SGT Daniel J. Smith, U.S. Army – From Army Medic to Coaching Wounded Warriors

Successful people have one thing in common—they turn life’s challenges into opportunities. Sergeant Daniel Smith, U.S. Army, had lots of challenges early on but overcame them all. His path to success began with a tour of duty as an Army medic, led to his coaching Wounded Warriors in international competitions, and continues to this day through his participation in triathlon and swimming competitions and coaching high school students and para athletes. This is his story.

Daniel grew up on a farm in Firelands, Ohio, not far from Vermilion, which is located on Lake Erie between Cleveland and Toledo. He had a tough time with math and English in high school, not knowing at the time he was mildly dyslexic, making classwork difficult. He also had a tough time finding a place to fit in at his high school with all the cliques, so by the time he graduated in June of 1986, he was ready for a change.

The problem was Daniel saw his options as limited. He didn’t have the grades for college. He also didn’t want to work at the local Ford plant or Goodrich chemical plant because he wanted more potential for growth. His one ticket out was the Army, but there was a major drawback to that, too. He didn’t want to have to use a gun to kill—he wanted to help people instead.

Rather than give up on his dream, Daniel called the Army recruiter who had visited his high school. The recruiter had him take the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) and he scored so high he was able to choose whatever he wanted to do. He opted for field medic, which was a perfect fit. His sole purpose in the Army would be helping people and it would allow him to get a fresh start in a new place. It would also earn him benefits under the GI Bill and the opportunity to attend college after he served. He signed his enlistment papers and agreed to give the Army the next three years of his life.

Daniel reported for duty to the Military Entrance Processing Station (MEPS) in Cleveland in the fall of 1986. After passing his physical and being sworn in, he was put on an airplane and sent to Fort Bliss, Texas, which was quite a change for him as he’d never ventured far out of Ohio before. He and a busload of recruits arrived sometime after midnight and were told to file off the bus, where they stood in the cold night air and snow flurries. After being berated outside for forty-five minutes, the recruits flowed through two lines to get their hair roughly shaved and their uniforms issued. Daniel remembers trying to get to sleep in the barracks that night in an uncomfortable bed with the sound of other young men crying themselves to sleep. As someone with a strong personality who did not like to conform to authority, he thought his life was over—and this was just the first night.

The next day began with physical training and lots more yelling. Daniel couldn’t understand why the instructors had to act so mean. He remembers being singled out because, although he was an excellent athlete in high school, he did the fewest pushups in his company. Getting mocked really angered him, so he set out to prove the First Sergeant wrong. By the end of Basic Training, Daniel could do more pushups than anyone else in his company and was the most improved on the run and in sit-ups. Given his excellent performance overall, he earned the Soldier of the Cycle award.

After Basic Training, Daniel reported to Advanced Individual Training (AIT) for medics at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. His job as a medic would be to keep wounded soldiers alive until they could be transported out of the area of immediate combat and be treated by a doctor. This meant he had to learn how to give IVs, do tracheotomies, stitch up wounds, and remove partially amputated limbs. His training lasted four months and he graduated second in his class of 800 people.

Now a Specialist (E-4), Daniel reported to his first assignment, the 42nd Field Hospital in Fort Knox, Kentucky, during the late spring of 1987. Upon arrival, Daniel began training with his unit on how to quickly deploy and set up a 200-bed hospital. As the Army’s only deployable field hospital, the entire hospital could be packed and loaded onto transport aircraft, dropped into a landing zone, and reassembled in short order. However, since this was peacetime, the medics in the unit had to engage in other activities to keep their skills sharp. One of Daniel’s favorite training rotations involved working at the Ireland Army Community Hospital, where he worked in surgery, the Intensive Care Unit, and the Emergency Room. He found the toughest part of the hospital assignment was dealing with grief counseling.

Not all Daniel’s training was medically related. In 1988, Kentucky was besieged by forest fires. Daniel’s First Sergeant asked his team whether anyone in the unit could drive a big truck. Having driven some stick shift farm equipment growing up in Ohio, Daniel volunteered. He soon found himself with a buddy driving a two-and-a-half-ton water truck through the mountains of Kentucky into the fire zone to help fight the fires. When the firefighters used up all the water, Daniel would make another trip for more. He and his buddy often pitched in to help fight the fires in an effort to give some of the exhausted men on the front line a break.

At one point, Daniel and his buddy dozed off in the truck while they were parked in the fire zone. When they woke up, they found the truck surrounded by fire. Afraid they would be burned to death and that the truck would explode, they used water from the truck to clear a path back down the road to safety. It was a close call.

The other significant training Daniel participated in consisted of two three-month assignments each year with either the 82nd Airborne Division or the 101st Airborne Division at the National Training Complex (NTC) near Death Valley, California. NTC is a giant training area in the Mojave Desert, making it the perfect location for training U.S. forces for desert warfare. Daniel would be assigned as the medic for an airborne infantry unit and exercise with them under the intense temperature extremes of the Mojave Desert. The training was serious business and dangerous, as the following incident illustrates.

During one nighttime exercise, Daniel’s unit was convoying down a mountain in blackout mode, so drivers could only see the vehicle in front of them using night vision gear. Daniel was in the last vehicle in the convoy, which was typical since he was the medic. That way, if anyone had any medical issues, they could get out of their vehicle and wait for Daniel to come by. Daniel’s vehicle, however, was a Vietnam era M561 Gama Goat, which often broke down and was unreliable in the rocky terrain. Capping off the setting, Daniel’s driver was a devout Christian, so he was praying and praising Jesus out loud while he navigated the treacherous road at the rear of the convoy. Suddenly, there was a thud and the Gama Goat came to an abrupt stop—they’d hit a boulder and the vehicle’s front wheel broke off. Without a radio and in the pitch-black darkness, they had no way to alert the other vehicles in the convoy, which continued driving unaware that Daniel’s vehicle had become disabled. Daniel and his driver stayed with their vehicle for three days with no food or water, watching out for scorpions, listening to the howls of a pack of coyotes surrounding them every night, and even scaring off a mountain lion, until a helicopter finally spotted them and they were rescued. Had the helicopter not seen them, Daniel is sure they would have died.

Not everything Daniel did was training. On one occasion, he helped save an ROTC cadet who fell eighty feet into a ravine and onto her M16 rifle, breaking her back. On another occasion, he prevented a soldier from bleeding to death after his hands were crushed during repair work on a tank. In each case, Daniel was awarded an Army Commendation Medal for helping save the soldier’s life.

Daniel was discharged in the late summer of 1989 and returned to Ohio. He began working at a lakeside bar in Vermilion where lots of people from New York and New Jersey vacation. One day, two women at the bar asked him if he wanted to go to the beach with them and he accepted. At the beach, one of the women started setting up camera equipment and asked him if she could take a few pictures. That impromptu photo shoot led to Daniel entering a modeling competition in New York City, which he won in November of 1990. He then began a fourteen-year modeling career that had him doing photo shoots in countries around the world and castings with many top models and photographers.

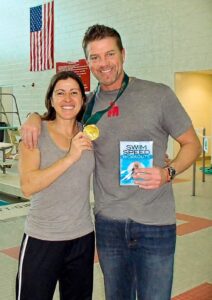

Recognizing he would not be able to model forever, Daniel learned the art of photography from the master photographers doing his shoots and he started his own photography business. He also began working out more intensely and fell in love with biking, swimming, and running, so he was a natural for triathlons. In 2002, after he’d left New York and moved back to Ohio, the athletic and the artistic sides of his life merged into an opportunity to take photographs for an Olympic gold medalist swimmer, Sheila Taormina, who was writing what would turn out to be a worldwide best-selling series, Swim Speed Secrets.

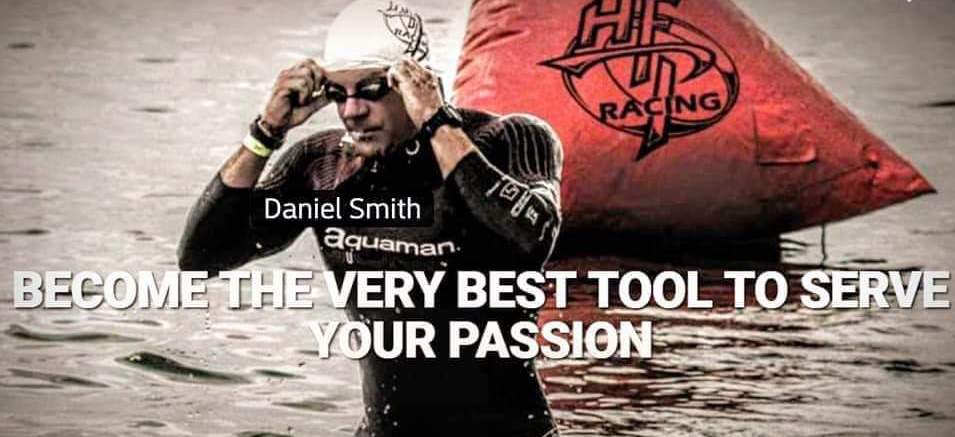

In 2011, when Sheila and Daniel were promoting the Swim Speed Secrets series, they were given the opportunity to do a swim clinic for the U.S. Wounded Warrior Battalion in Colorado Springs. One week later, they were hired to coach swimming for the Marine Wounded Warrior team to prepare them for the international Warrior Games. The United Kingdom’s Prince Harry would subsequently throw his full support behind the games and their name was changed to the Invictus Games. Daniel served as the assistant swim coach for 2011, 2012, and 2013. He worked closely with many Wounded Warrior athletes from the United States and allied countries during those years and considers them to be some of the most rewarding years of his life. He still does swimming and triathlon clinics whenever needed.

Daniel continues to be an avid triathlon participant and, at fifty-two, is a national-caliber master swimmer. More importantly, he coaches both track and field and swimming for Avon Lake High School, located on the outskirts of Cleveland. One student para swimmer he coaches was a silver medalist at the Parapan American Games and is currently training to qualify for the 2021 Paralympics in Tokyo. He also does an occasional modeling shoot, proving he still has it after all these years.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Sergeant Daniel J. Smith, U.S. Army, for his distinguished service in the 42nd Field Hospital and for his dedicated efforts working with Wounded Warriors. We are also thankful that he continues to work with high school athletes, helping them aspire to be the best they can be. We wish him continued success and fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Daniel’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

April 21, 2020 @ 9:39 PM

Thank you Dan for being the amazing coach that you are to my girls. They are very lucky to have you! The world needs more people like you to motivate and inspire them to be their best. You have led an exciting life and I am thankful for you sharing it with our family.

June 22, 2020 @ 9:44 PM

Thank you Kelly..i love coaching them and they inspire me also and you are a terrific mom they are lucky to have you

I can’t wait to see what happens our senior season I know they are only going to get faster ?

coach Daniel

April 22, 2020 @ 7:01 PM

Thank You for your service!

April 26, 2020 @ 7:20 AM

Much appreciation and respect.