AD3 Ignacio Rodriguez, U.S. Navy – Hunting Hurricanes and Protecting Pilots

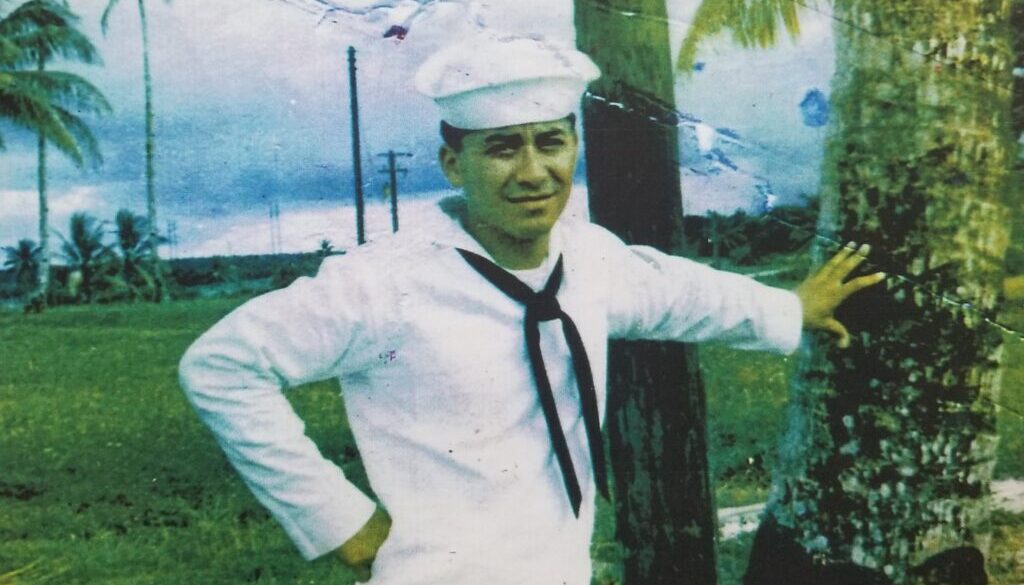

Those who come to America seeking a better life have a long and distinguished history of serving our country. Beginning with the Revolutionary War and continuing in every war since, immigrants have served in every branch of our Armed Forces, willingly putting their lives on the line for their adopted home. Aviation Machinist’s Mate Third Class Ignacio Rodriguez continued that proud tradition, enlisting in the U.S. Navy in 1964. He flew as an aircrewman on EC-121 Super Constellations hunting hurricanes in the skies over the Western Pacific and operating out of Da Nang and Chu Lai during the Vietnam War. He earned his U.S. citizenship the hard way – by serving our country during time of war. This is his story.

Ignacio was born in Tanhuato, a small town in the state of Michoacán, Mexico. He lived with his mother, his two brothers, and his three sisters on their family farm, while his father worked in the steel mills in Chicago to earn money for the family. By the mid 1950s, his father had grown weary of the long trips to Mexico to visit his family and the even longer periods of separation they had to endure. So, when Ignacio was around ten years old, his father brought the entire family to the southeast side of Chicago to live with him permanently.

The family’s living arrangements were typical of the many Mexican, Serbian, Croatian, and Polish immigrants settling in Chicago’s southeast side. They moved into Ignacio’s aunt’s house, making for crowded living conditions. The men left the house early each morning, heading to their jobs at U.S. Steel. They worked hard and earned enough to provide for their families and live a middle-class life, but they were far from rich. Still, it was better than the life they had in Mexico, so they persevered, including with the requirements that they re-register as immigrants every year to maintain their legal status.

At first, the transition to America proved difficult for Ignacio. Although he had been in the third grade in Mexico, he was put into a remedial education class because he did not speak English. When the teacher saw how advanced he was in mathematics relative to the other children, including reciting his multiplication tables through twelve times twelve, she knew he didn’t belong there. Still, he had to learn English to advance, so his parents purchased books that helped him read, write, and learn to speak English, and made him practice with the books every day until he became fluent in his new language.

Ignacio’s parents also made sure he remained connected to his Mexican heritage. They still owned their farm in Tanhuato, where they raised cattle and horses and grew corn. They took Ignacio and his siblings back to Tanhuato every summer to work on the farm and maintain it. They saw the farm as a safety valve in case their American experiment ever failed. Sometimes, this meant staying in Mexico through the fall and having the children continue school there. Although this interrupted Ignacio’s schooling in the United States, it preserved his fluency in Spanish, making him completely bilingual.

When it came time for high school, Ignacio attended Chicago Vocational High School. He did well in school, although growing up in Chicago’s southeast side was tough. His neighborhood was very diverse, with people primarily from Mexico, Croatia, and Serbia, and Ignacio got along well with everyone. However, if he and his friends strayed from their neighborhood, things could be dangerous. He made it through, though, and as graduation neared, Ignacio’s father asked him what his career plans were. Having enjoyed high school, Ignacio responded he would like to pursue engineering. Then, one week before the graduation ceremony, Ignacio’s father was killed by an Illinois Central Railroad train when he was on his way home from a double shift at the steel mill.

Ignacio’s father’s death put the family into a tailspin. His mother was devastated, not only because she had lost her husband, but also because he was the family’s sole breadwinner. Normally, responsibility for the family would have shifted to Ignacio’s older brother, but he was in the Army and could not come home. Ignacio was next in line, but he had recently received his draft notice and had to report for duty in June after graduating from high school. As he had no choice, and the money he earned would help his mother, he reported as directed, just as the conflict in Vietnam was getting ready to turn into a full-scale American war.

Ignacio reported for the draft in June 1964 with a manila envelope containing his draft notice. It looked initially like he might be inducted into the Marines, but as he waited in line, he was approached by a Navy recruiter who asked him to take an aptitude test. Ignacio scored so high on the test, thanks to the education and training he received at Chicago Vocational High School, that the Navy recruiter guaranteed him in writing if he enlisted for six years, he would receive two years of nuclear power training and then serve on nuclear submarines for the remaining four years of his enlistment. The recruiter also promised him that immediately upon his discharge from the Navy, he would be swept up by Westinghouse to work in a nuclear power plant working for big money.

Ignacio was sold and he signed the enlistment contract on the spot. After swearing Ignacio in, the recruiter gave Ignacio the option of reporting for active duty later in the year, an option Ignacio appreciated because it would give him time to help his mother get back on her feet after his father’s death. He chose October 1964 as his report date and then returned home to get his family’s affairs in order.

In October, Ignacio reported for boot camp at Naval Training Center Great Lakes, just north of Chicago. He found boot camp challenging not because he couldn’t do what was required, but because he was “stubborn” and didn’t like to take orders. Despite this, his company commander saw Ignacio had the potential to be a strong leader, so he called Ignacio aside and told him he was choosing him to be the Recruit Petty Officer, or RPO. Ignacio asked what that was, and the company commander told him, “When I’m not here, you make sure everyone stays in line.” Then he added, “If they step out of line, you’ll pay for it.”

That was all the guidance Ignacio needed. He told the other recruits in his company, “If I’m going to get punished, so will everyone else. So, let’s get this done together or we’ll all end up suffering.” It worked and the company pulled together and made it through to graduation. Not only that, but they also earned the right to carry the efficiency flag, having achieved the highest overall average in all the areas of recruit competition.

Graduation proved bittersweet for Ignacio. Although he had successfully completed the Navy’s rigorous training and was now officially a Navy Airman (E-3), after the graduation parade, all the other new Navy sailors celebrated with their families and friends. Ignacio had no one to celebrate with – no one from his family had made the short trek from Chicago’s southeast side to the Naval Training Center on the north side. Instead, Ignacio sat alone with his sea bag, waiting for transportation to his follow-on training. Moreover, the follow-on training was not what he had been promised. Because he was not yet a U.S. citizen, he did not qualify for nuclear power school. Instead, he received his second choice – working on aircraft as an Aviation Machinist’s Mate, which the Navy abbreviated as “AD”.

In January 1965, Ignacio departed Recruit Training Center Great Lakes, boarded a train, and headed for Naval Air Station Memphis in Millington, Tennessee, to attend Aviation Machinist’s Mate “A” school. There he learned to perform routine aircraft maintenance, to prepare aircraft for flight, and to assist with handling aircraft on the ground. After completing his training at Millington, he transferred to Naval Air Station Corpus Christi in Texas for advanced Aviation Machinist’s Mate training, where he learned to work on multi-engine aircraft, as well as on powerful single-engine tactical aircraft like the A-1E Skyraider.

Upon completion of the training in Corpus Christi in late 1965, he and six other newly qualified Aviation Machinist’s Mates received orders for their first permanent duty station in Alaska. Ignacio was unhappy about the orders and asked why he was being sent so far north. He was told they needed six airmen in Alaska and since he was from Chicago, they thought he would enjoy the cold weather. Ignacio explained that was definitely not the case, especially since he had grown up in the sub-tropical heat of Michoacán in southwest Mexico. Armed with this new information, the detailers served up a much more acceptable set of orders. Ignacio was headed to the tropical island of Guam in the western Pacific Ocean.

Ignacio reported to Airborne Early Warning Squadron ONE (VW-1) at Naval Air Station Agana, Guam, in early 1966. The squadron flew the EC-121 “Warning Star”, the military version of Lockheed’s successful four-engine civilian airliner, the Super Constellation. The squadron’s mission was to search the skies of the Pacific for potential Soviet threats, and to fly weather reconnaissance missions tracking typhoons, earning them the designation as “Hurricane Hunters”.

When Ignacio first arrived, he was responsible for fueling the giant EC-121 aircraft, for checking their hydraulics systems for leaks, and for general aircraft maintenance, including monitoring repair logs to ensure scheduled maintenance was conducted on time. If planes were to be deployed when the scheduled maintenance came due, Ignacio would ensure the necessary parts were on hand to conduct the maintenance early rather than have a plane be designated as non-mission capable while deployed far from home. Once Ignacio and the other maintenance personnel completed the necessary maintenance, the Quality Control Chief checked their work to make sure it had been done correctly. Only then would the aircraft commander sign off on the repairs because the safety of the aircrew was at stake every time the airplane took off.

Ignacio soon learned unless he became aircrew qualified, he would spend his entire enlistment on the ground in Guam. However, if he qualified as an aircrew member, he would get to fly on the squadron’s missions as part of the planes’ aircrew. Accordingly, he applied for and was accepted into flight crew training. Topping that, he also applied for and became a U.S. citizen. He wore his Navy uniform during the ceremony, which the judge conducting the ceremony noted as he described what it meant to be a U.S. citizen.

Flight crew training meant going to Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) School in San Diego, California. There Ignacio learned what to expect if he was ever captured by enemy forces. He was treated like a POW, blindfolded, interrogated, allowed little to no sleep, and punished for made up infractions. While all this was going on, Ignacio and the other trainees had to avoid providing information to their captors that might prove harmful to their shipmates or the United States. The training felt real and was hard to endure, but Ignacio understood it was for his own good should the unthinkable ever occur.

After SERE School, Ignacio was sent to the Philippines for Jungle Environment Survival Training and then to Okinawa for Sea Survival Training. After completing all this training, he returned to Guam and joined Aircrew 6, one of VW-1’s twelve aircrews, each of which had approximately thirty-two men assigned. Occasionally, he would fly a mission with another aircrew if they were short a man. Some missions took off and landed in Guam, while others involved interim stops at airfields across the Pacific, including in Okinawa, Taiwan, Wake Island, Midway, and Thailand. When the plane landed at one of those destinations, Ignacio was responsible for making sure the plane was fueled and ready to go for the next leg of the mission.

Still wanting to do more, Ignacio qualified as an EC-121 Crew Chief. Everyone had a job to do on a mission, from flying the plane to monitoring radar and other electronics equipment in flight. The Crew Chief’s job was to make sure every crewmember had what they needed to get their job done. This could mean anything from getting food for someone who could not leave their station to covering for someone at a radar screen while they stepped away.

Two types of missions proved particularly dicey. When Ignacio’s plane was surveying a typhoon, it meant flying through the turbulent feeder bands into the eye of the storm, recording storm data, and then transmitting it to fleet units around the Pacific before making their way home. During such missions, the rides could be very rough, battering the aircraft and the crew for the hours it took to enter and exit the storm. During one such flight, Ignacio’s plane was tasked with a Search and Rescue (SAR) mission, to see if they could locate an Okinawan fishing boat lost somewhere in the storm. Miraculously, they found the boat in the eye of the storm and helped guide it back to safety. In August 1966 alone, Ignacio’s crew tracked six named storms.

The other dangerous type of mission deployed Ignacio and Aircrew 6 into the middle of the Vietnam War. On such deployments, Ignacio’s plane would operate out of either Da Nang or Chu Lai in the Republic of South Vietnam. Because the big planes were obvious high-value targets for Viet Cong mortar and rocket attacks, immediately after they landed Ignacio began refueling and prepping the plane so it could take off on a moment’s notice. Missions originating in Da Nang and Chu Lai typically began at 5:00 p.m. and lasted all night, with the EC-121 flying at 25,000 feet on Yankee Station over the Gulf of Tonkin. The plane’s purpose was to track U.S. bomber and attack aircraft flying over North and South Vietnam and to help them avoid North Vietnamese air defenses, including surface-to-air missiles (SAMs). Because U.S. carrier aircraft returned to their aircraft carriers at sea after an attack in North Vietnam, they headed away from the coast observing strict radio silence. If the radar observers on Ignacio’s plane could not confirm whether they were a U.S. aircraft or a North Vietnamese fighter heading towards them, the plane would have to take evasive action by diving from 25,000 feet to just above sea level until radio contact confirmed the approaching aircraft was friendly. These were tense times for everyone on board.

Not all of Aircrew 6’s missions were to Vietnam, allowing some time for fun. In fact, the crew, which consisted mainly of young men from seventeen into their early twenties, always carried their bathing suits in their flight bags because their destinations often included locations near pristine beaches. When crewmembers showed photos of the crew having a good time at the beach on Wake Island, others thought their lifestyle looked pretty good. Still, they were on the go all the time and the beach forays offered a brief escape from the serious business they were so often engaged in.

Ignacio continued flying with VW-1 until October 1968. At that point, he either had to reenlist or be discharged back to civilian life. He initially intended to reenlist as he thought he could get a follow-on assignment in Rota, Spain. However, his command made it clear, if he reenlisted, he would stay in Guam because he was too experienced to let go. Ignacio didn’t want that, not because he didn’t love what he was doing – he did. But his job at the squadron had become routine, with every day feeling like the day before. So, in October 1968, Ignacio was honorably discharged from the Navy and he returned to civilian life in Chicago.

The transition back to civilian life proved difficult. His family and friends were not supportive of his experience in the Vietnam War and none of them wanted to talk to him about it. Ignacio did want to talk, so he started getting together with a group of veterans from his neighborhood at a local park to discuss their experiences. This turned into a lifelong involvement in veterans’ organizations. He also earned a little extra spending money by maintaining his flight status through the Naval Reserves at Naval Air Station Glenview, Chanute Air Force Base, and Grissom Air Force Base, but the Reserve activities at these facilities soon closed leaving Ignacio with no alternatives.

The part of the transition that did go smoothly was Ignacio’s entrance into the civilian workforce. He initially took a job with Delta Airlines at O’Hare International Airport, but after four years of working on the flightline during Chicago’s grueling winters, he took a position with the City of Chicago maintaining vehicles and snow equipment. He retired from that position after thirty-five years.

Two other events took place in the 1980s that set Ignacio on a steady course. First, in 1985, the Windy City Veterans Association decided to hold what they hoped would be the biggest ever parade in honor of Vietnam veterans. Ignacio jumped into the planning effort with both feet, working on the committee that sent letters to veterans’ organizations across the country, and even to allied veterans in Australia. On the night before the parade, Ignacio and other members of the Windy City Veterans Association set out markers at Chicago’s Navy Pier to help organize the marchers. The next day, June 13, 1986, as the marchers began to assemble, Ignacio could not believe his eyes. Tens of thousands of Vietnam veterans arrived to participate from as far away as Australia, marching from Navy Pier, along Wacker Drive, down LaSalle Street, and on to Grant Park. An estimated 500,000 people lined the parade route, cheering the veterans on as they passed along the same streets where anti-war protests echoed less than two decades before. Construction workers and Chicago Policemen, many of whom had also served, joined the ranks of the marchers as the parade passed their worksites. Finally, all the Vietnam veterans came together in Grant Park, reuniting with friends, sharing experiences, and remembering lost comrades.

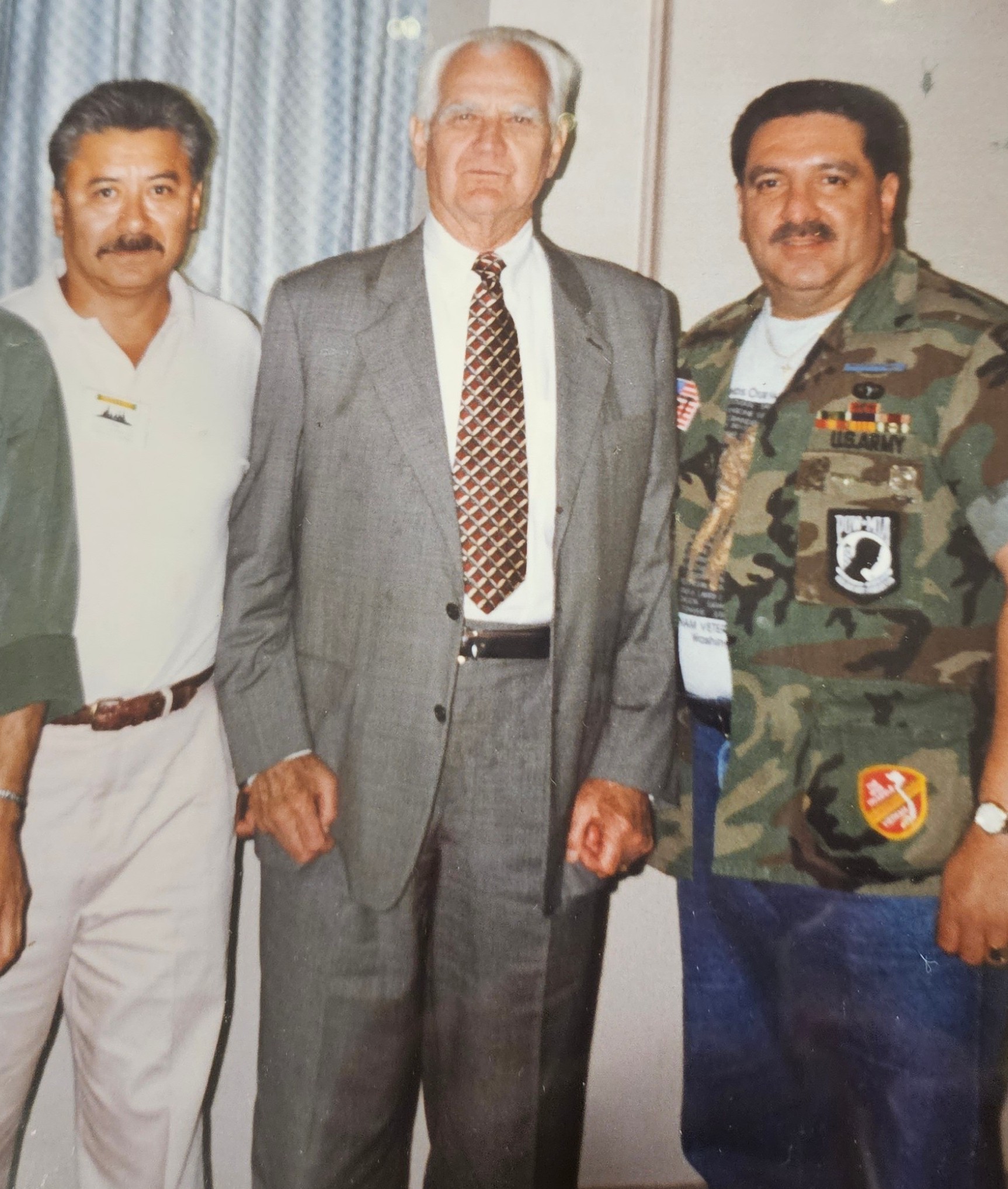

Ignacio marched in the parade carrying a POW flag on a bamboo pole. As he did, Medal of Honor recipient Sammy Lee Davis from Indiana took the flag and began waving it around. Ignacio met Sammy as a result, and they became lifelong friends. In all, the parade proved an emotional experience for Ignacio and many others, and something Ignacio is immensely proud to have been a part of.

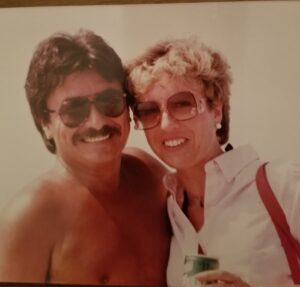

Two years after the Chicago Veterans Parade, the second significant event of the decade occurred: Ignacio married his wife, Joyce. They have now been married over thirty-five years and are living happily together in retirement.

Ignacio continues to be heavily involved with his fellow veterans. He belongs to the Windy City Veterans Association, as well as American Legion Post 845 in Schererville, Indiana; Vietnam Veterans of America Chapter 153; Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) Post 6448 in Dyer, Indiana; and the Howard County Vietnam Veterans Organization in Kokomo, Indiana. And, because he suffers from the effects of exposure to Agent Orange during his time in Vietnam, he is a member of the Disabled American Veterans of America Chapter 17 in Hammond, Indiana.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Aviation Machinist’s Mate Third Class Ignacio Rodriguez for his distinguished service in the U.S. Navy. Even before he became a U.S. citizen, he answered his new country’s call, flying airborne early warning missions in the Vietnam War and surveillance and weather missions across the Pacific Ocean. Since then, he has spent his life welcoming veterans home and serving his community through multiple veterans’ organizations. We thank him for his lifetime of service and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Ignacio’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.