Colonel Hank Hoffman, U.S. Air Force (Ret.) – Welcome Home From Vietnam

What do you say to an Air Force pilot who flew 377 combat missions over the course of four different combat tours in Vietnam? How do you say thanks to a man who answered his country’s call and put his life on the line every time his aircraft took off from far away bases in Guam, Japan, Thailand and Vietnam? In Colonel Hank Hoffman’s case, the answer is simple. You shake his hand and extend to him a heartfelt “Welcome home.” Then you listen to what he has to say. This is his story.

Hank grew up in a lower-middle class neighborhood in Detroit. His father was a pilot for Eastern Airlines, but his parents divorced when he was young, so Hank drew inspiration for flying from reading science fiction. He wasn’t just interested in flying airplanes—he wanted to fly in space and be the first person to set foot on Mars. That was a tall order for a boy being raised by a mother with limited means, but he was smart and hard-working, so a door opened for him. As he was entering the seventh grade, he earned a scholarship to the Cranbrook School in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, which was an exclusive boarding school just north of his family’s home. The Cranbrook School prepared him well for his future, but it wasn’t always smooth sailing.

As with most boys, Hank enjoyed sports more than studying. He was an excellent middle distance runner and was the Interstate League champion in the 440-yard dash. He also lettered at soccer. What he did not excel at was memorization, not because he couldn’t, but because he wouldn’t devote time to it if he didn’t see its value. As a result, his studies suffered. Then, at the end of his sophomore year, the headmaster called him to his office and told him his scholarship was being terminated because things had changed. At the time, Hank attributed the change to his failure to reach his full potential. He later learned the changed circumstances were that his mother had re-married and they no longer qualified for a need-based scholarship.

Hank split his junior year between two schools in Detroit, but really missed Cranbrook and wanted to return for his senior year. He begged his mother to find the tuition to send him back and she did, so he graduated from Cranbrook with his friends. He also scored extraordinarily high on his college entrance exam tests, so he was well situated to apply for college.

Although Hank had several partial scholarship opportunities, he really wanted to attend the U.S. Military Academy at West Point where tuition, room, and board would be free subject to him giving the Army six years of his life after graduation. Given his athletic prowess and college entrance exam scores, Hank believed he could get admitted—all he needed was to be nominated by his Congresswoman for a slot. When Hank visited her, she told him she had already made her nomination for West Point, but that she had a nomination available for the brand-new Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs. She said he and the other interested young men would have to take a test and she would give the person scoring highest her nomination. Hank scored the highest by far, but the Congresswoman still gave the nomination to another young man, making Hank an alternate. Hank was still offered admission; however, he vowed never to vote for the Congresswoman because she went back on her word.

Hank’s Air Force adventure began almost immediately after he graduated from Cranbrook School. He reported to the Air Force Academy on June 26, 1959, as part of the fifth class to attend, but the first class to actually live at the Academy for all four years in the newly finished dormitories. While the Academy was new, the military training was not—it was rigorous and nonstop. Hank and the other “doolies”, as the 4th Class cadets are called, soon found themselves running around getting haircuts and uniforms and learning who was in charge.

The next day, Hank’s flight of cadets was awakened at 5:00 a.m., an hour before physical training was supposed to begin, so they could be the first flight to run to “the rock”, a nearby mesa 7,250 feet above sea level. Being in superb shape and having just come off the spring track season, Hank made it to the top, finishing just behind the flight’s first sergeant who orchestrated the run and was captain of the cross country team. Hank went on to be a very successful runner and soccer player for the Academy, repeatedly lettering in both sports. He also graduated 41st out of the 499 cadets comprising the Class of 1963, completing 215 semester hours while still keeping up with his military duties. The famed General Curtiss LeMay, then the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, handed Hank his degree.

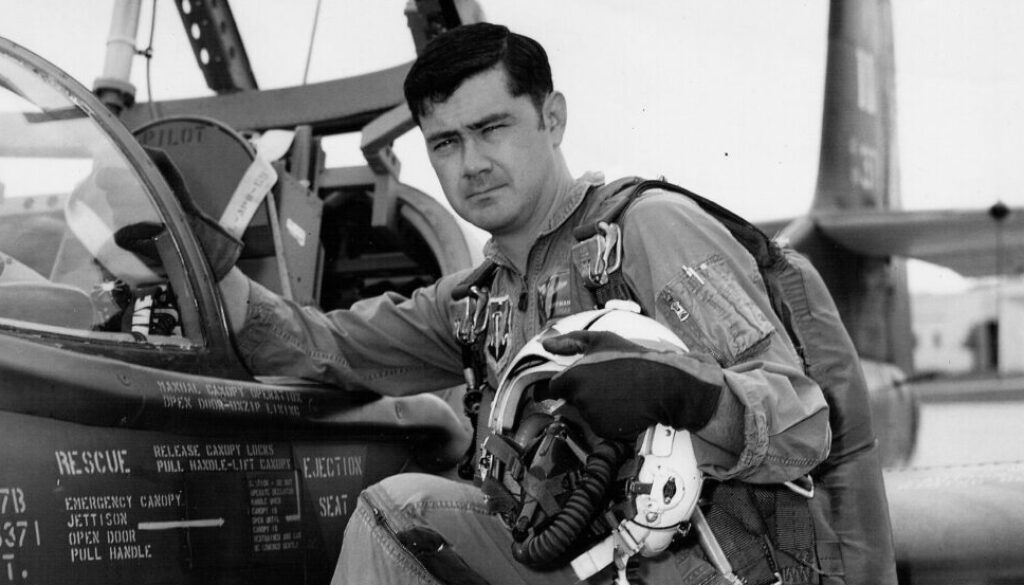

After graduation and a quick visit home, Hank drove his new Ford Galaxy to Williams Air Force Base, located thirty miles southeast of Phoenix, Arizona, for basic pilot training. He trained with a group of German officers who were learning to fly at the U.S. base. He remains friends with them to this day. He spent six months learning the basics in the two-seat T-37, and then transitioned to the new T-38 supersonic jet trainer, which was fun to fly. After graduating from pilot training, he and about sixty percent of the new pilots headed to the Strategic Air Command, or SAC, to learn to fly the B-52 “Stratofortress” or the KC-135 tanker “Stratotanker” (for in-flight refueling). Hank was assigned to B-52s.

The B-52, affectionally known as the BUFF (“Big Ugly Fat Fella” or other expletive), has been in continuous service in the U.S. Air Force since 1955. Originally designed to carry nuclear weapons as part of America’s nuclear triad, it also proved to be a potent conventional weapon. In Vietnam, B-52s were outfitted to carry twenty-four 750-pound bombs externally on their wings, as well as eighty-four 500-pound bombs internally in their bomb bays. That meant it could deliver over 60,000 pounds of explosives with a range of 8,800 miles, and further with aerial refueling. To put this into perspective, the famed B-17 in World War II could deliver 4,500 pounds of explosives on an 800-mile mission.

Beginning in October 1964, Hank learned to fly the B-52 at Castle Air Force Base near Merced, California. He did well at training, and particularly excelled at the difficult task of aerial refueling, which is amazing considering how he qualified. He was paired with a major who was having difficulty learning the maneuver, so the major did seven practice runs leading up to his refueling qualification check ride. This meant that Hank did not get to practice the maneuver at all—he could only watch the major and learn from his mistakes. This must have worked well because when Hank took the controls to earn his refueling qualification, he passed it on the first attempt and received a grade of Highly Qualified.

After completing his B-52 training, Hank reported to his first assignment with the 864th Bomb Squadron, 494th Bomb Wing, at Sheppard Air Force Base, just north of Wichita Falls, Texas. Now a First Lieutenant, Hank flew as co-pilot on B-52s flying strategic deterrence missions, which meant they carried nuclear weapons and had to be ready at a moment’s notice to fly missions against the Soviet Union in the event of a nuclear attack. In October 1965, Hank began to fly “Chrome Dome” missions, where his and another nuclear bomb equipped B-52 would fly to the North Pole and remain on station in case a “Red Dot” message came in directing them to attack the Soviet Union. These missions, which were in the winter and thus continually in the dark at the North Pole, lasted a grueling twenty-two hours and involved multiple in-flight refuelings.

In March of 1966, Hank shifted to the 393rd Bomb Squadron, 509th Bomb Wing, at Pease Air Force Base in New Hampshire. Then, in February of 1967, his plane and crew were sent to Anderson Air Force Base in Guam to fly combat missions in the Vietnam War. The missions were twelve hours long, required in-flight refueling, and showed little results as the planes were essentially bombing the jungle from 30,000 feet. After flying two months of these combat missions, Hank’s crew returned to Pease Air Force Base to resume their nuclear deterrent mission.

In May of 1968, Hank’s plane and crew were again sent to Southeast Asia, this time flying out of U Tapao, Thailand, and Kadena Air Base on Okinawa, Japan. The advantage of flying missions out of these locations was in-flight refueling wasn’t necessary as the trips were much shorter—four hours from U Tapao and eight from Kadena—although B-52s flying from Kadena refueled anyway. Hank flew his first mission over North Vietnam on May 8, 1968, and less than one year later completed his 100th combat mission after returning to U Tapao. The crew celebrated with breakfast, champagne, lunch, beer, some sleep, and a mission the next day.

While every mission in a combat zone carries significant risk, certain missions stand out in Hank’s memory. One involved a hydraulic failure, making it unclear whether the left front landing gear could be relied upon when the giant plane touched down. Other flights involved “hung” bombs that failed to drop, so they would have to be carried back to base with the hope that they wouldn’t arm or detonate at the wrong time. On one such occasion, three 500-pound bombs were hung up in the bomb bay. Sometime after the bomb bay doors closed, the three bombs released and fell onto the closed doors. After landing, Hank and his crew quickly evacuated the plane so the ordnance crew could take care of them. On another flight, the crew detected unexpected enemy anti-aircraft fire at 40,000 feet, but fortunately they weren’t hit. Other crews weren’t so lucky, with planes suffering catastrophic structural failures and the loss of everyone on board. Hank and his friends described their missions as hours of boredom interrupted by moments of stark terror.

After five years as a co-pilot and having to re-acquaint more senior pilots from the Pentagon with the B-52’s flight controls, Hank decided it was time to return to civilian life. As soon as he made his intentions known, his Wing Commander told him he’d finally been approved to transfer to fly F-4 jet fighters—all he had to do was pull his resignation papers. Since Hank had always wanted to fly fighters, he accepted. When he received his orders, they weren’t for the F-4 as promised, but for the A-37 “Dragonfly”. He didn’t complain, though, because this was his chance to get into the cockpit and fly something more fun than the B-52. Nonetheless, his record in the B-52 was impressive. He’d flown 172 combat missions over the course of three tours in Southeast Asia, amassing over 3,000 B-52 flight hours, 1,300 of which were during combat missions.

Unlike the B-52 which flew missions at 30,000 feet, or 40,000 feet when over North Vietnam, the A-37 flew attack missions at 1,500 to 2,500 feet in direct support of U.S. ground forces. The aircraft could carry high-explosive bombs, cluster munitions, rockets, napalm, and bullets. It could attack enemy units closer to friendly forces and with much greater accuracy than faster flying fighters, and because its ordnance delivery speed was in the 300 miles per hour range, it could turn and maneuver with precision. As a result, A-37 services were much in demand.

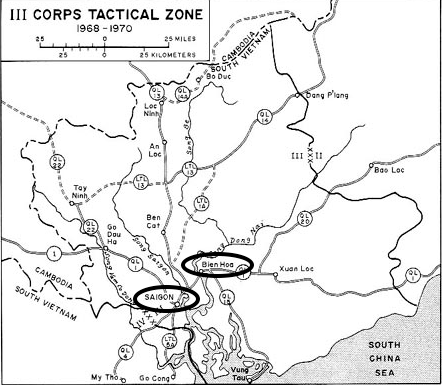

The demand likely accounted for Hank’s quick training pipeline and return to Vietnam. After training stops at Myrtle Beach Air Force Base in South Carolina and England Air Force Base in Louisiana, Hank was back in Vietnam by the end of May 1970. He was assigned to the 604th Special Operating Squadron (SOS), which later became the 8th SOS, at Bien Hoa Air Base, located about sixteen miles from Saigon. In the first nine days after arriving, he flew seven combat missions, which was actually a light schedule since he would later fly up to three combat missions in a day. Quarters were scarce, so he was initially given the room of a lieutenant who was recuperating in Hawaii after being hit by ground fire during a flight. The lieutenant’s bloody parachute harness with a bullet hole in it hung on the door—a stark reminder of the deadly serious business Hank was getting into. Thumps at night outside the “hootches” from mortars fired by the Viet Cong reinforced the point.

Hank flew close air support missions nearly every day. On September 22, 1970, one such mission nearly cost him his life. He was rolling in from 12,000 feet to bomb some boats on the Mekong River when the forward air controller asked if he could strafe the boats with machine gun fire and drop napalm and cluster munitions on a subsequent run. Hank had never done that before but wasn’t aware of any prohibition, so he started throwing switches and getting his guns ready. Coming in low and with his sights on the lead boat, he pulled the trigger only to find he’d forgotten the Master Arm switch. Instead of pulling out of the attack as he should have, he armed the guns and fired directly into the last boat. Thrilled he’d scored a direct hit, he pulled back on the stick and gave the engines full throttle to pull out of his dive. The A-37’s nose came up, but the plane kept heading down toward the water—he hadn’t factored in the extra weight of the ordnance he normally would have expended before doing a strafing attack. His wing nearly hit the mast of the boat he’d attacked and just when his plane was ready to hit the water, the ground effect kept it from bottoming out and he was able to climb back to altitude and resume his attacks. In explaining how he managed to cheat death, he simply says sometimes it’s better to be lucky than good.

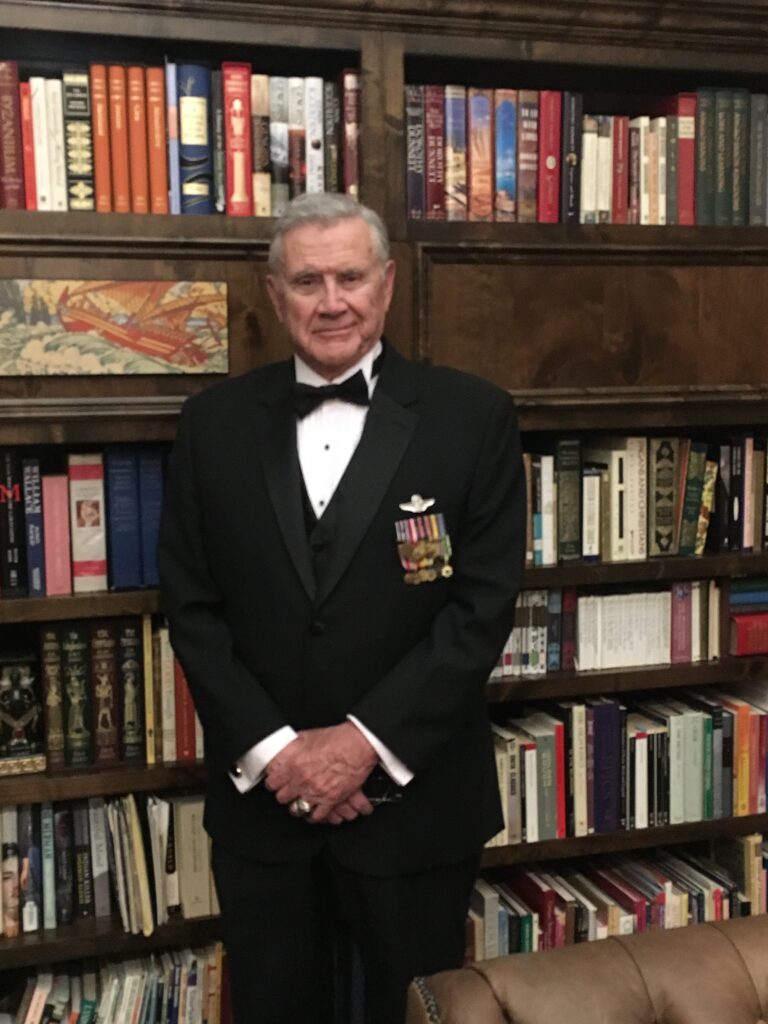

Hank would go on to fly a total of 205 combat missions in the A-37, becoming so accurate with his weapons that he’d put bombs in the mouth of a Viet Cong cave and through the windshield of an enemy truck hiding under a tree. He flew night missions and missions into Cambodia and, when combined with his B-52 tours, amassed a total of 1,605 combat flying hours and earned 2 Distinguished Flying Crosses, 19 Air Medals, and 8 stars on his Vietnam Service Medal. After flying his final combat mission on February 17, 1971, it was time to go home.

Toward the end of February 1971, Hank returned to the United States. After completing graduate school at the University of Arizona and earning a degree in Industrial Engineering, he went to Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Over the next eleven years, he flew every type of airplane, including fighters, bombers, transports, tankers, trainers, and even gliders. Milestones during these years included launching the first two cruise missiles from a B-52 in 1979 and conducting in-flight refueling testing on the new C-141B “Starlifter” transport. He was qualified on four different aircraft: B-52s, C-141s, F-4s and KC-135s, something most pilots never get the chance to achieve. These years tested Hank’s flying skills in other ways, too, like when he had to do an emergency landing of a fuel-heavy B-52 with a severe fuel leak in its left wing. He repeated the heavy landing one month later when the same B-52 suffered an engine failure at the plane’s maximum weight of 488,000 pounds. Hank also served as an instructor pilot, passing along what he learned over the years to less experienced pilots.

When Hank reached eighteen years on active duty, he left the active Air Force and worked as a civilian KC-10 test pilot and later as a pilot for American Airlines. On one American Airlines flight from New York to Miami, former president Richard Nixon was a passenger in first class. Hank went back to meet him and get his autograph, mentioning he had worked for the president in Vietnam. President Nixon told him “the war ended poorly, but we needed to be there.” He then took Hank’s address and later sent him an autographed copy of his book, No More Vietnams. Hank retired from American Airlines in 2001. Throughout his time with American Airlines, Hank continued to fly in the Air Force Reserves, retiring as a full colonel. When it was all said and done, Hank had flown over 10,000 hours in the military and another 8,000 in the private sector, for an incredible total of over 18,000 flight hours.

Now fully retired, Hank lives with his wife, Nancy, in Colorado. He still finds time for volunteer work, as well as speaking to cadets at the nearby Air Force Academy. His advice is simple: life is short so enjoy the ride and leave things better than you found them. These are words we can all live by.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Colonel Hank Hoffman, U.S. Air Force (Retired), for his years of dedicated service to our country. He did his duty under the most arduous wartime conditions, saving countless American and allied soldiers on the ground by bombing enemy targets and providing precision close air support. He continued to serve unselfishly as a test pilot and flight instructor. Welcome home, Colonel Hoffman, and thank you for all you have done for our country.

If you enjoyed Hank’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

July 10, 2020 @ 7:33 PM

Wow ! Hank is really an awesome American and we all should be proud of him! My late dad a Sargent in the army would have loved to meet him. I wonder if I can get a tour in Colorado Springs where he is enjoying his past career

July 11, 2020 @ 9:43 AM

Thanks for your father’s service in the Army, Paul. The Air Force Academy does public tours. You can find out more at https://www.usafa.edu/visitors/.