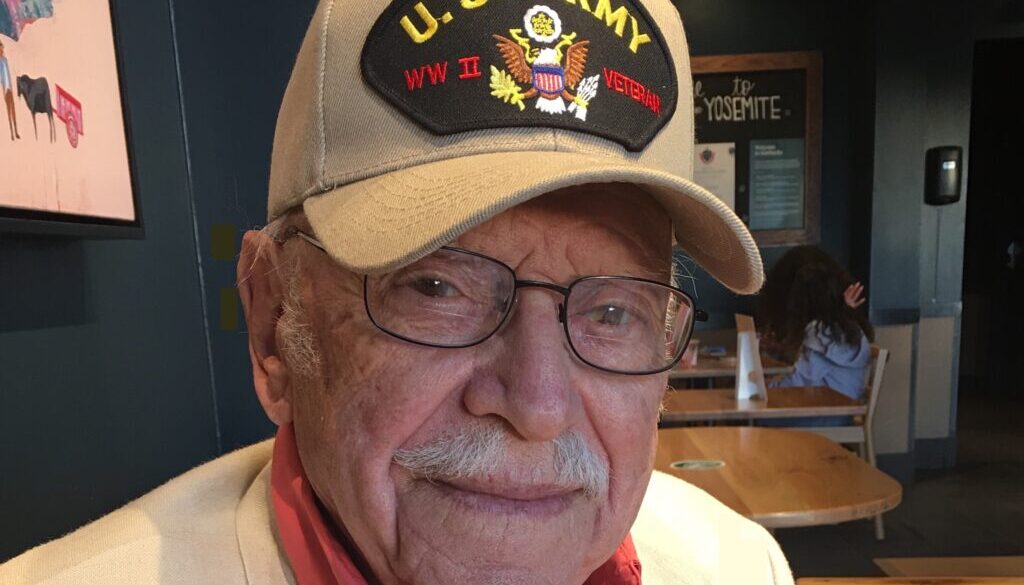

Staff Sergeant Howard A. Berger, U.S. Army – Five Decades of Service

Sometimes when you’ve got your heart set on something, that’s all you can see. Your focus can cause you to miss even better opportunities that might present themselves in unexpected ways. Staff Sergeant Howard Berger had that kind of focus in February of 1946, looking forward to going home from Austria after having served in the U.S. Army in Europe at the end of World War II. He, however, took a chance on a pop-up interview in Vienna and it led to a wonderful career and a lifetime of service to the Army. This is his story.

Howard was born in November 1923 in The Bronx and raised in Brooklyn, New York. His family lived in an apartment in a house purchased by his grandparents after they immigrated from Eastern Europe. Howard’s father, who had served as a machine gunner in World War I, was a successful salesman at a New York clothing store, Maxi’s, while his mother raised Howard and his younger brother at home.

Both Howard and his brother walked to and from their neighborhood schools. One afternoon in May 1937 when Howard was walking home from middle school, he stopped at a playground along the way and climbed onto a swing. As he swung back and forth, he looked up into the sky and saw a giant white blimp flying very slowly overhead. He thought the blimp looked beautiful until he saw the Nazi swastika on its fins. Later in the day, he heard on the news the blimp was the German airship Hindenburg, and that it had exploded with great loss of life as it attempted to dock at Naval Air Station Lakehurst in New Jersey.

After Howard graduated from Eastern District High School in June 1940, he went to work as a messenger in the heart of Times Square on 42nd Street in New York City. Scanning through the want ads one morning, he saw a job that interested him working for the Curtis Publishing Company. He asked his boss if he could apply and his boss not only told him yes, but also said if the job was better than what he had now, he should take it. His boss also promised Howard if the new job didn’t work out, he would always have a messenger job waiting for him when he returned.

The job with Curtis Publishing involved selling subscriptions door-to-door for the company’s most popular magazines, The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies’ Home Journal, and Country Gentleman. Since Howard’s father was a salesman and Howard had sales in his blood, he decided to give it a try. When he first went out, his new boss showed him what he needed to do. Although he was a little nervous, Howard earned $6.00 in the first week. By the fourth week, he was making $24.00. Once he fully learned the ropes, he was earning up to $100.00 each week, making him the primary breadwinner in his family. In addition to the good pay, the job taught Howard how to quickly size up and get along with lots of different kinds of people – “the good, the bad, and the ugly”.

In October 1942, Howard’s sales territory included an area in New Jersey with a number of defense factories, which were going full bore in support of the war effort. Seeing these factories in action convinced Howard he needed to enlist to do his part. His brother wanted to enlist too, so together they went to a local recruiting office in New York to sign up. Howard was eighteen and old enough to enlist, but since his brother was only seventeen, the recruiter would not let his brother enlist without their father’s signature. With that, the brothers left the recruiting office and walked around the corner, where Howard signed his father’s name. The brothers then returned to the office and both were permitted to enlist – Howard in the Army and his brother in the Coast Guard. Howard is sure the recruiter knew what they had done, but he also figured the recruiter didn’t care. As long as the recruiter could point to a signature Howard and his brother said was their father’s, that was all the recruiter needed.

Although the recruiter wasn’t upset with what Howard had done, Howard’s father was. When the brothers got home and told their parents they had enlisted, Howard’s father was furious—not so much because the boys had enlisted, but because Howard had signed his name. He did not, however, attempt to invalidate the agreement and he let both boys serve. Howard’s brother went on to serve successfully in the Coast Guard, sailing on ships protecting Lend-Lease convoys in the North Atlantic and becoming a police officer in New York City after the war.

Howard’s military service began when he reported for active duty on November 13, 1942, one day after his nineteenth birthday. He was initially mobilized at Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, but shortly thereafter was sent to Fort Dix, New Jersey, for in-processing. After a few weeks at Fort Dix, Howard was sent to basic training at Camp Stewart, Georgia, just outside of Savannah.

What stands out most for Howard about basic training was getting shots and working in the mess hall on “Kitchen Police” duty, better known as “KP”. He remembers being roused out of bed at 4:30 a.m., getting up to three shots at a time by 5:30 a.m., and then being sent back to work in the kitchen scrubbing pots and pans and preparing meals. The trainees thought the mess sergeant particularly mean because he would give no one a break, no matter how sore their arms might be after the shots.

After basic training, Howard continued training at Camp Stewart at the Army Antiaircraft Artillery Center. Initially assigned to the 490th Antiaircraft Artillery – Automatic Weapons (AAA) Battalion, and then the 454th AAA Battalion, Howard trained in halftracks with four 50-caliber machine guns in a quad mount in the bay at the rear of the vehicle. The unit also had a 40-millimeter Bofors antiaircraft gun, which had to be towed behind a truck. When it came time for the unit to deploy to Europe, a cadre of soldiers that included Howard stayed behind to train the next unit. Howard was then assigned to Battery “D” of the 580th AAA Battalion. He trained with the unit on maneuvers in Louisiana in 1944 and then returned to Camp Stewart to prepare to deploy to the European Theater for action against the Nazis.

In December 1944, Howard’s unit traveled to New York for the trip to Scotland. Howard, now a staff sergeant leading a platoon comprised of twenty-one soldiers and four halftracks, boarded the Queen Elizabeth (a luxury ocean liner converted to a troop ship for the war) along with the other members of his platoon and 15,000 other soldiers. The ship soon set sail into the heavy seas of the wintry North Atlantic. The seas were so rough, the ship turned south to Bermuda before heading west toward Europe, all the time zigzagging to avoid attacks by German U-boats. Although Howard didn’t get seasick, many others did, making it a wretched voyage for all onboard. When the ship finally arrived in Greenock, Scotland, just a few days before Christmas, sunny weather and a beautiful day brought an end to their European cruise.

After getting off the ship in Greenock, Howard and his men boarded a train and were taken to a small farm town, where they unloaded their gear and set up their sleeping arrangements in an area known as Camp Codford. While they were working, a giant explosion came out of nowhere and shook the ground. A German V-2 rocket with a 2,200 pound warhead had hit in their vicinity, and although no one in the unit was hurt, it “scared the hell” out of all of them. They didn’t stay at Camp Codford long, as their next assignment was to assist with the coastal defenses in the resort town of Bornemouth, located on the south coast of England. From there, they reported to a park in Southampton, where they stood guard at a British camp for Italian prisoners of war (POWs). The duty was easy because the Italian soldiers were happy to be POWs and did not want to escape. In the camp, they were treated well and had good food. Howard’s POW camp duty ended in March of 1945, when Howard’s unit loaded on a ship together with their halftracks and crossed the English Channel, landing in France.

Once in France, Howard and his platoon climbed into their halftracks and drove across northern France and Belgium and on into Germany. As the Allied armies had already cleared this area, they were not involved in any fighting, but as an antiaircraft unit, they were always on alert for enemy aircraft and the possibility of German paratroopers trying to get behind Allied lines. When Howard’s unit crossed into Germany near the city of Aachen, Howard saw for the first time the casualties of war. Dead German soldiers lay strewn around on the ground, frozen by the bitter winter cold in macabre poses reflecting their last moments of life. Although Howard can still see the images of the lifeless men today, he didn’t have time to dwell on it then as his unit continued driving further into Germany towards the retreating enemy.

Howard reached the Rhine River near the town of Remagen, where weeks before, the U.S. Army’s 9th Armored Division captured the Ludendorff Bridge intact, allowing tens of thousands of Allied troops and their equipment to cross in hot pursuit of the German army. The bridge at Remagen helped bring the war to a speedy conclusion. By the time Howard arrived, the bridge had collapsed, but Army engineers had constructed pontoon bridges over the river, allowing Howard’s halftracks to cross.

After a day of progress on the other side of the Rhine, Howard pitched his tent for the evening. The camps were always in blackout conditions at night to protect from enemy attack, but a lone jeep usually managed to navigate to the camp to bring the unit its mail. That was when Howard learned his best friend from school, Harold Marin, had been killed in Belgium. Harold was a promising young boxer, but now he was gone. Howard was so angry he took his rifle and set out looking for German soldiers to exact revenge. Looking back, he is glad he didn’t find any, and even more glad no German soldiers found him.

On May 5, two days before Germany surrendered, Howard’s unit repositioned to a farm and Howard’s platoon occupied an empty farmhouse. The farmhouse offered a unique opportunity – a hot bath instead of having to wash with water poured into a helmet. To get the “bath” ready, water had to be heated on a stove in the kitchen and then poured into a large tub for reasonable bathing. As Howard readied for his bath, he got undressed and took a c-ration can filled with gasoline and tossed the gasoline into the stove to get the fire going. When the gasoline hit inside the hot stove, it blew up and spewed flaming liquid on Howard’s hands and his left leg. Howard ran outside to a nearby air raid shelter and put out the flames by covering them with sand. Still, he was badly burned and had to be immediately medevac’d. A medic had him placed on a gurney and loaded onto a ¾-ton truck for the drive to the closest tent hospital, with some of the men from his platoon going along to cheer him up and make sure he was taken care of.

At the tent hospital, he was triaged along with other injured soldiers. When it was Howard’s turn, a doctor and two nurses attended to him. They told him they were going to put him to sleep to treat him, but Howard refused because he was afraid they were going to amputate his leg, which by now was completely black. The doctor said okay and then instructed the nurses to clean all of the sand from Howard’s burns, which was very painful. They then bandaged his wounds and moved his gurney to a recovery area, where he lay on a stretcher on the ground with other recovering soldiers. He tried to get some sleep, but every three hours he had to get a shot and take medication, making for quite a long night.

The next day, Howard and other injured soldiers were flown to Paris in a B-25 medium bomber converted into an air ambulance. Howard’s gurney had a tag on it that said “UK”, meaning he was to continue on to England to recover. However, as he waited in the Orly Airport terminal for the next flight, an announcement came over the PA system saying all burn patients would now be treated in Paris. As a result, Howard was transported by ambulance to L’Hopital Beaujon in Clichy, Paris. Once there, the doctors told Howard he would be as good as new in thirty days, as long as he did exactly as they said. That was all Howard needed to hear and he followed their instructions to the letter.

As the doctor promised, Howard was released from treatment in thirty days, but he remained at the hospital for observation to make sure there were no follow-on issues or infections. He was, however, allowed to tour Paris during the day, an opportunity he took full advantage of. With the war over and everyone celebrating, it was a good time to enjoy the city. At the end of the thirty-day observation period, he was sent to Nuremburg, Germany, and told to wait for the 580th AAA Battalion to send someone to pick him up. While he waited, he was able to attend a USO show on the 4th of July at Soldiers Field starring Jack Benny, Ingrid Bergman, Larry Adler, and many other stars of the day. After the show, he boldly went backstage and introduced himself to the stars. He has a ten mark note signed by Jack Benny, Ingrid Bergman, and Larry Adler to show for it.

Although the Allies celebrated VE Day (Victory in Europe Day) on May 8, 1945, the war with Japan still raged on. In recognition of that reality, the 580th AAA Battalion received orders to relocate to Austria to begin training in anticipation of being transferred to the Pacific theater for action against Japan. Howard rejoined the battalion as it made its way to Austria. On the way, the unit stopped for approximately one week in the town of Berchtesgaden in the Bavarian Alps. This was the site of Adolf Hitler’s Alpine retreat, known as the Eagle’s Nest.

The unit eventually stopped moving once it arrived at Wallersee Lake, a picturesque resort area near the Austrian city of Salzburg. Given the war with Germany had just ended, no tourists were using the resort, so Howard’s unit took over an empty resort hotel and made it their headquarters. They also were able to relax a little, getting time off from duty on weekends beginning at 8:00 a.m. on Saturday morning. However, due to an order the men attributed to General George Patton, they had to continue wearing their steel helmets on Saturdays until 12:00 in the afternoon. Then they could take them off for the rest of the weekend. Rigid requirements like this made General Patton unpopular with Howard and his men, although they respected him as a great tactical commander.

The preparations for sending the 580th AAA Battalion to the Pacific ended after President Harry Truman authorized the use of two atomic bombs against Japan and the Japanese Government formally surrendered on September 2, 1945. The unit wintered in Salzburg, Austria, with soldiers singularly focused on returning home to the United States as soon as they accumulated enough points to allow their departure. Soldiers earned one point for each month they had in the Army, one point for each month they spent overseas, five points for each campaign they were involved in, five points for a medal of merit or valor, five points for a Purple Heart, and twelve points for each of up to three dependent children.

Howard’s turn to go home finally arrived in February 1946. After shipping most of his belongings back to New York City and attending a farewell party the night before he was to leave, he prepared to depart on a morning train to Bremerhaven, where he would board a ship for the return voyage to the United States. As he was getting ready on the day he was to depart for the train station to begin his journey home, his captain called him to his office at 8:00 a.m. Howard assumed the captain was going to say goodbye again and wish him good luck. Instead, the captain informed him a TWX (an electronically sent typewritten message) had just come in saying the High Commissioner in Austria had finally reviewed an application Howard had submitted months ago to stay behind and work as part of the occupation forces in Austria. The TWX added Howard should report to Vienna for an interview as soon as possible.

The captain gave Howard a way out. He said Howard could get on the train to Bremerhaven and the captain would reply Howard was already on his way home. Howard thought for a moment. He was a twenty-two-year-old young man from Brooklyn—he would never have the opportunity to visit Europe again because it was too expensive to get there. He told the captain he’d go to the interview. Expecting not to be hired, he’d at least get to visit Vienna, the world-renowned capital of Austria, and would simply be delaying his return home by no more than a week or two.

A week later, Howard boarded a train known as the “Mozart” in Salzburg, headed for Vienna. At the time, Austria was divided into four zones, with each zone being administered by one of the occupying powers: the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. Vienna was surrounded by the Soviet zone, so when the train arrived at the border between the U.S. zone and the Soviet Zone, the train stopped and Soviet troops boarded to conduct a cursory inspection. The train then continued until it arrived in Vienna, which also had been divided into four zones, with the historical center of Vienna designated as a fifth central zone administered on a monthly rotating basis by one of the four occupying powers.

When Howard arrived at the train station in Vienna, he was met by military police, who escorted him to his quarters for the night. He was assigned to a two-person room on the first floor of an eight-story building. As both cots were empty when he arrived, he stowed his gear, cleaned-up, and then headed to the PX (post exchange) to buy some supplies before going to his interview the following morning.

At the PX, there were a lot of young Austrian women waiting nearby and hoping to meet an American GI. Knowing that, Howard bought some extra candy and cigarettes. As he came out of the PX, a pretty young Austrian woman asked him if he would like a tour of Vienna. He said he would, but first they needed to go back to his billets so he could drop off his purchases. When they returned to the building, the young woman waited outside because visitors were not permitted inside.

When Howard returned to his room and opened the door, a monkey jumped out towards him! Stunned, Howard carefully worked his way into the room to stow his purchases, but it took him extra time because he had to secure everything from the monkey. He then went to the front desk and complained, learning that a soldier who had served in Africa had arrived and brought his pet monkey with him. Howard said he wanted the monkey out, which happened later in the day. When Howard finally returned for his tour of Vienna, the pretty young woman was gone, apparently thinking Howard would not return. Howard cursed the monkey and its owner.

The next morning, someone from the High Commissioner’s Office (General Mark Clark was the U.S. High Commissioner for Austria) escorted Howard to the Civilian Personnel Office at the U.S. Army headquarters building on Alser Strasse. There he learned the position he was being interviewed for was Assistant to the Class VI Officer, which meant he would help account for alcohol sales to Army officer and enlisted clubs and U.S. embassies throughout eastern Europe. He spoke initially with a man named Vincent Mahler, who had him fill out some papers and then instructed him to go to another building a few blocks away for his interviews. He interviewed initially with a captain and then a major. When he told them he’d never worked in accounting before, they asked him if he knew what two plus two was. When he said four, they told him that was all he needed to know. Then they took him to meet the colonel, a huge man who had played center for the Army football team at West Point. The colonel asked Howard a few questions and then told the captain and the major to sign Howard up.

On the way back to the Civilian Personnel Office, Howard found a U.S. Army library soldiers could use. He went in, found a book on accounting, and did a little brushing up on his high school accounting. He then went back and finished up with Vincent before returning to Salzburg to retrieve the few personal belongings he hadn’t already shipped to the States. Ten days later, he returned to Vienna where he received his Honorable Discharge from the Army and took his new oath as a civilian employee of USFA (United States Forces, Austria). So began Howard’s amazing fifty-year career working as a civilian for the U.S. Army in Europe.

Although Howard began as the Assistant to the Class VI Officer, that didn’t last long because after a month or two, the captain who was the Class VI Officer earned enough points to return to the States, making Howard the Class VI Officer. Two months later, the major in charge of budgeting also became eligible to return to the States. Howard’s boss gave him just three weeks to learn the job of the Budget Officer for Army Special Services, which, inter alia, included the entertainment branch. Eventually, Howard took on additional responsibilities on the entertainment side of Special Services, starting with publishing posters about upcoming events and then moving into event planning and execution. Howard loved his work because his entire focus was helping U.S. soldiers and their families enjoy life in Austria.

Howard’s entertainment branch responsibilities in Austria, and later in Italy at Livorno/Pisa (where a U.S. Army missile command and Airborne Team were established), followed by Verona and Vicenza, allowed him to host and interact with lots of famous entertainers who came to Europe to perform for the troops. Some of the people and shows he worked with included Bob Hope, Orson Wells, Cab Calloway, Joseph Cotton, Minnie Pearl, Red Foley, Little Jimmy Dickens, Eli Wallach, Jack Palance, Primo Canera, and Olivia de Havilland. Just as important, he worked to educate the Austrian people about American culture. For years they had been told by the Nazis that Americans were crude and unsophisticated, so Howard worked with the USO to introduce them to American music and musical theater. The first musical they brought over was Kiss Me Kate, followed by the American opera Porgy and Bess, which starred classically trained African American singers, including Cab Calloway as Sportin’ Life. The audiences loved the shows and the opportunity to see and meet the American stars, helping reverse the harmful effects of years of Nazi propaganda, especially against African Americans.

Although Howard had too many interactions with celebrities to count, three warrant special mention. After years of intense negotiations, the Four Powers governing Austria agreed to leave the country and return control to an Austrian government. The event would be marked by a lavish ceremony and parade in the heart of Vienna, featuring military bands and troops from the United States, the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and France. Orson Wells, who had previously filmed The Third Man in Vienna, asked to attend the ceremony. Howard was selected as his escort, so he attended the ceremony as a VIP with Orson Wells and a translator. Howard still has the thank-you letter he received from Orson Wells.

The second event occurred in Italy when Olivia de Havilland, a famous actress who received an Oscar nomination for her role as Melanie Hamilton in Gone with the Wind, came through to visit the troops stationed there. Howard hosted her in Verona and, because she’d played Juliet in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet on Broadway, arranged for her to visit Juliet’s balcony in Verona. When she went out on the balcony, Howard presented her with roses. Olivia de Havilland loved the event and autographed a photo of her for Howard in return.

The third event involved Cab Calloway, one of Howard’s favorite musicians. He’d loved Cab Calloway’s music since the 1930s and the days of Cab’s hit song Hi-De-Ho. In fact, when he was sixteen, he’d taken a long train ride by himself to watch two of Cab Calloway’s live shows. When Cab visited Vienna to star in Porgy and Bess, Howard asked him after one of the shows if he would be interested in visiting soldiers and patients and their families at the Army hospital. Cab said he would, and the troops loved him. Afterwards, Howard asked Cab if there was anything he could do for him and Cab asked if he could get him a reflex camera, which was extremely hard to find. Howard told him he would check and went to the PX manager and said he needed a reflex camera for Cab Calloway. The PX manager said he didn’t have one, but instructed Howard to come back the next day. When Howard returned, the manager produced a reflex camera, which Howard delivered to Cab and Cab reimbursed him for. Years later, after Cab Calloway had passed, Cab’s daughter, Chris, brought a touring version of her late father’s band to Naples, Florida, where Howard was living in retirement. After the show, Howard found Chris and told her the story about her father and the reflex camera. After hearing the story, Chris signed a program for Howard: “In memory of Cabell Calloway, My Dad.” Howard was extremely happy to learn the source of Cab’s nickname. Originally, he thought Cab must have started out his career as a part-time cabbie and a part-time musician.

Howard met one additional star while he was in Austria – a young woman named Dorothy who, after serving in the Marine Corps, had been accepted into the U.S. Foreign Service and assigned to the U.S. Embassy in Vienna. They were happily married for 68 years and traveled all over Europe together before Howard retired in 1994 from SETAF (the Southern European Task Force) in Vicenza, Italy. They finally settled into retirement, wintering in Naples, Florida, with good friends they met in Europe, and spending the summers in the Denver area where Dorothy’s family lived. Sadly, Dorothy passed away in 2019 and is interred at the Fort Logan National Cemetery. Howard was very proud of the beautiful U.S. Marine Corps ceremony held in Dorothy’s honor, which was attended by many friends and family members.

Howard’s military and government civilian awards include the European African Mediterranean War Medal, the American Theater Ribbon, the World War II Victory Medal for participation in the Rhineland Campaign and Central Europe Campaign, the Department of the Army Civilian Meritorious Service Award, and the first U.S. Army Adjutant General White Plume Award in the European Theater. Howard received the White Plume Award for his dedication to the morale and welfare of the soldiers and their families in Austria and Italy, and that of the “atomic” artillery troops stationed in remote areas of Greece and Turkey during the Cold War (including in Erzurum, Turkey, reportedly the closest U.S. military base to Russia at the time).

Howard’s retirement from the Army was not the end of his community service, it was just the beginning. Since turning 90, he’s created the concept of the “Over 90 Charitable Gift Annuity Plan”, allowing charities to pay significantly higher rates of return on charitable gift annuities. Howard describes the Over 90 Annuities as a “Win-Win-Wow”, because the donor wins by getting a higher rate of return on their annuity for the rest of his or her life, the charity wins because they get a donation they likely would not have received otherwise, and the annuity manager wins because they were successful in getting the plan implemented. At 97 years young, Howard continues to help numerous charities implement the “Over 90 Charitable Gift Annuity Gift Plan.”

Given the many adventures Howard experienced with the Army over his long career, Howard recommends young people today consider service in the military. He notes not only is it a patriotic thing to do, but it also provides an opportunity to see the world, meet new people, earn good pay, and take advantage of free educational opportunities for undergraduate and graduate degrees.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Staff Sergeant Howard Berger for his long and distinguished career with the Army, first as a soldier and then as a civilian employee of Army Special Services. For over fifty years, his service as a civilian helped bring smiles to the faces of tens of thousands of soldiers and their families. He dedicated his entire adult life to our country, and for that we are eternally grateful. We wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Howard’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

February 26, 2022 @ 10:23 AM

By chance, I happened to meet Howard Berger twice, here in Colorado. Both times, I introduced myself to him, as a Board Member / Videographer of the Colorado Eighth Air Force Historical Society. He graciously spent time with me, sharing many of the stories you documented in your article. I feel so fortunate to have met such an extraordinary man that dedicated his life to serving our country and aiding other Servicemen and their families for over 50+ years! I was also quite impressed by his clarity and vivid recollections that he shared! Mr. Berger held my arm, as we walked over to his car last night. At a youthful age of 99, he then drove off alone, into the night…. and what a night it was! Thank you Mr. Berger! – Regards, Mr. Lynn Cooper, Jr.

February 27, 2022 @ 7:37 AM

Lynn – Thanks for taking the time to read Howard’s story and for leaving your comment. Howard is an amazing person and I am so glad our paths crossed. He has a gift of making you feel like a lifelong friend the moment you meet him. V/r, Dave Grogan

March 3, 2024 @ 1:32 PM

I just met Howard and he is adorable. We talked about my WWII dad, Brooklyn, etc.

Want to send him my dad’s autobiography, etc. I feel like I just had a “visit” from my dad.

March 7, 2024 @ 1:20 PM

Nora, Thanks for reading Howard’s story!

February 20, 2025 @ 11:04 PM

I was lucky enough to see my Uncle Howard and Aunt Dorothy once a year when they came to the States for a family reunion and a yearly checkup by American doctors. It never failed that he would give all the kids a brand new one dollar bill. He would challenge you as well! Don’t say yeah only say yes for the day and he would give you double the $!!! We all failed, but it did give us better insight to how we should speak! Then the teen years hit and it was yes sir uncle Howard sir. That’s when the yes instead of yeah dollar stopped, but then everyone got a two dollar bill. Nothing but fond memories!

February 21, 2025 @ 10:00 AM

Brian – I’m glad you got to read your uncle’s story – and thanks for the additional details about this wonderful man!

V/r,

Dave Grogan

February 21, 2025 @ 10:20 AM

I met Howard at OPH in Denver back in January. Now 102 he still has wit, wisdom, and grace. Such a kind person. What a memory he has! I really enjoyed talking with him and enjoyed his story.

February 26, 2025 @ 11:11 AM

Karen, I’m so glad you got to meet him and that you enjoyed his story. He is quite a man!

V/r,

Dave Grogan

March 16, 2025 @ 4:07 PM

Had the tremendous pleasure and honor to meet SSGT Berger on 11 March 2025 at Castle Rock, CO recognition assembly by the Douglas County Commissioners. I attended with my American Legion Harry C. Miller Post 1187 members. In the impromptu reception line in the hall outside the event, I got to thank him and palm him my Post Challenge Coin and my Legion business card. In testament to his gentlemanly manner and an etiquette some may consider lost in our times, he phoned me the very next evening to thank me. We chatted for a bit and he told me about this interview piece. I was/am flattered, further honored, that he took time to call. I’m grateful to have read this wonderful account of his life and career.

I’ll be sharing it with my Post.

Thank you sir,

BZ,

V/r,

March 16, 2025 @ 7:54 PM

Christopher – Thanks for reading Howard’s story and passing along your encounters with him. As you state, Howard is a true gentleman! I also appreciate you sharing his story with your post.

V/r,

Dave Grogan

May 28, 2025 @ 12:31 PM

It’s heartwarming to read that Howard Berger’s best friend Harold Marin is so fondly remembered. Harold Marin or as we called him uncle Harold was the uncle that I never had the good fortune to meet. All I knew was my father spoke glowingly of him family and the whole family was brokenhearted Upon his passing. From most of us, he was just a name that unfortunately was killed in World War II. Thank you, Howard Berger.

May 29, 2025 @ 2:16 AM

Thank you for reading Howard’s story. I am so glad you learned from Howard how much Howard cared about him.

V/r,

Dave Grogan