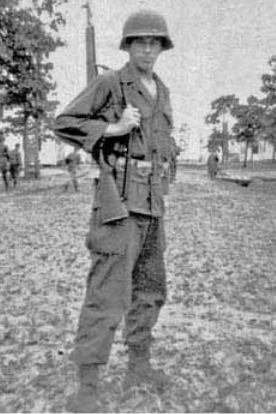

PFC Robert F. Burgess, U.S. Army – From the Italian Alps to Meeting Ernest Hemingway

I find it amazing how one small event can change the entire course of a life. For Private First Class Robert F. Burgess, U.S. Army, that moment came in 1946 when his grandmother told him to check with the Grand Rapids draft board before heading to California with his friends. One year later, instead of sailing the high seas in faraway places, Bob found himself in the Italian Alps dealing with German prisoners of war, spying on Tito’s army, and guarding an ammunition dump nine miles long and four miles wide. The life he envisioned for himself was changed forever. This is his story.

Bob Burgess was born in 1927 and grew up in Grand Rapids, Michigan, during the Great Depression. Despite what one might think, he and his buddies didn’t understand what it meant to be poor because that was all they knew. They played outdoors as long as they were allowed and made their own toys of scrap wood. Bob even earned ten cents a week doing his chores. That magnificent amount of money in those days bought him a hamburger or took him to the Saturday matinee at the local theater.

Bob had a surprisingly normal childhood and quickly learned to sail at his grandparents’ cottage on Spring Lake. As a teenager who liked to read about deep-sea divers diving for treasure, he was anxious to get underwater and see things for himself. Ten years before Jacques Cousteau liberated America’s would-be divers with his self-contained Aqua-Lung, Bob found his own way into the underwater world. At Spring Lake in 1944, he built a diving rig out of a gasoline air compressor, fifty feet of gas station air hose and his father’s World War II Air Warden’s gasmask to dive to a shipwreck in thirty feet of water. He found the ship’s mast festooned with angler’s fishing lures lost over the years. Those lures and old iron parts of the burned wreck were proudly salvaged as his first treasure. He also came up with a cut knee from a corroded deck spike and bleeding from his ears because he knew nothing about what air pressure could do to divers’ ears if they didn’t know how to prevent it underwater.

Bob’s mother and father were both gifted musicians, a talent they hoped to pass on to Bob by having him take clarinet lessons. He soon became quite good. Although he was only twelve years old attending Lexington Grade School, when the high school band director heard him play a solo, he arranged for Bob to get out of Lexington early several times a week to play with the Union High School marching band. In high school, Bob played first chair clarinet in both the band and the orchestra. He graduated in 1945, just as the war in Europe was ending and World War II was drawing to a close.

After high school, Bob had his heart set on doing medical research. He entered Grand Rapids Junior College and took pre-med classes. To earn money over the summer, he worked as the head dishwasher on the Milwaukee Clipper, a passenger and car ferry that ran continually across Lake Michigan between Muskegon, Michigan, and Milwaukee, Wisconsin. When the season came to an end on Labor Day, he and some of the other members of the crew planned to head to California and hire on as crewmembers with the Matson Lines, passenger ships cruising to Hawaii and the far reaches of the South Pacific. But first Bob had to go back to Grand Rapids to pick up some clothes.

Bob lived with his grandmother at the time and when he told her his plans, she said he better check with the Grand Rapids draft board to make sure he was cleared to go. Bob did as she suggested, but the draft board told him he should not go because he was certain to be called up in the next draft.

Rather than being drafted into a service without any choice, Bob and a friend decided to take matters into their own hands and enlist in the regular Army. Given his love of the water, he really wanted to enlist in the Navy, but the Navy required a four-year contract, while the Army only required eighteen months. Plus, if he joined the regular Army and didn’t wait for the draft, he could choose what he wanted to do. So, in October 1946, he and his buddy joined the regular Army. Bob asked to be trained as a medic, thinking he might be stationed in a large hospital where he could get some good medical experience.

The Army sent Bob to Camp Polk (later Fort Polk), Louisiana, for his basic training. Much to his chagrin, the next draft never came. He “was in the Army now and not behind the plow” as the lyrics of a popular song in those days went. Still, Bob enjoyed the military training he received. Since his family members were devoted hunters and fishermen, he was no stranger to handling weapons. On the rifle range he quickly qualified as an expert on the M1 Garand rifle.

Bob’s memories of Camp Polk are of long-needle pine swamps and lots of Louisiana mud, with a few coral snakes tossed in for good measure. The town near the camp where soldiers went on liberty had little to offer other than bars, liquor stores, and prostitutes, so when Bob and his buddy got a weekend pass, they bused to Shreveport hoping to meet a couple of nice girls. His buddy said they would find them in church so that’s where they went on Sunday. The pastor was so pleased to see the two uniformed fellows that he embarrassed them by asking them to stand and introduce themselves to the congregation. A kind family invited them home for a scrumptious dinner and introduced them to their two daughters. Then it was back to marching in the mud and other fun things that most soldiers never forget.

As his basic training was winding down, Bob learned his outfit was to be shipped overseas to Italy where they would be working in medical dispensaries handing out Pro Kits and information soldiers needed for coping with sexually transmitted diseases. Since that didn’t sound as though it would further Bob’s medical career, he checked to see what other options were open. Only two turned up: paratroopers and ski-troopers. Since Bob had skied all his life, the ski troopers sounded like his best bet.

The Army granted Bob’s request and he was assigned to Charlie Company, First Battalion, 351st Infantry Regiment of the 88th Blue Devil Division ski troops. Bob sailed in a Liberty ship from Camp Kilmer in New Jersey to Leghorn (Livorno) in northern Italy, where the harbor was choked with scuttled ships left over by the departing foe. From Leghorn, he and his cronies were trucked northward into the snow and ice country of the Italian Alps. Their destination was the tiny mountain town of Tarvisio, located near the Italian, Austrian and Yugoslavian border crossing, where winter already had a deep freeze lock on everything.

After brief training in Tarvisio, Bob’s company took over the border outpost checkpoint for people who passed from one country to the other. The outpost consisted mainly of several Quonset huts and a stucco building. Squads from the outpost ran snowshoe patrols along the border watching for illegal crossings of potential war criminals. Beside the border outpost was Mount Kapa, where the Americans had a tent outpost on its summit. A horse-drawn sledge carried supplies up the mountain to the outpost, where the men’s duties consisted mainly of crawling out on a snow ledge with binoculars to spy on the Yugoslavian troops billeted across the border. They also reported on the direction of aircraft flying from the Yugoslavian position.

Many of the mountains were honeycombed with gun emplacements and living quarters for the German troops that had been billeted there. Exploring one of them, Bob found a huge barracks room hewn out of solid rock and filled with metal bunk beds and discarded German helmets. Bob’s company even had a contingent of prisoners of war that worked for them and they all became friends with each other.

Charlie Company’s next assignment after outpost duty was to prepare for becoming a spit and polish contingent of the Trieste United States Troops (“TRUST”) garrison. Bob had no way of knowing it beforehand, but Northern Italy had become a major front in the Cold War between Western democracies and Eastern communism. The focal point was the city of Trieste on the Adriatic Sea, located in the northeast corner of the Italian “boot”, sitting in between occupied Italy and communist Yugoslavia. Peace was maintained by dividing Trieste into two zones, one administered by Yugoslavian forces led by Marshal Josip Broz Tito and the other administered by British and American forces. Bob and Charlie Company became part of the newly formed TRUST garrison of 5,000 U.S. soldiers.

Bob’s TRUST assignment began with training on Lido Island near Venice during the early part of 1948. After approximately one month, Bob’s unit trucked to Trieste, arriving in the middle of the night with the sky completely lit up by blue searchlights. They were not looking for aircraft. Instead, they were illuminating a heavily guarded ammunition dump that was nine miles long and four miles wide on nearby Mount Opicina. Yugoslavia strongly desired the munitions.

Bob’s unit billeted in a large stone barracks on Opicina. Apparently, it was once occupied by German soldiers because Bob found several German medals when policing the courtyard area. He guessed they had been thrown away when the enemy abandoned the area before Allied troops arrived. For a week, Charlie Company took turns with other companies guarding the massive amount of explosives collected and stored there from other parts of Italy after Allied combat troops went home. Such things as plastique (a malleable explosive) were stacked in open-ended Quonset huts. Guards did not walk their posts because they were told to shoot anything they saw move. The other order was to never use their helmet’s chinstrap because nighttime intruders had broken necks by jerking a guard’s helmet back. A high barbed wire fence surrounded the dump and at night, Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) squads outside the wire stood ready for someone or something to trip their flares. Whenever a flare went off, the BARs sprayed the area with bullets. Wild animals were often to blame.

After political tensions surrounding Trieste eased, Bob’s experience in Italy became more enjoyable. He was even able to transfer to the Army band located across the parade ground of the caserma when they learned he could play the clarinet. The warrant officer in charge arranged for Bob’s transfer and Bob played with the band for the remainder of his time in Trieste. Eventually, the band was billeted in a small hotel overlooking the Adriatic Sea and life was good. As a result, Bob’s Army tour ended on a high note, with plenty of good food, lots of time to explore the area, and even a beautiful new girlfriend named Carmen. She spoke no English, but Bob was eager to learn Italian.

Bob returned to the United States on a troop ship in 1948, landing in New York City. He had to travel across the country to Fort Lawton, Washington, to finish out his Army service. He was finally discharged after he completed his eighteen-month enlistment, and rendezvoused with Bob Hjellum, an Army buddy from his assignment in Trieste. After planning what they hoped would be the adventure of a lifetime, they caught a passenger ship to Italy and made their way back to Trieste as civilians. The military police in Trieste often stopped them for being out of uniform. None of them believed Bob and his buddy had actually returned to Trieste on their own.

Using benefits they earned as veterans under the GI Bill, Bob and his friend enrolled in a language school in Trieste and spent the summer studying French. Following the Berlitz method, French was all they heard. They associated words with pictures. “Cette couleur est rouge,” and the teacher pointed to red in the Berlitz book. They soon understood the meaning of the words and that was the beginning. They also shared a one-room apartment and lived off the seventy-five dollar subsistence allowance they received each month from the GI Bill.

In October, the two men moved to Neuchatel, Switzerland, to continue their studies in French at the University of Neuchatel. They shared a rooming house with other foreign students who spoke only French. Before long, they were not only fluent in the language, but they also began thinking in French. Despite barely having enough money to live off of, they managed to travel to Paris and other cities, and even made it back to Trieste. When Bob’s friend married the woman he’d been dating in Trieste, Bob headed off on his own.

That spring, Bob and a fighter pilot buddy named Fred Klaus were heading to North Africa when halfway down the boot of Italy they decided to visit the Isle of Capri. Everyone was so happy peacetime had arrived that Capri was still celebrating the end of the war. Bob and Fred rented a villa beside the sea for a dollar a day—the rent was so cheap because of the steep path down the face of a cliff that visitors had to use to reach it. They stayed in Capri for the next three and a half months. After a wonderful summer on Capri, they returned to Switzerland to finish their studies at the university. Then, after living for a time in Paris, Bob returned to the United States in 1950 to study journalism at Michigan State University.

After Michigan State, Bob set off to start his writing career with an Atlanta advertising firm. When that opportunity evaporated before he could even start work, he took a job on a U.S. Government Engineer survey crew to pay the bills, but in the evening he started writing freelance articles at home. After his writing began to take off, he left his job on the survey crew for a stint as an editor for Florida Outdoors magazine, but soon returned to freelance writing. Now writing full time and with money starting to come in, he married the woman he’d been dating ever since joining the survey crew, Julie Ann Scarborough, in June of 1956.

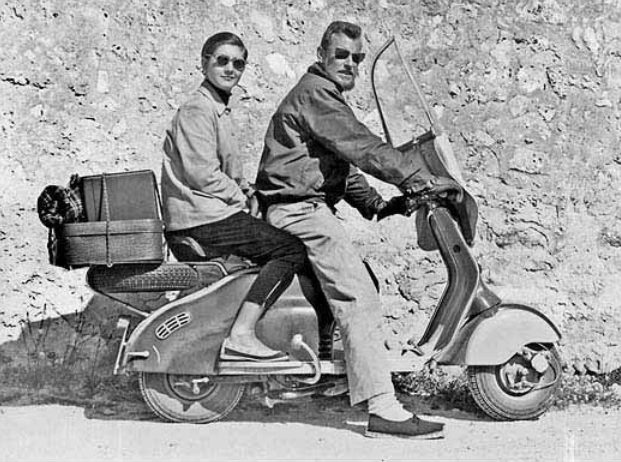

Bob’s marriage to Julie started yet another European adventure. Bob wanted to show Julie what he learned to love about Europe, so in September 1956, they sailed on a passenger liner from New York to France. From there they traveled to Neuchatel, Switzerland, in time for the wine festival and to meet up with Bob’s old friends. As the winter snows arrived in Switzerland, Bob and Julie took a train south to sunny Italy. Wanting a new adventure to write about, they bought a Lambretta motor scooter in Milano, Italy, shipped their heavy baggage to Spain, and started across the Riviera. No one took them for Americans because American tourists never traveled that way.

Five hundred miles later, chasing the sun, they reached Spain and caught a ferry for the Balearic Islands, halfway to Africa. This was dictator Francisco Franco’s Spain and for Americans abroad, it was incredibly inexpensive which, of course, was one of the reasons Bob and Julie were there. For thirty dollars a month they rented a villa overlooking the Island of Majorca’s popular swimming beach. Other American friends moved into the area and enjoyed life where the local Champagne was fifty cents a bottle and life was good. And, since the islanders’ language was a mixture of Italian, French and Spanish, they managed to communicate easily.

The following spring, Bob and Julie took a ferry to Valencia and motor-scootered northward to Madrid where they again enjoyed the lovely exchange rate that enabled them to have a nice downtown apartment for the equivalent of thirty dollars a month. Bob was writing for local magazines in Spain and England while sending home travel articles to American magazines. Julie got a secretarial job at the U.S. Torrejon Air Base in Madrid and the couple spent the next three-and-a half years living and traveling through Spain and other countries in Europe.

While in Madrid, Bob met an American in the Air Force who wanted to go to North Africa to find a fortified mountain in Tunisia where his brother had fought a major battle. On April 1, 1959, Julie and the other man’s wife drove Bob and his friend to the outskirts of Madrid with their backpacks and they hitchhiked and boated to Majorca, then to Marseille, then to North Africa on a ship with the French Foreign Legion. Finally, they found and climbed Hill 609 and returned to Madrid a month later. The trip cost each of them $100 and Bob’s story appeared in magazines and books he wrote. When they were in Tunisia, people seeing them in their rough army clothes and beards waved and called “Castro!” because they looked like Fidel Castro’s ragtag bearded Cuban soldiers. No one ever guessed they were Americans.

Back in Madrid, a Dutch photographer friend of Bob’s told him, “You just missed seeing Ernest Hemingway. He was on his way to Pamplona.” Bob seized the opportunity and proposed to his editor that he cover Pamplona and Hemingway for one of his magazine stories. Bob’s editor told him to go get it, so Bob grabbed his camera, a sandwich, and his leather bota of wine and motor-scootered into the Guadarrama Mountains 250 miles away. The next morning, he was in Pamplona and the fiesta was in full swing. He saw Hemingway surrounded by people and Bob knew he could not get close to him. So, he continued to photograph the running of the bulls for his magazine story.

The next day, Bob was going into the bullring and was looking at his ticket to see where he had to go when he realized Hemingway was right beside him doing the same thing. They spoke together. Bob mentioned that during his recent trip to North Africa, no one thought they were Americans. Hemingway wanted to hear about Bob’s adventure, so after the bullfight Hemingway came striding up through the stands to talk with Bob. It ended with Hemingway inviting him to come meet the rest of his mob, so for the next two days they drank together while Bob snapped photographs and later wrote about it for his book, Hemingway’s Pamplona, Then and Now.

Bob continued his amazing life after he and Julie returned from their European travels. They settled in Chattahoochee, Florida, where Bob wrote freelance articles for sporting magazines, dove on shipwrecks off the coast, and wrote novels. For the next twenty years, he also wrote sport fishing and diving stories for Florida Sportsman Magazine. Even today, well into what others would call retirement, Bob remains a prolific writer, writing books about snipers and other soldiers in the Vietnam War that have won him praise from the family members of those who served. In fact, in writing Bob’s story, I consulted his book Sailing to Adventure, The Time of Our Lives, and found his life story so fascinating, I just couldn’t stop reading! I encourage you to read Sailing to Adventure, The Time of Our Lives so you can experience Bob’s extraordinary life through his own words. You can find Sailing to Adventure, The Time of Our Lives and all Bob’s many books on his author page on Amazon.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Private First Class Robert F. Burgess, U.S. Army. His distinguished service in northern Italy and as part of the TRUST garrison helped ensure freedom for the people of Trieste and bring stability to the region in the aftermath of World War II. Even today, Bob continues to serve military families by writing about the deeds of U.S. servicemembers. We truly wish Bob fair winds and following seas.

Note: Photographs included in this story were used with the permission of Bob Burgess. Bob also kindly collaborated in writing portions of the story.

If you enjoyed Bob’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.