Specialist 4 Tom Garvey, U.S. Army Lesson from Vietnam: Glad to be Alive

Think of your most stressful day on the job—looming deadlines, unhappy bosses, sales quotas, late nights, and people who can’t get along. Then consider what Specialist 4 Tom Garvey went through every day during his tour in Vietnam from 1967-1968—fire missions with high explosives, incoming mortar fire, rocket and artillery attacks, and the constant possibility of his unit being overrun. Listening to Tom’s story helped me view my life’s experiences from a different perspective. I hope his story will have the same effect on you.

When Tom graduated from Franklin K. Lane High School in Brooklyn, New York, in 1965, his immediate thought was to get a job and earn some money. He also wanted to go to college, but coming from a poor family, the only way he could continue his education was to work during the day and go to school at night. Tom’s mother suggested he apply at the New York Stock Exchange, which he did, and he landed a job as a page taking stock purchase and sale orders from the brokers on the floor to the specialty brokers for execution. He also enrolled at Brooklyn College, taking night classes in pursuit of a bachelor’s degree in economics.

Things were falling in place for Tom until he was drafted in 1966 at the age of 19. On October 19, 1966, he was sworn in at Fort Hamilton at the foot of the Verrazano Bridge in Brooklyn. As he stood in line after taking the oath, an official walked past, designating each person as either Army or Marines. The men on either side of Tom were sent into the Marines; Tom was sent to the Army. Knowing now what the Marines went through in Vietnam, Tom considers that to be one of luckiest days of his life.

Tom went to Basic Training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, and from there, he went to Advanced Individual Training (AIT) in artillery at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. After AIT, Tom received orders for Vietnam—he would be replacing artillerymen who had completed their tour of duty and were returning to the States. (A tour of duty in Vietnam was 12 months, except for Marines, who had a 13-month tour.)

When Tom completed AIT, he boarded a plane and headed to Vietnam with no idea where in Vietnam he was going or what unit he would be assigned to once he arrived. He was on his own.

Tom landed in Cam Ranh Bay, Republic of South Vietnam, in February 1967, and was immediately assigned to the 90th Replacement Battalion. After a couple of days, an Army sergeant told him he would be permanently assigned to the 1st Battalion, 40th Field Artillery Regiment (1st/40th), located at Dong Ha, near the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between South and North Vietnam. The sergeant also told him, “You don’t want to go there.” When Tom reached Da Nang on his way up to Dong Ha, he spoke with a Marine Gunnery Sergeant (“Gunny”), who asked him where he was going. Upon hearing Tom’s response, Dong Ha, the Gunny told him, “You don’t want to go there.” The 1st/40th Field Artillery was assigned to support the 3rd Marine Division in operations around the DMZ, so when Tom arrived he was greeted by a Marine lieutenant who told him, “You don’t want to be here.” The problem was, Tom was there, and there was nothing he could do about it.

Tom was assigned to gun #1 of Charlie Battery. The battery consisted of six M108 105mm self-propelled howitzers, each of which had a crew of six and could accurately fire a thirty-three pound explosive projectile up to seven miles. As a replacement, Tom had to fit into a gun crew that already knew each other well. His gun’s sergeant, Sergeant Martin, told him, “If you listen to me, you’ll get out of here. If you don’t, you won’t.” The choice was obvious, if Tom wanted to survive, he had to listen and learn.

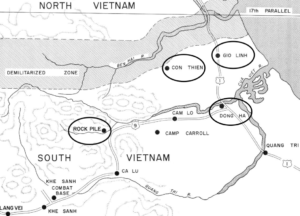

Although the 105mm guns were self-propelled, they executed their fire missions from fixed firebases located in places close to the DMZ like Dong Ha, Con Thien, Gio Linh, C-1, Ca Lu, and the Rock Pile. Each gun fired from a parapet (dugout position), surrounded by sandbags, at a target they could not see. Charlie Battery forward observers gave map locations to the fire direction center, which then calculated the charges to be used and the angle needed in order for the projectiles to reach their targets. The gun crews then trained their guns on the locations identified by the observers. While this allowed them to pour precision fire on enemy positions, it also made them static targets for North Vietnamese mortar, rocket and artillery attacks. As a result, they were in constant danger of being killed by North Vietnamese fire.

Charlie Battery’s proximity to the DMZ and North Vietnam also put them at great risk. Tom notes that Army Intelligence (G-2) warned them repeatedly that they might be overrun. Eventually, Tom realized if it was his time to die, there was nothing he could do about it. Accepting that helped him and his fellow soldiers deal with the constant stress.

Around August of 1967, Charlie Battery conducted a fire mission at Gio Linh, located north of Dong Ha on Highway 1, very close to the DMZ. While they were firing, Tom’s M108 took a direct hit from a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) artillery round. The crewmembers did not immediately realize they had been hit. A call came in over the radio, “#1, you are on fire, get out of your gun.” The crew knew, though, that now that they were hit, the NVA would train their weapons on them hoping they would get out of their stricken vehicle so they could be picked off. The gun crew decided to stay inside the gun, thinking it would be safer. Then they heard someone knocking at the rear double doors of the M108 where handlers loaded ammunition into the vehicle. They opened the doors and saw an officer. Suddenly, another NVA artillery round exploded right behind the officer and they were sure he was dead, so they slammed the vehicle doors shut. Then they heard knocking again, this time coupled with “Open the door you son of a bitch!” They opened the door and the officer climbed inside. After the engagement, they learned that an NVA artillery round had hit their vehicle’s engine compartment. The round totaled the M108, which had to be taken out of service. Miraculously, no one inside the gun was injured. If the round had hit twelve inches higher, they all would have been killed.

Incoming rounds weren’t the only things Tom had to deal with. During one fire mission during the rainy season, Tom and his gun’s crew fired for around forty-eight hours straight. Dead tired, Tom climbed down into his bunker to get some sleep. The bunker, which was dug out of the ground and had steel sheets and sandbags on top, was nothing but mud on the floor given the constant monsoon rain. Tom took off his boots and lay on a cot, too tired to move. He was soon awakened by a rat crawling up his leg, but he was too exhausted to react and just passed out. This memory affects him to this day.

Because the 1st/40th was assigned to the 3rd Marine Division, the Marines treated Tom and his fellow artillerymen like Marines. That meant on occasion, Tom had to participate in night ambush patrols and search and destroy missions. As a trained artilleryman and not an infantry soldier, Tom explains these missions were terrifying. Still, he credits his Army basic training with teaching him what he needed to know to get the job done.

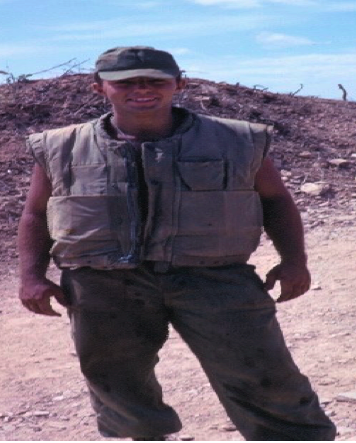

To help prevent casualties, Tom and his fellow soldiers were ordered not to congregate in groups greater than four when moving around their firebases. They also wore flak jackets to protect them in the event incoming enemy rounds threw shrapnel in their direction. Tom wears a Marine flak jacket in this picture. Why a Marine’s issue rather than Army? Because he traded his Army flak jacket to a Marine. The Marines used the firebases to send out patrols, initiate operations and provide perimeter security. One day a Marine approached Tom and asked if they could trade flak jackets. The Marine was going on patrol and he said an Army flak jacket would protect him better than the one issued to the Marines. Tom made the trade. Tom doesn’t know what happened to the Marine—he never saw him again.

When Charlie Battery was out at the remote firebases, they had no way to shower or get clean clothes. Every few days, a truck would take four or five Charlie Battery guys back to Dong Ha for a shower, clean clothes, and a hot meal. Trips like this were a real luxury. In fact, during Tom’s time on the DMZ, he never saw a PX (military store), a USO show, a reporter or even a chaplain. It was just too dangerous.

Vietnam caused Tom and his friends to grow up fast. Often only 19-years-old when they arrived in country, they had to learn quickly to rely on other people. Something Tom valued was that he still had to think for himself. While he followed orders, he knew he could refuse to do anything unethical or illegal. He liked that and felt like that was what set American soldiers apart; they can think for themselves when necessary.

Tom left Vietnam around the end of February 1968, a month after the start of the Tet Offensive. For once, his location by the DMZ worked to his advantage, as the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong concentrated their Tet attacks against cities and towns in South Vietnam, not against units in the field like Charlie Battery.

For its service in Vietnam, the 1st/40th received the Presidential Unit Citation (Navy) 1966-1967, and two Meritorious Unit Commendations (Army) for 1967-1968 and 1968-1969.

When Tom arrived home, he had thirty days leave in Brooklyn to decompress. Then he had to finish the remainder of his two-year Army commitment at Fort Sill in a unit training new artillery officers on what to expect in Vietnam.

Tom was honorably discharged on September 3, 1968. He returned to Brooklyn and his former job at the New York Stock Exchange. He also completed his bachelor’s degree at Brooklyn College, but now he had a different outlook. He no longer valued the money he thought so important when he first started working right out of high school. Now he was just happy to be alive, and he wanted a career helping people, so he turned to healthcare and earned his Master’s Degree in Healthcare Administration. And, he intentionally tried to forget about the war.

The war returned in 2000 once Tom’s children grew up and Tom and his wife had more time on their hands. It first surfaced as diabetes and congestive heart failure—the result of exposure to Agent Orange—and then as PTSD. Tom has dealt with the war by tracking down and reconnecting with other members of Charlie Battery, and by arranging reunions around the country. He’s found that there is no better therapy than meeting with his brothers-in-arms and working through the war’s issues together, just like they did on the battlefields of Vietnam fifty years ago. Tom also wears his Vietnam Veterans hat to remind the American public of those who served and died.

Voices To Veterans is proud to salute Specialist 4 Tom Garvey, U.S. Army, for his distinguished service in Vietnam and for his ongoing efforts to preserve the bonds of friendship among Charlie Battery Vietnam veterans. Tom served our country with honor and courage during time of war, and for that we are grateful! We wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Tom’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

October 1, 2018 @ 8:41 PM

Thank You, Tom!