Specialist Billy Terrell, U.S. Army – Helping Children Devastated by the Vietnam War

Wars inflict pain and suffering—no one knows that better than Specialist Billy Terrell, U.S. Army. He saw war’s horrors firsthand and even heard a priest reading him his last rights as he lay on the brink of death in a field hospital in Vietnam. Yet Billy and the other members of his unit were able to look past the death and destruction to help South Vietnamese nuns carve out a sanctuary for one hundred children orphaned by the war. Looking back, Billy realizes the sanctuary saved him, too. This is his story.

Billy’s childhood can best be described as riches to rags. He was born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1944, to a solid middle class working family. His father owned a successful construction business, which at its peak employed twenty-two people. With two cars in the driveway and the only television on the street, it looked like Billy’s family was living the American dream. That dream came to an abrupt end in 1952 when the construction company went bust, thrusting Billy’s family into poverty. In the first of many moves over the next ten years, Billy’s father relocated the family to the coast near Asbury Park, New Jersey.

The move did not improve the family’s financial situation. Many nights, Billy and his siblings went to bed cold and hungry, while his troubled mother and despairing father proved unable to support their family. As if admitting defeat, Billy’s father made him quit school when he was sixteen to find a job to help support the family. Dressed in rags and missing his four front teeth after they became brittle, broke, and had to be pulled, Billy found it impossible to find anything but the most menial low-paying jobs. That’s when his Aunt Laura came to his rescue by letting him live with her in Newark and paying for the dental work he needed to replace his missing front teeth. With the newfound confidence of a full smile, Billy set out to find a job and a way to get started in show business.

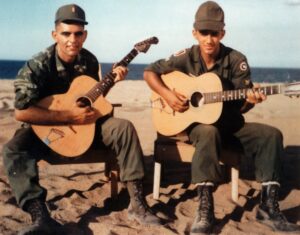

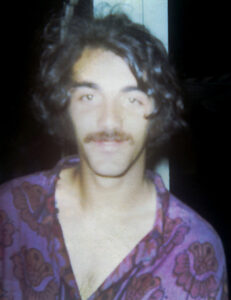

Billy’s first break came when he was seventeen working as a dishwasher at the Howard Johnson’s in Asbury Park. The bell captain from the nearby Empress Motel saw how hard Billy worked and got him a job bussing tables and delivering room service. Although he only had the first Monday of each month off, Billy taught himself to play guitar and started playing gigs around town. Sometimes the acts performing at the Empress Motel would ask Billy to join them on stage to do a song or tell a few jokes. Clay Cole, the host of a popular New York TV show, saw Billy and said he had some people he wanted Billy to meet in New York. One week later, Billy, who now at eighteen had Frankie Avalon looks and an infectious smile, signed with his first manager and did his first “demo” record. Although he didn’t get a recording contract, he inked a deal as a songwriter with Kama-Sutra Productions for $50 per week. By the middle of May 1965, The Duprees had recorded Billy’s first song on Columbia Records, They Said It Couldn’t Be Done. It looked like Billy was finally on his way, but Uncle Sam had other plans.

In May of 1965, Billy received his draft notice and notified his employer that he would soon have to leave for the Army. The people at Kama-Sutra Productions didn’t want him to go, even holding a séance for him in a blacklight lit room with a beatnik talking in tongues and banging on a gong. When the séance didn’t change Billy’s mind, they suggested he report for duty in women’s underwear and holding a dead fish. Having none of it, Billy thanked the staff for their concern, but told them his grandfather had immigrated to the United States in 1902 from Italy and made a life for himself and his family, so he felt it his duty to serve his country in the Army. Billy said goodbye and walked out of Kama-Sutra Productions—his grandfather died the next day.

The Army delayed Billy’s report date so he could attend his grandfather’s funeral, but on August 5, 1965, it was time to go. Billy reported to the Military Entrance Processing Station (MEPS) in Newark. From there he was bussed with his fellow draftees to Fort Dix, New Jersey, for eight weeks of Basic Training. Although it was tough, Basic Training gave Billy a sense of self-worth he had never had before. Now he was part of a team, had a clean uniform to wear and three meals a day to eat. He started to become healthier and gain weight, and developed a sense of pride in what he was doing. At the same time, he recognized what he and all of the other draftees had in common. They were all poor and uneducated, from the bottom rung of society. Despite his new-found pride, he couldn’t help but think society thought them expendable. Billy would wrestle with this dichotomy throughout his time in the Army.

After completing eight weeks of Basic Training and eight more weeks of Advanced Infantry Training (AIT) at Fort Dix, Billy and a friend he made at Basic Training, Bob Reed, reported to Quartermaster School at Fort Lee, Virginia. Quartermasters manage the Army’s logistics and supply chain, making sure the fighting forces have what they need to win battles. Billy and the other soldiers trained for four weeks, making ready for assignments in Vietnam.

Part of the preparations included an orientation to duty in Vietnam, where the instructor told the new soldiers that they could not ship their cars to Vietnam and that their families could not visit them there. This offended Billy because it was obvious they could not do these things—Vietnam was a war zone. Irked that whoever prepared the orientation must have thought that he and the other trainees were ignorant, Billy stood up when the instructor asked if anyone had any questions. He said, “you’ve told us throughout training that in South Vietnam, we can’t tell who the enemy is because the Viet Cong have infiltrated the villages. Why don’t we just go into North Vietnam and get this over with?” The instructor didn’t appreciate Billy’s strategic thinking and sent a sergeant over to tell him to sit down, which he did.

The night before Billy’s Quartermaster class was to ship out, a sergeant and some Military Police roused Billy, his friend Bob Reed, and two others. The sergeant told them to pack their gear as they were moving out now. Not knowing what was going on, the men gathered their gear and went with the sergeant to the train station, where they were put on a train for Fort Riley, Kansas. There they joined the 96th Quartermaster Battalion, which would soon deploy as a unit to Vietnam. By May of 1966, the unit was ready. After transferring to Oakland, the men in the unit boarded the USNS General Nelson M. Walker (T-AP-125), a World War II era transport ship, en route to Vietnam.

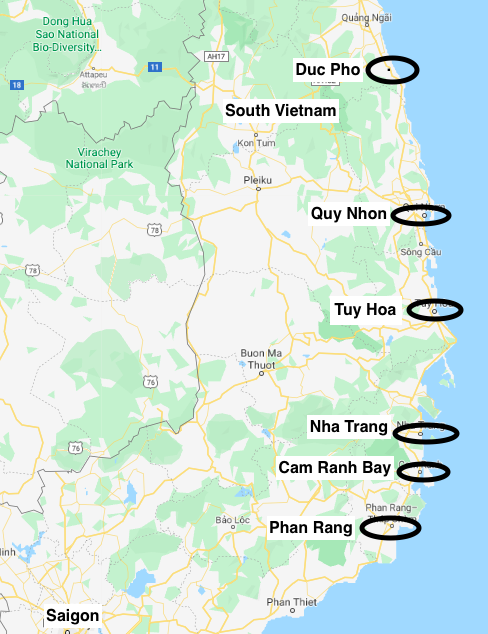

The ship arrived in Cam Ranh Bay, Republic of South Vietnam, on May 28, 1966. Billy was ferried ashore in a Navy LCU (landing craft – utility). He and Bob Reed made it a point to take their first step onto Vietnamese soil together. Once everyone was ashore, the battalion broke into two companies, with Billy being assigned to the 226th Supply and Service Company. The unit spent a few days in Cam Ranh Bay and then drove by truck to Phan Rang, about eighty kilometers northeast of Saigon, where they set up camp. Billy remembers the camp being an isolated jungle setting not far from shore, with waist-high grass all around the camp.

Phan Rang was a staging area for the company, so they had little to do other than prepare for their next assignment. This exacerbated racial tensions, which tended to surface when the men had free time on their hands. The unit included white soldiers from the South and African American soldiers from the North, and they did not get along. The unit also had members who had been given the choice of joining the Army or going to jail after committing violent crimes, so maintaining discipline was difficult. At night it could be particularly scary, with junior officers and sergeants sometimes being attacked and beaten. Billy was able to get along with all groups, because he had life experiences in common with both the enlisted soldiers and the officers, so he was left alone. Still, the racial tensions complicated an already dangerous wartime environment.

At the end of July 1966, Billy and the rest of the 226th Supply and Service Company embarked a Navy vessel and sailed up the coast to Tuy Hoa, which would be their supply base camp for the remainder of Billy’s tour in Vietnam. The first order of business was to set up tents to live and operate out of. Then they laid down a metal landing surface to allow supply aircraft to land and take off from the camp.

Billy was responsible for handling the unit’s mail, so he convinced the Company Commander, Captain Virgil Bon, to allow him to set up a post office in a Conex box. He used tin cans labelled alphabetically to sort letters, which he would then deliver to the men in his unit. He also flew by helicopter to units all around the area to deliver mail, sometimes bringing an added surprise like cans of soda on ice to the men in the field. More than once a cold soda resulted in a hug from a grateful recipient. Despite these lighter moments, the delivery runs were deadly serious. On more than one occasion, Billy remembers hunkering down in the helicopter while the machine gunner blasted away at targets below with the aircraft’s M-60 machine gun.

Billy also stood perimeter guard duty at night, which could be terrifying not only because it was so dark, but also because he was isolated and easy prey for the convicted felons who really didn’t want to be in the Army. Viet Cong infiltrators were also a concern, but primarily because they wanted to interrupt a fuel pipeline running from the beach to the base. One bright moonlit night, Billy heard tapping on the pipe, so he slipped out of the bunker he was manning and took cover in the nearby brush just in case the bunker was being targeted. The enemy did not attack, but it was a terrifying experience, nonetheless.

Life was also made difficult because Billy and the other soldiers could not trust the local population, who were friends by day and Viet Cong sympathizers by night. Vietnamese locals, who often worked at the camp, sometimes planted grenades and other charges among the pallets of supplies. When the forklift operators tried to move the pallets, they were injured or killed. The roads around the camp were also mined, so soldiers were always at risk of stepping or driving on a mine. The lack of trust flowed both ways as some of the more out of control soldiers tormented the locals. On one convoy driving along a narrow dirt road, Billy saw a truck driver intentionally swerve toward an ox pulling a cart carrying a farmer and his family. The animal panicked and bolted, throwing the farmer’s family under the truck, where they were crushed. The anguished cries of the farmer distraught over the death of his wife and children still plague Billy.

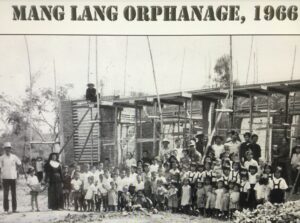

In the midst of all this suffering, a ray of hope cut through the war and brought life to everyone it touched. One afternoon in September 1966 when Lieutenant John Sheer was burning inedible C-rations, they discovered two nuns picking through the cans and scavenging for food. Lieutenant Sheer told the nuns, who spoke no English, that the food was bad and gave them $10 worth of military scrip to buy some food. An hour later they returned with a priest who spoke some English and could explain to Lieutenant Sheer the nuns’ plight.

The priest explained that the nuns ran the Mang Lang Orphanage, which had been destroyed by the Viet Cong. They had escaped with about one hundred children and were now jammed into the tiny wing of a ramshackle hospital near town. Lieutenant Sheer asked Billy to go with him to visit the site. When they saw it, they were immediately convicted to help Sister Michelle and Sister Teresa with the orphanage. They began by setting out cigar boxes around the camp where soldiers could contribute money. Lieutenant Sheer also asked his church in Chicago to donate. Within a few weeks they had collected $600, which was enough for the nuns to buy land and build a new orphanage.

That wasn’t all the men did. Lieutenant Sheer, Billy, and other members of his unit became frequent visitors. Billy took the children chocolate he’d traded other soldiers for in return for the cigarettes he received in his C-rations. He also taught the boys, who were all under ten, to play baseball. Every time Billy visited, the children ran to him and clung to him when he had to go.

The Mang Lang orphanage became a sanctuary for the children, where they actually had enough to eat and people who loved them. Just as important, the orphanage became a sanctuary for Billy and the other soldiers of the 226th Supply and Service Company, offering a lifeline to humanity in the middle of so much death and destruction.

In December 1966, Billy participated in a convoy led by soldiers from the 28th Regiment of the South Korean Army, who provided tenacious security for Billy’s base camp. As the convoy drove through the heavy monsoonal rain, Billy became delirious and ran a high fever. The Korean officer in charge of the convoy ordered that Billy be taken to the 563rd Medevac Company, which had a landing zone for casualty evacuation helicopters (“Dustoff choppers”) on a hill north of Tuy Hoa. The plan was to evacuate Billy to the 67th Evacuation Hospital in Quy Nhon, but the rain was too heavy for chopper operations. With the only tent already full of casualties, Billy and several other evacuees were wrapped in ponchos and left outside in the rain until morning. When the weather cleared, Billy was flown to the 67th Evacuation Hospital, and subsequently transferred to the 8th Field Hospital in Nha Trang, where they had the expertise to treat him.

By the time Billy arrived, he was baking with a 105-degree malaria-induced fever and hallucinating. The doctors said they had to bring his fever down or they would lose him, so they gave him an ice bath, which was incredibly painful. Moreover, when they removed his right boot, they found a hole through his foot between two of his toes and his skin rotting to the point where his shin bone was visible. After the ice bath, Billy remembers being put to bed and overhearing a doctor instruct the nurses to take his temperature every thirty minutes, give him a shot every hour, and if he makes it until morning he might have a chance.

Although his eyes were swollen almost completely shut, Billy could see USO Christmas lights decorating the hospital tent. Evoking strong emotions even now, Billy remembers staring at the Christmas lights and repeating over and over, “Oh my God, what is my mother going to do?” He was afraid that if he closed his eyes and fell asleep, he would die. Eventually he passed out. Later he saw an intense light and thought he must be dead. He jokes now that he started looking around for lost relatives, but seconds later he realized the bright light was the sun peeking through a gap in the sandbags surrounding the tent. He’d made it through the night!

Later in the day, Cardinal Francis Spellman (the Roman Catholic Vicar of the U.S. Armed Forces), the great evangelist Billy Graham, and motion picture star and comedienne Martha Raye, visited Billy. Reflecting that Billy was still in very serious condition, Cardinal Spellman administered him his last rights while Billy Graham held his hand and Martha Raye held his feet. Cardinal Spellman also gave Billy a crucifix, which he took home from the war.

After a day or so, the doctors told Billy he had to start walking to help circulate his blood or he would not make it. He was so weak, though, that he couldn’t even lift the heavy end of a spoon from a tray to feed himself. Then Martha Raye, who the soldiers affectionately called “Colonel Maggie”, reappeared at his bedside. She repeated what the doctors told him and said he wasn’t going to die on her watch. Then she helped Billy stand and told him to put his feet on hers and she walked him across the room. She visited at least one more time and did the same thing, until finally Billy gained enough strength to walk. Billy is certain that if Colonel Maggie had not come by to help him, the malaria would have killed him.

Although reduced to eighty-nine pounds and looking like a living skeleton, Billy began to recover. He wondered whether he would be sent to the Philippines or Japan before going home, but the Army had other plans. His doctor informed him that he was being sent back to his unit. Billy asked how that could be given his weight and that he’d been in the hospital for over thirty days. The doctor countered that Army regulations required he be returned to his unit because he’d not been in the same hospital for over thirty days. Knowing he couldn’t fight the man and reminded of his Basic Training feelings of being expendable, Billy shrugged it off and returned to his unit to finish out his tour.

Nearing the end of his tour, Billy and his friend, Lieutenant Jordan Klempner, flew in a Huey helicopter from Tuy Hoa north to a fire base near Duc Pho, where the helicopter came under fire. The pilot guided the helicopter to a landing zone behind four 105mm howitzers firing rounds at the enemy. Billy and Lieutenant Klempner jumped to the ground before the helicopter peeled away. They ran toward a group of vehicles assembled nearby and boarded a three-quarter ton truck in a convoy heading to Duc Pho. As they passed through several hamlets along the way, Billy sensed something wasn’t right and laid down on the bed of the truck with a round chambered in his rifle. Lieutenant Klempner, who was still standing in the back of the truck, asked Billy what he was doing. Billy said it was too quiet—he couldn’t hear birds anymore—just the sound of the trucks. Lieutenant Klempner got down too and moments later, gunfire erupted at the front of the convoy, killing the lead driver. A firefight ensued, pinning down Billy and Lieutenant Klempner. Eventually, two jets dropping napalm suppressed the attack and the convoy was able to continue to Duc Pho, carrying its dead and wounded. The next day, Billy and Lieutenant Klempner returned to the landing zone in a column of vehicles that included tanks at the beginning and the end, with a Huey helicopter gunship overhead spraying the terrain on both sides of the road with M-60 machine gun fire. After returning to the landing zone, Billy and Lieutenant Klempner flew back to Tuy Hoa. Billy considers the attack on the convoy on the road to Duc Pho to be his most trying experience of the war.

Because Billy only had a few days left in country, Captain Bon sent him to the relative safety of Cam Ranh Bay to await his flight back to the States. When he boarded the chartered Northwest Orient airliner for home, he was surprised to see his friend, Bob Reed, on the flight. Everyone onboard, from the most junior soldier to the most senior officer, sat in silence as the plane took off, all instinctively with their eyes closed and holding hands. When it was clear the plane was out of range of any danger, the men erupted in cheers, hugging, and tears. They had survived their tours in Vietnam. The date was May 29, 1967–they were finally going home.

Once back in the States, Billy faced many challenges. The first came when he went home and learned his father had suffered a serious heart attack while he was gone. Billy initially felt responsible because he believed the news of his near-death experience from malaria had been the cause. The second challenge came from the way everyone treated him. He had grown up watching World War II movies and saw the welcome home the troops received. He expected the same, wearing his uniform around town when he first arrived home. Instead of being welcomed, people rejected him.

Dejected and suffering from the trauma of war, Billy turned to the bottle. Things got so bad that at one point, he traded the crucifix he’d been given in the field hospital in Vietnam for a drink. He reached rock bottom on June 23, 1968, when he showed up drunk and disheveled for his brother’s wedding. Afterwards, he looked at himself in the mirror and felt like a disgrace. He’d survived the war and made it home to his family. Thousands of other soldiers hadn’t been so lucky. Out of respect to them and their mothers, he had to fix himself. He gave up drinking that day and set his sights on getting back into the music industry. That meant finding a cheap office in Asbury Park and buying a broken-down piano for $25, which he taught himself to play by practicing up to twenty hours a day.

Five months later, singer Debbie Taylor took a song Billy wrote, Never Gonna Let Him Know, to #5 on the R&B chart. Billy never looked back. Over the course of his career, he wrote, arranged, and/or produced over 2,000 records, with 64 hitting national and international charts. He produced records for the likes of Bobby Rydell, Helen Reddy and Maria Muldaur, and helped rekindle the career of his teen idol, Frankie Avalon, in the 1970s by creating a disco arrangement of Frankie’s 1959 #1 hit song, Venus. The 1976 hit helped Frankie land the role of Teen Angel in the blockbuster movie, Grease.

Despite all his post-war success, Billy still had a few more scores to settle. He’d moved forward with his life after his brother’s wedding by trying to suppress his memories of the war, only to have them continue to torment him. Agent Orange also took its toll, afflicting him with several forms of cancer, all of which he’s beaten. His ultimate success came when he realized he continued to suffer from PTSD and sought counseling with other veterans to address it.

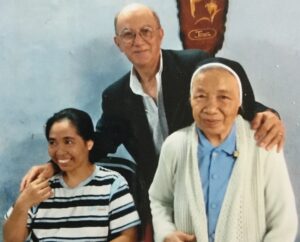

In 2008, Billy found a trove of photographs of the Mang Lang orphanage he’d taken during the war. Curious, he searched the Internet and discovered the orphanage was still there, as was Sister Michelle. Then he did something he thought he would never do—he returned to Vietnam to visit the orphanage and confront some of his demons.

Billy’s visit to the orphanage in 2013 was life-changing, once again providing him with a sense of peace and sanctuary. He met with Sister Michelle, now in her eighties, and four women who remembered Billy from his visits when they were children during the war. One of the women, Ahn Doe, who had deformed feet, had been dropped off at the orphanage by her family because they didn’t want to raise a disabled child. During Billy’s 2013 visit, she told him through an interpreter that she loved the sweets Billy used to bring during his visits to the orphanage and that when Billy held her, it was the only time she ever felt safe. Ahn’s revelation brought Billy to tears, as he realized his efforts had made a difference. It was the beginning of the healing process.

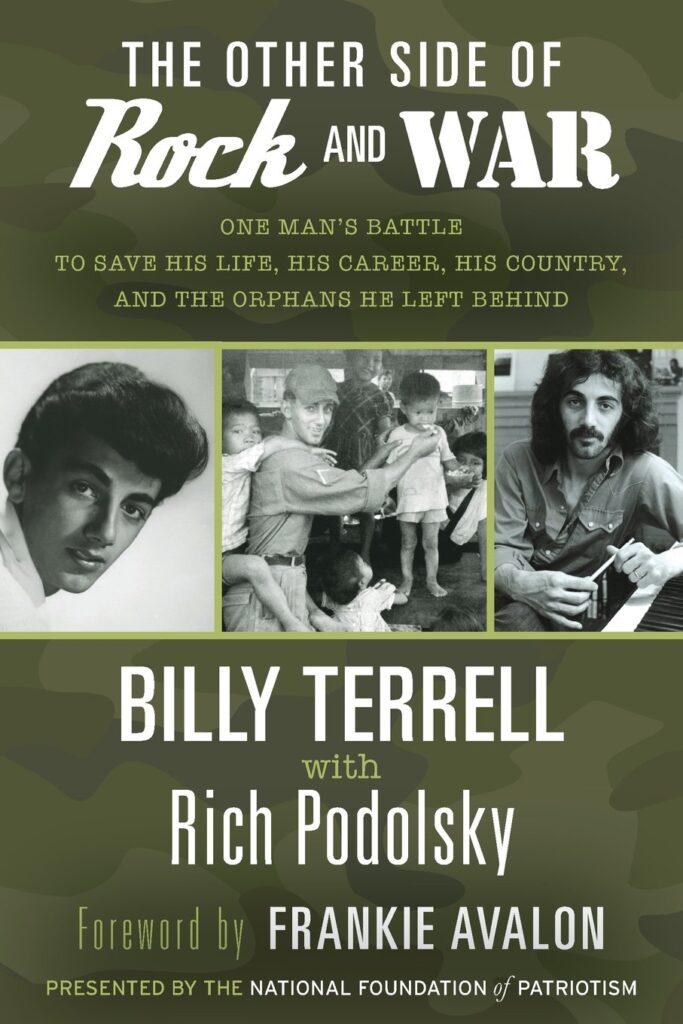

Now semi-retired, Billy freely shares his story with civic groups, veterans organizations, and schools. He’s even written his memoir, The Other Side of Rock and War, published by the National Foundation of Patriotism in 2018. If you’d like to learn more about Billy’s amazing life, including stories about the rock and roll legends he’s encountered like Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, George Harrison, Ravi Shankar, Cream, and Janis Joplin, I encourage you to read his book, which is available through Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Specialist Billy Terrell, U.S. Army, for his dedicated service to our country during the Vietnam War. Not only did he do all the Army asked of him and more, but he also epitomized the honor and dignity of the American soldier through his kindness to Vietnamese orphans whose lives had been upended by the war. Billy gave the most vulnerable victims of the war hope and made them feel safe, changing their lives forever. He continued to change lives after returning home by bringing smiles to people’s faces through his music. For all he has done throughout his life, we thank Billy and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Billy’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.