Private First Class Oscar Green, U.S. Army – Fighting in Europe to Save His Brother

True courage is rare. It only shows itself when a person is tested. For that reason, you can’t look at someone or listen to what they say about themselves to predict if they will be courageous. In fact, many courageous people won’t talk about their deeds because they don’t consider what they did anything special. They see their actions as simply doing their jobs. That’s why you can walk down the streets of New York City, sit in a diner in Chicago, talk to a farmer in Texas, or meet a laborer repairing a roof in California, and not realize you are in the presence of someone great. For example, who would have thought a twenty-year-old truck driver from Waynesburg, Kentucky, would have the courage to walk to death’s doorstep on battlefields in Europe, then return to his humble Kentucky surroundings as if his encounters with death never happened. That’s what Private First Class Oscar W. Green did in the waning days of World War II. This is his story, as told through his grandson, Mike Reed, and family friend, Dan Klare.

Oscar was born to John and Lilly Green on May 20, 1923, in the tiny town of Waynesburg, located in central Kentucky about sixty miles south of Lexington. He was the eighth of thirteen brothers and sisters who worked on the family farm. His father also operated a blacksmith shop, and persons from as far away as Lexington would come to get work done. Oscar attended school through the fourth grade, but quit school in 1935 during the middle of the Great Depression to work at home with his family.

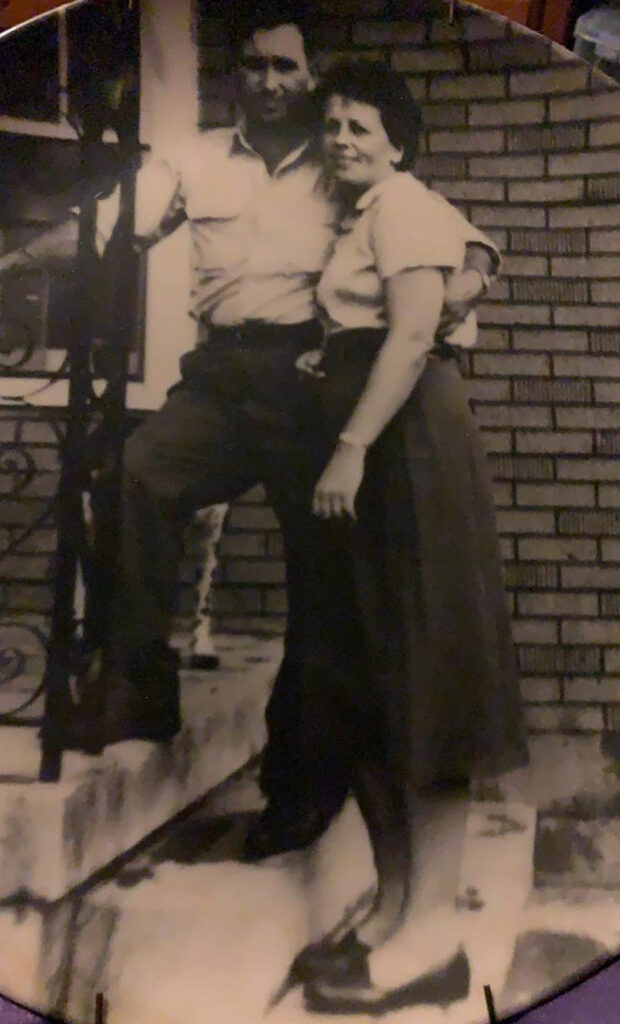

Although the Depression made life hard, Oscar found time for activities other than work. When he was seventeen, he fell in love with Mary Josephine Coker, a fifteen-year-old girl from nearby King’s Mountain. Oscar’s family, and especially his mother, didn’t approve of the relationship because Mary was literally from the other side of the tracks. A railroad ran through the town and Mary’s side was more industrial than Oscar’s family’s rural surroundings, so Oscar’s mother did not consider Mary good enough for Oscar. Oscar’s family was devout Methodist while Mary’s was devout Baptist, further adding to the divide. Oscar saw things differently than his mother, though, and asked Mary to be his wife. Unlike Oscar’s mom, Mary’s mother approved of the marriage and not only signed to allow her daughter to marry at age fifteen, but also served as a witness for the ceremony in Waynesburg in January 1942.

Oscar and Mary began their life together living in King’s Mountain with Mary’s family. Oscar worked throughout 1942 and into early 1943 as a cook in Highland, Kentucky. Mary gave birth to their first daughter, Patsy, in February 1943, adding another mouth to feed to the family. Oscar changed jobs soon thereafter and drove a light truck for the Lincoln Lumber Company for the last seven months of the year. Then Oscar made a decision that would forever impact his family.

By then, World War II raged throughout Europe and across the Pacific, directly affecting Oscar’s family. Oscar’s older brother, James, was already serving in the Army and fighting the Japanese. Oscar felt like he needed to enlist, too, to help bring his brother home. Oscar’s daughter was almost one year old, and he felt he could leave Mary and Patsy to join the war effort. By heading off to fight, Oscar believed he was doing his part to bring the war to an end, which meant his brother would be able to come home. With his mind set, he went to an Army recruiting station on January 8, 1944, and signed on the dotted line. Three weeks later, on January 29, Oscar took the oath of enlistment and entered active duty in the U.S. Army.

Oscar reported to “boot camp” at Camp Wheeler near Macon, Georgia. The Army used the camp to convert citizens into soldiers and, instead of training them to be part of a new unit that would deploy intact to fight the enemy, trained them to be replacements to fit into existing units that had sustained casualties and needed new soldiers to fill their ranks. Oscar complained in a letter to Mary that the bugs were “eating him up” and he couldn’t wait to get out of there. Once he graduated from boot camp in June, Mary left Patsy at home with her mother and visited Oscar in Georgia. It was the last time they would be together before Oscar shipped off for the war.

Boot camp wasn’t the end of Oscar’s training at Camp Wheeler. He also received his advanced training in infantry skills at the camp. This advanced training was crucial because Oscar would be a replacement soldier for the 44th Infantry Division, a National Guard Division which was already finalizing preparations at Camp Myles Standish in Massachusetts to sail to Cherbourg, France, for action against the Germans. The 44th Infantry Division left the port of Boston on September 5, 1944, and landed in France on September 15.

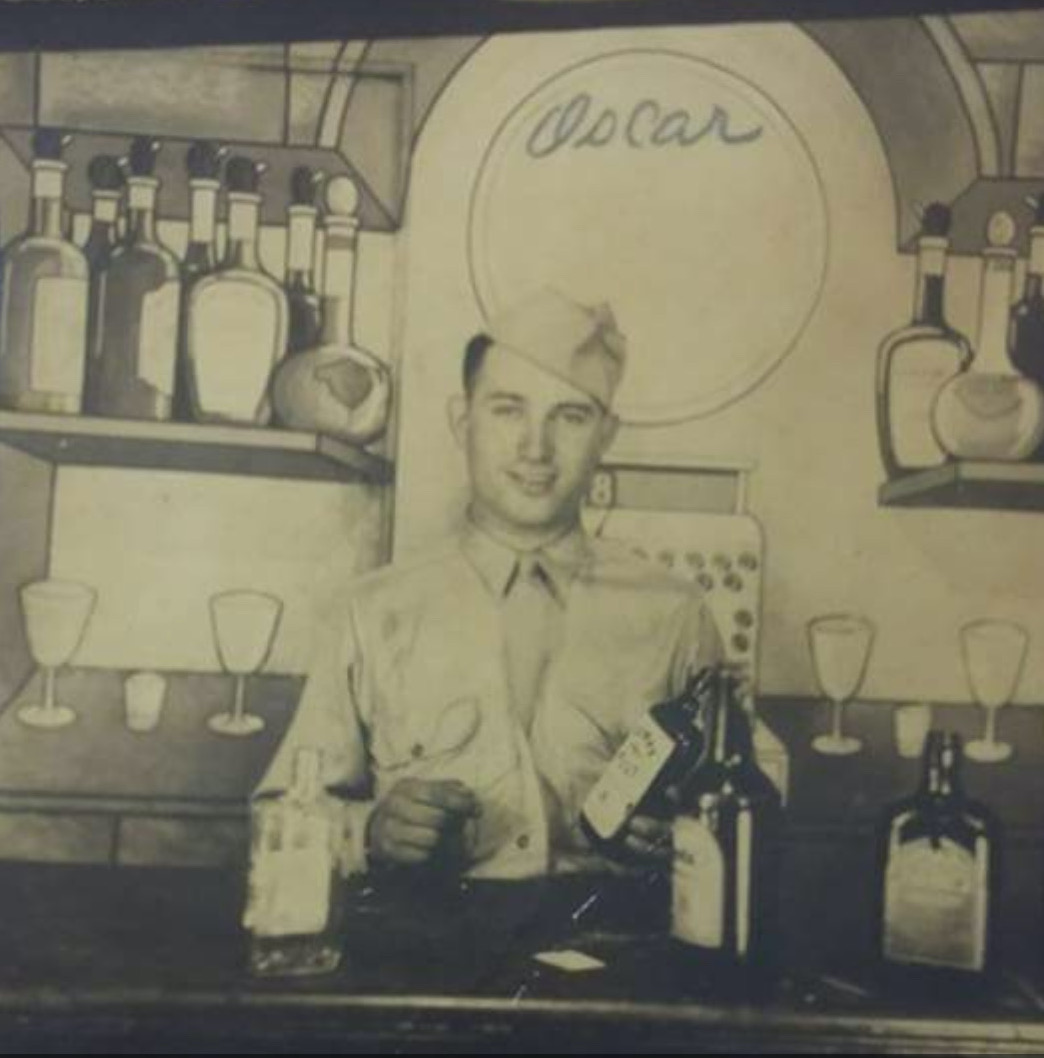

Because Oscar was still in the replacement training pipeline when the 44th Infantry Division departed, he did not sail to Europe with the Division. In fact, during the month of September 1944, he was in Fort Meade, Maryland, where the Army trained cooks and bakers. While he was there, he received a letter from Mary responding to a picture he had sent her showing him posing with a bottle of whiskey behind a bar. The bar appears to be a set used by the photographer to take pictures of soldiers. The backdrop is a drawing of the wall behind the bar, with Oscar’s name written in big letters above the image of a cash register. Mary, a staunch Baptist opposed to consuming alcohol, did not like what she saw. On September 26, 1944, she wrote Oscar a letter telling him just that. She said, “Well, I’m sorry you have to do such things since you have a daughter at home to think of and knowing that you may be soon facing the battlefield and you are unprepared to die and go out into eternity unprepared to meet thy God.” Although Mary was just eighteen, her letter made it clear she understood the gravity of what her husband was about to embark upon. She also made it clear she and Patsy wanted him to come back home alive.

Given that Oscar followed in the footsteps of the 44th Infantry Division, he likely staged at Camp Myles Standish awaiting a ship that would carry him to France. He set sail from Boston in October 1944 and arrived in France on October 26, two days after the 44th Infantry Division saw its first action 475 miles to the east in the Vosges Mountains. Oscar joined the Division in November, as it was fighting through the mountains on its way to liberate the city of Strasbourg, France, together with the French 2nd Armored Division. He was assigned to Company K of the 3rd Battalion, 71st Infantry Regiment—one of three infantry regiments comprising the 44th Infantry Division.

After helping capture and hold the towns of Sarrebourg and Rauwiller, both located about forty-five miles west of Strasbourg, the 71st Infantry Regiment turned northward in December, taking on the Germans defending captured French fortifications on the Maginot Line. The objective, Fort Simserhof, fell to the regiment on December 20 after six days of fighting. Oscar’s 3rd Battalion repositioned to the vicinity of Gros-Rederching, France, on December 23 in response to the German offensive to the north known as the Battle of the Bulge. Oscar’s medical records indicate he was also treated in December for trench foot—a painful condition resulting from having cold, wet feet for too long.

Fighting was heavy in the snow and bitter cold after the first of the year, with the German’s attacking the 71st Infantry Regiment’s position. Company K was right in the thick of it, helping hold back the German advance. After the engagement, Company K and the rest of the 3rd Battalion relocated several times, all the time subject to German mortar and artillery fire. Oscar managed to live through it all unscathed, but on February 15, 1945, his luck ran out near Rimling. As Oscar and the other men in his unit began digging defensive positions, German automatic rifle fire opened up on their right flank, causing the men of Company K to take cover. Oscar’s Silver Star citation tells what happened next:

“Private Green, realizing the danger involved, crawled 75 yards toward the position of the hostile fire when he was hit in the back. Despite his injury, he continued firing at the enemy, accounting for at least two. Running out of ammunition, he returned for more and again moved toward the enemy gun, this time killing another German and forcing the others to withdraw.”

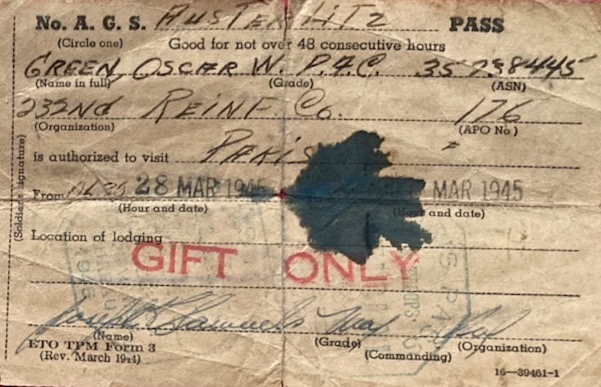

What the citation does not describe is how seriously wounded Oscar was. He was hit by three German machine gun bullets in the shoulder and had to be evacuated from the front. He wrote a letter to Mary and Patsy that same day, or at least dictated one to someone writing for him, and told them how much he loved them. He did not mention being wounded, but told them he wanted to get home to see them. His wounds, however, did not get him sent home. After he was sufficiently recuperated to be returned to duty, he was assigned to the 232nd Reinforcement Company. On March 28, he was given a forty-eight-hour pass to Paris, where he stayed at the Maisons Laffitte, one of several properties designated for soldiers recuperating from their wounds. Not wanting to leave his buddies behind, he returned sometime in April to the 71st Infantry Regiment to pick up the fighting where he left off. This time he was assigned to Company L, which was also part of the 3rd Battalion.

Starting in mid-April, the 71st Infantry Regiment was on the move in Germany, having teamed up with the 772nd Tank Battalion and the 10th Armored Division. After capturing several towns along the way, the 3rd Battalion crossed the Danube River on April 23. Although the timing isn’t clear, Oscar relayed a story to his grandson after the war that early one morning when they were moving through the woods, they smelled coffee and bacon cooking. When they found the source of the smell, it was a German encampment with everyone sleeping except a lone German soldier making coffee and cooking bacon. Oscar’s job was to slip into the camp and eliminate the cook, which he did. Then the rest of the unit sprung on the camp and the Germans surrendered, thinking there were more American attackers than there really were. Oscar took a pocket watch from one of the German soldiers, but that was not all. Whether during this incident or some other at about the same time, he and his fellow soldiers confiscated some gold bars they found with the German soldiers they captured. Oscar said each soldier in his squad tucked away two gold bars and continued on. Oscar later discarded his because they were too heavy to carry together with his rifle and other gear. He lamented after the war that if he’d been able to keep just one of the bars, he never would have had to work again. He did, however, keep the watch he took. The watch is inscribed “Werner Trau of Korbach, Waldeck,” which is in Germany. (Oscar’s grandson would like find Werner Trau’s family, if possible, to learn more about the story behind the watch.)

After crossing the Danube, the 3rd Battalion pushed easterward to establish a bridgehead over the Iller River near the town of Illerieden. When they reached the bridge they were supposed to secure, the Germans blew it up. However, a cable remained between the two ends of the blown bridge and the soldiers began to cross going hand-over-hand. As Oscar prepared to cross the wire, he saw two men in front of him fall in and get swept downstream. Despite carrying his rifle and other gear, he managed to make it across without incident.

With the war with Germany entering its final days, the 71st Infantry Regiment and the 10th Armored Division fought deeper into Germany, until they captured Füssen, which was near the Austrian border. They then fought their way through passes in the Austrian Alps, which had to be cleared of defensive positions and snipers all along the route. When they reached Fern Pass, at an elevation of almost 4,000 feet and in the highest section of the Austrian Alps, the weather was bitter cold and snowing. The road through the pass was cratered to make it impassable and was defended by German heavy artillery. The Germans stalled and battled the 3rd Battalion in the pass all through the night of May 1, with Oscar and the rest of Company L dueling with the Germans in order to dislodge them. The stalemate broke after the 1st Battalion made a treacherous journey around the enemy and came upon the Germans from behind.

The battle at Fern Pass proved catastrophic for Oscar. As he exchanged fire with a German soldier, he felt a bee sting on his left eye and tried to wipe the sweat he felt running from his face. He kept firing and saw the German fall. That was the last thing he remembers because at that point, his position took a direct hit from a German panzerfaust, a high-explosive anti-tank rocket with deadly effects on infantry, as well. This time Oscar’s war was over for good. So was Germany’s, as it surrendered just five days later on May 7, 1945.

A few days after the battle at Fern Pass, Mary received a Western Union telegram indicating Oscar was missing in action. A few weeks later, Army representatives visited her and gave her Oscar’s dog tags. They informed her Oscar was missing and presumed dead. Mary refused to accept their message. She told them, “You’ve only given me his dog tags. Until you show me his body, he’s not dead as far as I am concerned.” She added, “If he is dead, I want him brought back to Kentucky for a proper burial. I don’t want him buried in Europe.”

After the men went away, Mary reached out to the Red Cross for help. They told her she should investigate the “John Doe” soldiers being returned to the United States. Most had face or head wounds so they could not be identified. Each time Mary got word of a group of John Doe soldiers, she checked them out. She went to St. Louis and Kansas City to no avail. Then she learned some John Doe soldiers had arrived from France on June 26, 1945, and were being transported to a hospital in Maryland. As Mary prepared to go see them, Oscar’s mother decided to join her and the two traveled from Kentucky to the hospital by bus. Once they arrived at the ward, Mary heard a man talking and told the attendant, “I hear my husband.” Oscar’s mother called out his name and Oscar answered, triggering his memory for the first time since the panzerfaust blast.

The reunion was both happy and sad. Happy for the obvious reason that Oscar and Mary were reunited, but sad because Oscar had been terribly wounded. The bee sting Oscar felt was a bullet that took away his left eye and part of his left cheek, while the panzerfaust blast had severely injured his left arm, torso, and leg. He told Mary he did not want to go home with her because he was only half the man he had been before the war. Mary would have none of it, declaring he was the man she’d married and he was the man she was taking home. Besides, she had something special to show him. His second daughter, Barbara, who was conceived during Mary’s visit with Oscar after boot camp graduation, had been born while he was in Europe and had never seen her daddy. On top of that, Oscar’s mother now loved Mary dearly because Mary never gave up on Oscar when others said he was dead. She credited Mary with bringing Oscar home to the family.

The road ahead was tough for Oscar. He still had months to recuperate and wouldn’t be discharged until November 23, 1945, after he was fitted with a glass eye in Cleveland, Ohio. He couldn’t work and was given a 100% monthly disability payment. When he returned to Waynesburg, Kentucky, his family rallied around him and five of his brothers built him a house in 1948. Oscar made it a point to be at the worksite every day, which didn’t sit well with someone in the town. They complained he shouldn’t be receiving a disability check if he was at the construction site because that meant he had to be doing some of the work. The result was his monthly disability payment was cut in half. Oscar wanted to challenge it, but was afraid they would take the other half away if he did. He told his family, “If the government thinks they need that money more than I do, they can have it.”

Because of his wounds, it took several years before Oscar was able to work full time again. Handy with mechanical equipment before the war, Oscar took a job with the Gene Triplet Farm Equipment Company of Danville, Kentucky, repairing farm equipment and becoming a skilled mechanic. He later shifted to working on cars, which he did for about fifteen years until he had to retire due to heart issues. Oscar’s grandson remembers seeing Oscar work on cars, often leaning on the car and doing the work with his right hand. Shrapnel continued to work its way to the surface of his skin until it could be removed with a pair of tweezers, and he and Mary kept an ash tray filled with the little slivers of metal as a testament to what he had endured during the war. He also had nightmares for the rest of his life, flashing back to the incessant combat he experienced fighting his way through France, Germany, and Austria.

Despite all of this, Oscar remained in good spirits. He and Mary raised their two daughters and were dedicated to their family. Oscar was particularly close to his grandchildren, all of whom admired him not only for his service during the war, but also for the way he lived his life with quiet dignity. Mike Reed, for example, felt very honored when Oscar agreed to serve as best man in Mike’s wedding. Oscar also lived by the 23rd Psalm because he believed that Psalm had saved his life. When he took the hit from the panzerfaust, a small Bible in his breast pocket absorbed shrapnel that otherwise would have gone into his chest. The shrapnel penetrated through to the 23rd Psalm and stopped there, so he found comfort in the Psalm for the rest of his life. In the end, though, it was a piece of shrapnel lodged in his heart that killed him. Too dangerous to remove, the metal fragment caused five heart attacks, the fifth one killing him on January 30, 1995. His beloved Mary, who never gave up on him, predeceased him in December 1984.

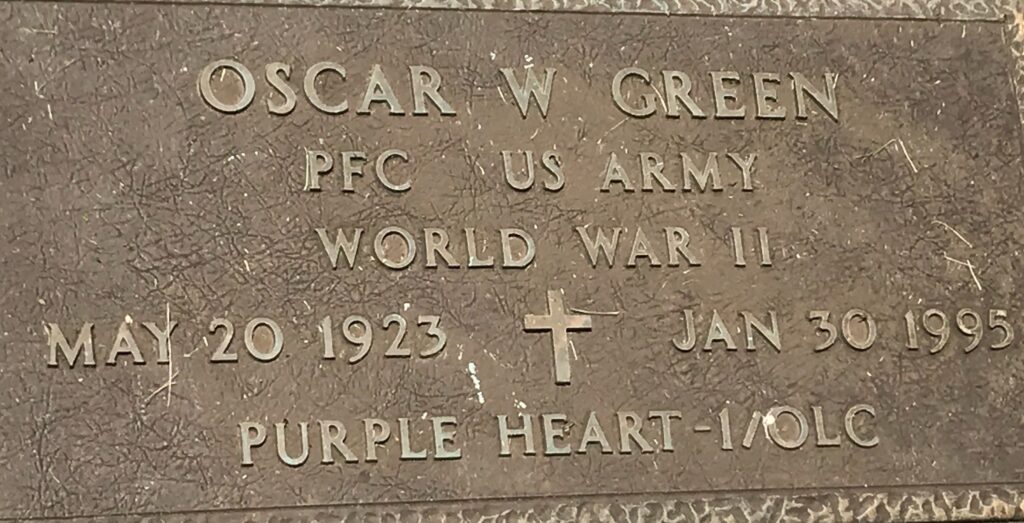

For his service during World War II, Oscar earned the Silver Star, the Bronze Star, the Purple Heart with one Oak Leaf Cluster, the Army Good Conduct Medal, the Army of Occupation Medal with Germany Clasp, the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with two Bronze Service Stars, the World War II Victory Medal, the Combat Infantryman Badge, the Sharpshooter Badge with Rifle Bar, and the Honorable Service Lapel Button WWII.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute the life and service of Private First Class Oscar W. Green, U.S. Army. He endured unimaginable hardships, never asking for anything in return. He enlisted believing he needed to do his part to help the United States and its Allies win the war and bring his brother home. He demonstrated courage under fire and bravery in the face of a determined enemy, and never backed down. Moreover, he continued to demonstrate courage back home, raising his family and inspiring all those around him. This story, coming over twenty-six years after his death, demonstrates the lasting impression and legacy Oscar left behind. Were he here today, we would thank him for his service and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Oscar’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.