.

Dean was born in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1947. He attended Atlanta city public schools, graduating from Franklin D. Roosevelt High School in 1965. Although he did not know her well yet, his future wife, Barbara, graduated from the same high school one year ahead of him. Since senior girls did not normally associate with junior boys, their romance was yet to be.

Dean’s graduation from high school in 1965 was bittersweet. He was thrilled to be moving on to the next stage of his life, but he also knew graduation meant the very real possibility of being drafted to fight in the rapidly escalating war in Vietnam. Against that backdrop, he enrolled in his local community college to study electronics, giving him a deferral from the draft. His courses were technical and vocationally oriented, rather than degree oriented, and he really enjoyed the hands-on work. As an offshoot of his studies, he earned his FCC license and became a HAM radio operator. The two-year course of study also gave him the opportunity to begin dating Barbara now that the junior/senior distinction of high school was gone.

Dean finished his electronics studies in 1967 and immediately received a notice to report for his pre-induction physical. Concerned with the prospect of being drafted into the Army or the Marines, he visited his local Air Force recruiter. The recruiter told him his two years of electronics training would allow him to bypass the Air Force’s introductory electronics school at Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Mississippi, and immediately get to work in the electronics field. That sounded good to Dean, so he committed to the Air Force, enlisting in the delayed entry program in June 1967, with a report date three months later.

Dean’s parents and Barbara weren’t thrilled with Dean’s enlistment. He was an only child, so his parents were understandably worried. Barbara also worried because she had no idea what lay in store for Dean now that the Air Force owned him for the next four years. Dean reassured them his Air Force enlistment protected him from the draft and he would be safe. So, with heavy hearts, they bid Dean farewell in September when it came time for him to honor his commitment.

Dean reported for Basic Training at Lackland Air Force Base in September 1967. After graduating, Dean was shocked to learn he was being sent to Armament School at Lowery Air Force Base in Denver, Colorado. There, instead of commencing work in electronics as the recruiter had promised, he would learn how to arm airplanes with bombs, rockets, guns, and missiles. He also surmised that meant he would be headed to Vietnam as soon as he finished his training, rather than working on electronics systems stateside or in Europe.

Mustering all of the intestinal fortitude he could as a newly-minted Airman (E-2), Dean approached his sergeant and told him his new orders had to be a mistake. He told his sergeant he believed he was supposed to be working on electronics and the orders should have been to Keesler Air Force Base in Mississippi, not Lowery Air Force Base in Colorado. Dean’s sergeant left no room for misunderstanding. He told Dean he was in the Air Force now and would be assigned based on the needs of the Air Force, not his desires or what he thought he had been promised. He told Dean he was going to be a weapons mechanic and he better get used to it.

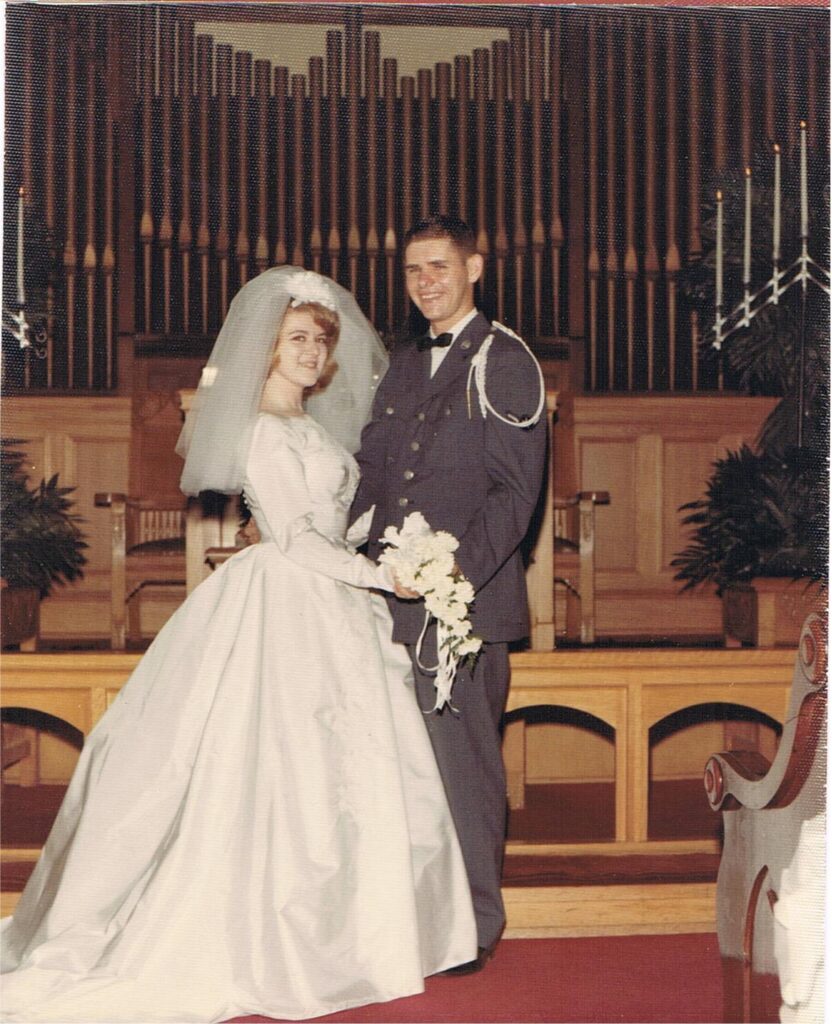

Dean reported to Lowery Air Force Base as ordered and learned all about the art of arming aircraft. In week eleven of the fifteen-week course, Dean received orders to his first duty station: the 4th Air Commando Squadron in Pleiku, Republic of South Vietnam. While it was bad enough receiving orders to Vietnam, what he dreaded even more was calling Barbara and his parents to tell them the news. With coverage of the bloody Tet Offensive having recently played out on televisions all across America, their reaction was predictable. Dean also talked with Barbara about their future, not wanting her to commit to someone who was about to be sent to a war zone. That didn’t matter to Barbara, so after much thought and prayer, Dean proposed to her during a call he made from a phone booth in Colorado. After she accepted, Dean committed himself to finishing his training at Lowery, where he graduated as an Honor Graduate in April 1968.

After graduating from Armament School, Dean took thirty days leave. He went home to Atlanta on April 17th and married Barbara on May 4th. Behind the scenes and unbeknownst to Dean, his mother wrote their Congressman to request that Dean not be sent to Vietnam given he was the only male child in their family’s line. She told the Congressman if he died, there would be no one to carry on the family name. Her request was denied.

On May 20, 1968, just sixteen days after marrying Barbara, Dean found himself kissing her goodbye at Atlanta’s Hartsfield International Airport. It was the hardest thing Dean would ever do, not knowing if he would ever see her again. He then flew from Atlanta to Seattle, Washington, where he reported to McChord Air Force Base for further transit to Vietnam. At McChord, he and servicemen from all the other services boarded a chartered Northwest Orient flight bound for Vietnam. They flew nonstop to Tokyo, where the plane refueled and English-speaking Japanese stewardesses replaced their American counterparts for the final leg of their journey.

The flight landed in South Vietnam after dark at Cam Ranh Bay Air Base, located approximately 180 miles northeast of Saigon. Dean hadn’t been given any real training on what to expect other than to make sure he had a will and had given his wife a power of attorney, so everything about Vietnam surprised him. He hadn’t expected a lush tropical climate, nor had he been informed about the magnesium star shells that would be lazily descending over the base at night to help ward off would-be attackers. So, when Dean got off the plane and saw a flair floating over the base on a parachute, he wondered if the base was under attack. Even more worrisome, he’d received no training on things he’d heard about like booby traps and grenade attacks. All he’d had was M16 rifle training, but he’d not been issued a rifle or battle gear, so he felt very vulnerable. It made for a stressful transit from the flight line to the barracks and for a sleepless night once there, where he not only had to cope with the intense tropical heat, but also had to fight off a multitude of Vietnamese mosquitoes trying to welcome him to his new home.

The next morning, Dean boarded a C-130 cargo plane headed for Pleiku in South Vietnam’s Central Highlands. The plane made a spiraled approach into the airfield at Pleiku, causing Dean to hang on for dear life as it felt like the airplane was crashing. Once on the ground, he found it noticeably cooler than Cam Ranh Bay, especially since the monsoon season was just beginning. As per his orders, he reported to the 4th Air Commando Squadron, which operated AC-47 gunships, known as “Puff the Magic Dragon”. Each plane was equipped with three Gatling guns (called miniguns) that in a matter of seconds could saturate an area the size of a football field with thousands of 7.62-millimeter machine gun rounds. The squadron wanted Dean to man one of the airplane’s miniguns during flights to make sure it fired when needed. Unfortunately for the squadron, Dean did not have the level of training required for the job and they did not have time to train him. They told Dean they were going to send him back and, at least for a moment, Dean thought that meant he would be going back to the States.

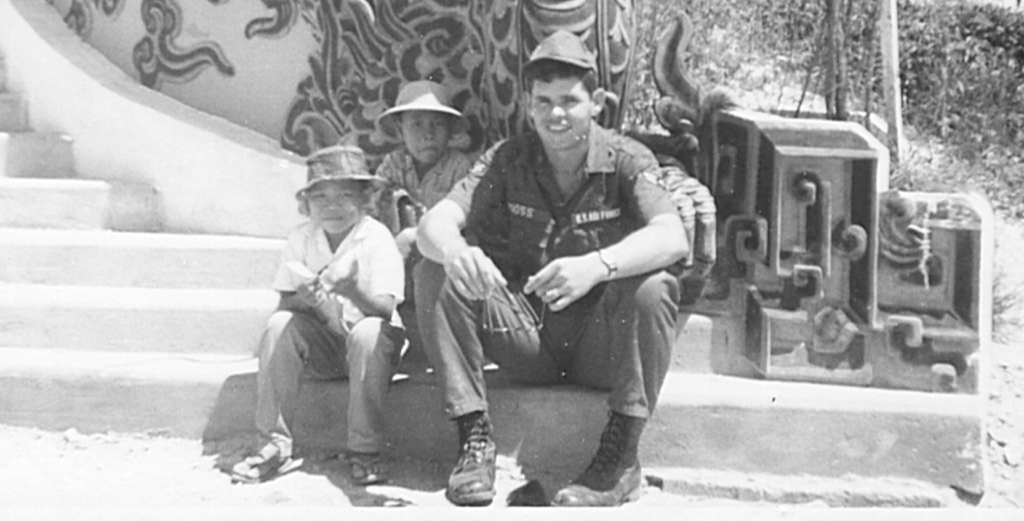

Instead, Dean was sent to the 21st Tactical Air Support Squadron (TASS) in Nha Trang, located on the coast just twenty-seven miles north of Cam Ranh Bay. The 21st TASS operated the single-engine Cessna O-1E “Bird Dog” and its replacement, the twin-engine Cessna O-2A. These slow-moving and vulnerable planes provided Forward Air Control (FAC) guidance to tactical aircraft and helped artillery units and even ships at sea attack enemy forces on the ground. In addition to radioing target coordinates, the Bird Dogs fired white-phosphorous rockets at enemy positions to mark their locations with smoke. Attack planes would then swoop in to deliver bombs and other ordnance on the targets. After the attack, the slow-moving Bird Dogs would again fly low over the enemy positions to assess the damage and, if necessary, call in another attack. It was dangerous work; often the planes came back riddled with bullet holes. With the pilot’s and spotter’s lives at risk on every mission, it was crucial the planes’ rocket launchers worked as intended. Dean’s new job was to make sure they did.

Keeping the rocket launchers in working order meant keeping them clean and making sure the rockets went where they were aimed. On one occasion, a pilot returned from a mission and reported the rockets were hitting left of target. When Dean inspected the plane, he found the metal sight extending vertically from the engine cowling had been bent to the left. He straightened it out and reported the problem solved. Before the plane could be considered fully mission capable, though, it had to undergo a functional check flight (FCF). The FCF pilot asked Dean to go along in the spotter seat behind the pilot. The two men flew until they found a deserted hut on stilts near a riverbank. Having been cleared to test the rockets, the pilot made a textbook approach toward the hut and fired two rockets, scoring direct hits and setting the burning hut adrift down the river. Unfortunately, the hut had not been completely deserted, but was occupied by a bunch of chickens who did not fare well in the blast. The pilot told Dean not to tell anyone what had happened, but somehow word leaked out. As a result, the pilot’s call sign was changed to Colonel Sanders and someone stenciled a dead chicken on the side of his airplane.

Despite arming planes daily with rockets, at times it was hard for Dean to remember he was in a war zone. His barracks was just across the road from where he worked, so going to work was easy. The mess hall always had hot food—it might have been powdered milk and powdered eggs—but Dean was keenly aware it was better than what the soldiers fighting in the jungle were getting. The base even had a beach designated as a U.S. Armed Forces Beach where people could swim or sunbath. The reminder of exactly where he was came in the form of North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong mortar attacks, which happened frequently. The attacks were primarily aimed at the airfield and the planes, but occasionally 81-millimeter mortars would stray into the barracks areas. Dean knew if a mortar hit his barracks, it would turn out badly, but there was nothing he could do about it, so he didn’t dwell on it.

One very popular amenity on the base was a nine-hole putt-putt golf course built on the beach by the base’s Red Horse Squadron (a heavy construction unit). During most mortar attacks, it seemed like the NVA and Viet Cong saved their very last round for the putt-putt course, believing its destruction would adversely impact American morale. Dean said the attacks didn’t achieve their goal, though, because the putt-putt course was often the first thing repaired and back in action after an attack.

For Christmas 1968, Barbara sent Dean an eighteen-inch, fully decorated Christmas tree. Dean’s barracks chief permitted him to plug in the lights as long as he was in his quarters, so it brought a touch of Christmas cheer to Dean’s home away from home. The chapel also helped bring in the holiday by building a nativity scene on a grassy spot just outside the chapel. To represent Mary, Joseph, the baby Jesus, and the three wise men, the chapel wrote the Spiegel catalog company and it sent the chapel mannequins. The parachute shop made costumes for the mannequins and the nativity scene turned out beautifully. One night after it had been set up, two or three mortars hit right outside the chapel and blew the nativity scene apart, destroying all the characters except the baby Jesus. Dean said the following Sunday, there were a lot of extra people attending services at the chapel!

One other memorable Christmas event involved Dean’s selection to attend the Bob Hope USO Christmas Show being held on December 23rd at Cam Ranh Bay. He and the other airmen lucky enough to go were loaded into a truck for the twenty-seven mile drive south along the coastal highway. Everyone was particularly excited about the prospect of seeing Ann-Margret, so all were equipped with their cameras and lots of film. None, however, carried a weapon, so they joked the truck could have been commandeered by a Viet Cong guerilla with a pocketknife. Fortunately, that didn’t happen, and Dean and his friends enjoyed the show and made it back safely.

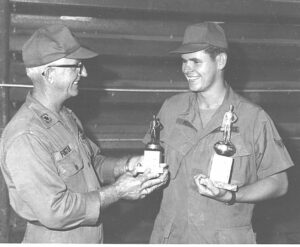

Because of his background in electronics, Dean was especially suited for working with the rocket launcher’s control system and wiring. On his own initiative, he developed a way to test the adequacy of the voltage being sent through the launching system, which earned him a certificate and a twenty-dollar bonus from the Air Force’s beneficial suggestion program. His knowledge was really put to the test when his squadron was tasked with completely rebuilding a Bird Dog badly damaged in a crash. The plane was in such bad shape that it had to be airlifted back to Nha Trang by a heavy-lift helicopter.

Dean’s NCOIC (non-commissioned officer in charge) asked him if he thought he could rewire the rocket launcher system by himself. Dean responded “absolutely” and spent the next two days doing so. When he finished, though, the system wasn’t registering the required voltage. Dean checked everything but couldn’t find the problem. Finally, he reported his failure to his NCOIC. Rather than chew him out, Dean’s NCOIC told him to take a break and come back in a couple of days with a clear head. Dean did, and to his surprise, the system worked flawlessly without him doing a thing. He initially suspected his NCOIC had found the problem and fixed it on his own, but his NCOIC assured him he had not. They then discovered what the problem was—the voltage meter Dean had used to test the system the first time had a faulty fuse. Now that he was testing with an accurate voltage meter, his rewiring of the system proved perfect.

Despite being just an Airman First Class (E-3), Dean was recognized as an expert in his field. He was selected as the 7th Air Force Munitions Maintenance Mechanic of the Quarter and received a similar semi-annual award. He also taught and certified Airmen assigned to Forward Operating Locations on safely handling explosive ordnance and loading aircraft rockets. For his final Airman Performance Report, Dean was ranked in the top 1% of Airmen, making him feel very proud.

Consistent with tradition, Dean marked the beginning of his final month in South Vietnam by wearing the ribbon from a bottle of Seagram’s VO whiskey on the top button of his uniform shirt. One week prior to departure, he tied the ribbon into a bow. Finally, in May 1969, one year after arriving at Cam Ranh Bay, Dean boarded an outbound flight and departed South Vietnam for home.

Dean’s flight landed at McChord Air Force Base and he and five other service members hired a taxi to the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. On the way there, the taxi rear-ended another vehicle and Dean hit his knee on the front console, causing him to limp slightly when he finally got out of the cab. At the airport, the only welcome Dean received was from war protestors, who heckled him as he limped along. One individual stayed close behind him, but Dean ignored him until the man called him a “baby killer”. Dean turned around and said, “I’m not a baby killer, so back off and leave me alone.” The protester responded by spitting in Dean’s face. Dean still has the scar on his hand from where he broke the heckler’s nose.

Dean returned to Atlanta and into Barbara’s welcoming arms. Because he had enlisted instead of being drafted, he still had two-and-a-half years to serve on his enlistment. The Air Force assigned him to the 428th Tactical Fighter Squadron at Nellis Air Force Base, so he and Barbara packed up and moved to Las Vegas, Nevada, to complete Dean’s service commitment. Dean was honorably discharged in September 1971 after turning down a $10,000 variable reenlistment bonus. He was ready for his civilian life to begin.

After being discharged, Dean and Barbara returned to Atlanta, where Dean took a job with a medical supply company. The job was short-lived because in June of 1972, Dean received a call from the federal government offering him a position with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) working on instrument landing systems. Dean took the job and in 1977, relocated to Knoxville, Tennessee, where he stayed with the FAA until he retired in 2009.

On Dean and Barbara’s 40th wedding anniversary, they began an amazing year-long journey together. Remembering they had written each other every day when Dean was in Vietnam, they went into their attic and retrieved the letters they had sent each other, having saved them in a box for all these years. Instead of reading them all at once, they read the letters to each other on the same day they were written forty years before. The year-long experience rekindled so many memories for Dean that he began to take notes, creating a detailed journal of his experience in Vietnam. Dean used the journal to write a fascinating memoir of his year in Vietnam. You can read Dean’s memoir, The Other Side of the World, for an even deeper understanding of his service in Vietnam.

Dean and Barbara have two sons. David, the youngest, is serving as a Lieutenant Colonel in the Air Force. When David deployed to Iraq and had to spend a Christmas there, Dean and Barbara retrieved from the attic the Christmas tree Barbara had sent to Dean in Vietnam almost fifty years before. That little Christmas tree has thus brightened the spirits of two generations of service members in two war zones. Dean and Barbara’s other son, Scott, is serving as a Captain in the Navy. Sadly, Dean’s beloved wife, Barbara, passed away in 2020. They had been married for fifty-two years.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Staff Sergeant Dean Moss, U.S. Air Force, for his distinguished service in Vietnam during the Vietnam War. Although far from home and the people he loved, he dedicated his heart and soul to his duties, making sure the systems he was responsible for functioned properly, saving American lives. We are proud of what Dean has accomplished in his life and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Dean’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.