Major Richard N. Walker, U.S. Air Force (Retired) – Engineering the Cutting Edge of Flight

The U.S. military requires many people with varying talents to sustain its position as the greatest fighting force on Earth. In addition to the soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines engaging with the enemy on the field of battle, it needs countless others in support roles giving those on the front lines what they need to fight and win. It needs cooks and bakers, mechanics and builders, doctors and nurses, truck drivers and training instructors, just to name a few. Another key role is that of the engineer who helps design, develop, test, produce, and provide the technology the warfighters need to do their jobs. That is where Major Richard N. Walker, U.S. Air Force (Retired), steps in. His work over two decades in uniform has given U.S. forces a decisive edge in both combat and the deterrence of war. He is one of the unsung heroes in the success of the U.S. military.

Rich’s father worked as a system engineer for the U.S. Steel Corporation after graduating from Stanford University in 1942 and serving in the Navy during World War II. His mother earned her bachelor’s degree in physics from Bryn Mawr College outside of Philadelphia—she was the only physics major in her class. After working one year at Bell Labs, she helped a friend move to San Francisco, where she met Rich’s father, and they were married. The couple had two children together in California before settling permanently in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where Rich and his sister were born in 1960 and 1958 respectively.

Rich attended Shady Side Academy, a private school located in the Pittsburgh suburbs. The school mandated sports during high school years, so Rich played soccer and tennis and shot for the rifle team. During his senior year, he also picked up backpacking, an activity he continues to enjoy. To keep money in his pocket, he mowed lawns for people in his neighborhood.

Rich graduated as the salutatorian of his class in June 1979. With the final moon walk just seven years before and space shuttle flights already on the horizon, Rich wanted to pursue a career in aerospace engineering so he, too, could be part of exploring space’s new frontiers. Given that goal, he narrowed his college choices to two universities with outstanding aerospace engineering programs: Stanford University (his father’s alma mater) and the University of Colorado Boulder. To help pay for his schooling, Rich decided to apply for a Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) scholarship, where his education expenses would be covered in return for a military service commitment upon graduation.

The decision to apply for an ROTC scholarship made his college selection decision both easier and more difficult at the same time. In the aftermath of the Vietnam War, Stanford had terminated its ROTC program, so Rich would have to find another way to pay to attend. In contrast, Colorado had Navy and Air Force ROTC programs, both of which he was interested in. Because his father was a Navy veteran, Rich not surprisingly inquired into the Navy’s program first. When the recruiter asked Rich what he wanted to do, he said he wanted to work with airplanes and spacecraft. When the recruiter replied that the Navy put its new officers on ships, Rich headed for the Air Force recruiter. He told Rich working on planes and spacecraft would be no problem, so Rich applied to the Air Force ROTC program and was accepted.

Even with a way to pay for his education at Colorado assured, Rich was still undecided about which university to attend. Although Colorado had a top ten aerospace program, there was something about a degree from Stanford that still beckoned to him. Then he visited a friend’s house and spoke with the friend’s father, who was a judge. The judge told him to take the ROTC scholarship at Colorado and get an advanced degree from Stanford down the road. That advice resonated with Rich, and he began classes at Colorado in the fall of 1979.

During Rich’s senior year, retired Brigadier General Robin Olds visited Rich’s ROTC unit and spoke with the officer candidates. General Olds was a storied fighter pilot who fought in World War II and the Vietnam War. He was also a triple ace, having shot down a combined total of seventeen enemy aircraft in the two wars. He told Rich and the other ROTC students that their job was to prepare for war. Moreover, he told them that if war comes, they need to do everything they could to participate in it because it might be their only chance to do what they’d been trained to do. The general’s advice reminded Rich of his father, who had volunteered for sea duty onboard the heavy cruiser USS Los Angeles (CA-135) during World War II after initially being assigned to work in shipyards. The general’s words and his father’s example guided and motivated Rich for the rest of his Air Force career.

Rich graduated from the University of Colorado Boulder with a bachelor’s degree in aerospace engineering in May 1983. Because he was a distinguished graduate for his ROTC class, he also received a commission as a second lieutenant in the regular Air Force, while his ROTC classmates received their commissions in the Air Force Reserve. As he did not have to report to his first duty station until September 1983, he spent the summer visiting friends.

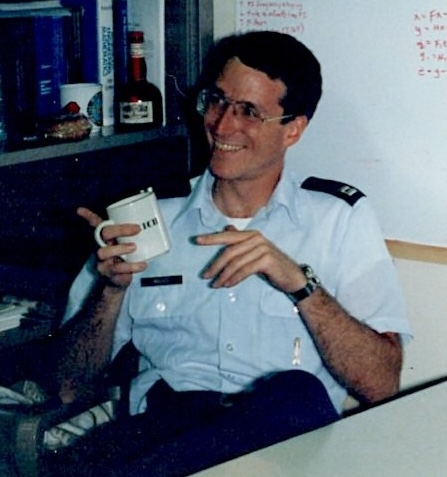

In September, Rich reported as ordered to the Air Force Rocket Propulsion Laboratory located on Edwards Air Force Base (AFB) in the California desert. The lab was the hub for research and testing of the rocket engines for U.S. intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), space launch vehicles, and air-to-air missiles. In the 1960s, it was also the site for testing the rocket engines for NASA’s Apollo space program. Rich’s initial assignment was as a general acquisition research engineer working on solid propellant rocket motor design concepts for ICBMs, strap-on booster rockets, and other space vehicle launch systems. The experience proved extraordinary because he served alongside senior engineers who had worked on the Apollo rocket program. As those senior engineers retired, Rich and other young engineers stepped into their roles, gaining significant practical and project management experience that would otherwise have taken years to obtain. They also developed a strong esprit du corps, all motivated by their common efforts in support of U.S. missile technology and ultimately nuclear détente with the Soviet Union.

Rich promoted to first lieutenant in July 1985. Around this time, he participated in a paint ball fight between his group of junior officers from Edwards AFB and another group from the Los Angeles AFB. Rich was shot by a second lieutenant from Los Angeles in charge of the work surrounding a solid fuel rocket booster for a Titan missile designated to launch large satellites. Six months after that encounter, that officer called Rich about attending a contractor meeting in January 1986 to discuss using the O-ring seals from the space shuttle boosters on the Titan rocket, whose single O-ring seals appeared to be eroding based on recovered boosters. When the program’s colonel asked Rich and the expert with him what they thought of the proposal, they replied that while they were not familiar with the space shuttle O-rings’ performance, they did know that the Titan had not suffered a seal failure in over 100 launches. Moreover, experience with testing the Titan’s type of seal on air-to-air missiles indicated the contractor’s theoretical analysis supporting using the space shuttle O-rings was not a good predictor of success. Accordingly, they recommended against the change.

After the meeting, the colonel accepted their recommendation. One week later, an O-ring failure on the Space Shuttle Challenger destroyed the vehicle shortly after launch, killing all on board. From that point on, Rich’s judgment and recommendations received added weight among his colleagues. He also took on additional responsibility because his boss was called away for a year to assist with the Challenger mishap investigation.

Throughout the time Rich spent working on space-related projects, he served as one of two officers leading research efforts for Small ICBMs—mobile ICBMs that were harder to locate and destroy than their siloed counterparts—and next generation ICBM variants. Because of his ICBM expertise, he was also selected as the ballistic missile research planner on the lab commander’s staff during his final year at the lab.

After mastering the basics of being an Air Force aerospace engineer at the Rocket Propulsion Laboratory, Rich transferred to the Air Force Institute of Technology (AFIT) at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio, to pursue his master’s degree in astronautical engineering with a specialization in structures. He sought the change away from rocket engines because he had observed their development slow over the past few years and wanted to be at the forefront of cutting-edge research. In addition, President Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), which at the time was garnering significant attention and effort, envisioned employing numerous structures in space to shield the United States from ballistic missile attack, so Rich wanted to study controlling space structures.

Rich arrived at AFIT in June 1987 and promoted to captain in July. Over the course of the next eighteen months, he took eighty-eight credit hours of engineering courses covering structural dynamics, structural analysis, and passive and active damping (i.e., reducing vibrations). He also completed his master’s thesis, earning his master’s degree in astronautical engineering (structural dynamics/analysis) in December 1988. As if that wasn’t enough, he graduated first in his astronautical engineering class. In fact, he so impressed the faculty with his work, they invited him to return to AFIT to teach about control and damping systems. First, though, he had to earn his Ph.D. over the next three years—a very ambitious timeline given it usually took five years to complete. On the positive side, he would get to do so at Stanford University, fulfilling the advice he received years before. Better yet, the Air Force would pay for the cost of his studies.

Unfortunately, the timing of Rich’s arrival at Stanford in January 1989 made achieving his Ph.D. within the allotted timeframe extremely difficult. First, the damping program courses he needed were only offered every other year, so he could not take them in time to complete his work. Second, because he started in January, he missed all the fall quarter courses necessary to prepare for his oral boards that were already just a few months away. When he took the boards, he passed his fluid and structural mechanics boards, but not the board covering dynamics and control because he had not taken Stanford’s basic control classes. He took those classes in the fall and passed the related board then, but by then he was falling behind the three-year timeline.

Although Rich might have been able to catch up with the timeline, an issue arose with his doctoral thesis that proved insurmountable. He and his faculty advisors had settled on a theoretical topic for the paper, and Rich began working on it. Then, in 1991 as academic databases started coming online, Rich did a search and found that a research team in Australia had already covered his topic. That meant Rich would have to find a new topic and complete the associated research, and there simply was insufficient time. He asked for an extension given the confluence of the circumstances he faced, but his request was denied. Accordingly, he returned to teach at AFIT in January 1992 without a Ph.D. Despite these hurdles, Rich still wrote a thesis while working full time over the course of his next two assignments, earning the Degree of Engineer, Aeronautics/Astronautics (Dynamics and Control) in September 1994. Still, it was not the Ph.D. the Air Force expected. This shortfall would have ramifications later in Rich’s career.

When Rich returned to AFIT in 1992, he joined the faculty as an instructor and, instead of teaching about rocket and space structures given the experience he gained during his first assignment, taught courses in aircraft dynamics, aircraft handling qualities, and optimization theory. Rich found the ground in his new areas more fertile, especially with President Reagan’s SDI now in the rear-view mirror. As a result of teaching at AFIT, Rich became proficient in the engineering for aircraft performance, which proved timely.

In the summer of 1993, the military dean at AFIT counseled Rich that he could not get promoted at AFIT without his Ph.D. and released him to find a job with one of the acquisition programs located on Wright-Patterson AFB. Finding a position proved difficult because in the peace dividend years after the fall of the Soviet Union in December 1991, new developments were few. Fortunately, the chief engineer for the Joint Primary Aircraft Training System (JPATS) needed someone with depth in aircraft performance and system design, and Rich got the job.

The objective of the JPATS program was to produce the new training aircraft to replace the Air Force T-37 Tweet and the Navy T-34 Mentor basic pilot training planes. Rich’s job was to serve as a system certification engineer, initially helping write and evaluate the contract specifications for the plane. Once the specifications were written, Rich worked with the potential bidders and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), answering questions and making sure to maintain a level playing field for all competitors so no one had an unfair bidding advantage. He performed these responsibilities with skill and integrity—any misstep could have resulted in a challenge to the acquisition and forced the project to be re-bid. He also developed aircraft certification requirements for source selection, evaluated competitor proposals, briefed the Air Force acquisition executive, won acceptance of certification and maintenance plans with the FAA, and became a recognized expert in FAA aircraft certification procedures. The result of his efforts was the Air Force and Navy’s new training aircraft, the T-6 Texan II, which is still in use for basic pilot training today.

In recognition of Rich’s outstanding performance, he promoted to major in 1995. Also in recognition of his work, he was asked by an officer he previously worked with to work at the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency, known as DARPA, as a detailee from the Reconnaissance System Program Office at Wright-Patterson AFB. Rich took the job and reported to the High Altitude Endurance Unmanned Aircraft System Joint Program Office of DARPA in Arlington, Virginia, in March 1996. There he served as the deputy integrated project team lead for a groundbreaking reconnaissance drone program known as Global Hawk, although he also spent much of his time in San Diego at the contractor facility building the drone prototype. The drone was designed to supplement the aging U-2 spy plane and could fly 3,000 nautical miles, loiter for up to 24 hours at 60,000 feet, and return home. Rich was responsible for the drone’s structural design, analysis, and testing, including a bending test of the drone’s wing which was made of a new composite material. He also oversaw aircraft subsystem installation and airframe integration. The Global Hawk program proved its worth when the prototype was employed during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Soon, all the combatant commanders wanted to employ the drone in their theaters of operation.

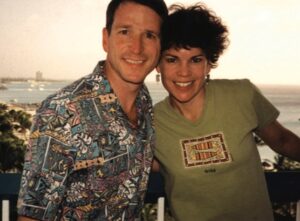

U.S. combatant commanders weren’t the only ones who recognized Global Hawk’s success. In 2000, the program won the Collier Trophy, a prestigious annual award for the greatest achievement in aeronautics or astronautics relating to improving demonstrated performance, efficiency and safety. Rich attended the awards dinner as part of the DARPA and Air Force development team. In addition, the Global Hawk prototype Rich worked on now hangs in the U.S. Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, and the U.S. and other countries still use the production version, formally known as the RQ-4 Global Hawk. To top off the year, Rich met Jamie Baylis at a 2000 New Year’s Eve party. They were married two years later at the Old Presbyterian Meeting House in Alexandria, Virginia.

After a year of working on Global Hawk, Rich shifted to another DARPA drone program known as the RQ-3 DarkStar. This time he served as the Deputy Program Manager, overseeing contracts with the Lockheed Martin Corporation and Boeing to jointly develop a stealth surveillance drone. Rich joined the project after the first prototype crashed, with his job being to identify and fix the problems in the drone’s specifications and help make it operational worldwide. The project faced numerous hurdles, not the least of which was the inability of the Lockheed and Boeing teams to work together. In addition, the aircraft layout—like a flying Hershey bar with only a small forward fuselage—made it difficult to control on takeoff. There were other problems, too. For example, the initial design of the drone did not include navigation lights, which Rich flagged as a non-starter noting they were required and all other U.S. stealth aircraft had them. The companies’ engineers eventually added the lights, but not before labeling them “Walker’s folly.” Despite the contractors’ attempts to correct the other problems with the drone, by 1998 it became clear the DarkStar program was doomed. Accordingly, the Department of Defense shut down the program and transferred the remaining funding to the more successful Global Hawk program. Still, the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum on the National Mall displayed one of the RQ-3 DarkStar drones for several years before the museum was renovated, but the surviving test aircraft is still on display at the Air Force Museum in Dayton, Ohio.

Rich’s experience at DARPA was the best of his career. He had immense responsibility as part of a five-person government team working on national-level programs involving tens of millions of dollars. He even made it as a finalist for the Wright-Patterson AFB engineer of the year. Unfortunately, none of this was enough to overcome the Ph.D. missing from his resume. In fact, the chief military engineer at Wright-Patterson actually called Rich to his office and asked him to explain why he had not earned his doctoral degree. The final blow came when it came time to transfer to Rich’s next assignment. He had done so well at DARPA and been given such stellar performance reviews that he had a chance to be selected for promotion to lieutenant colonel. However, instead of allowing him to extend past his scheduled September transfer date so his current supervisors who knew him well could write his next promotion recommendation, he had to transfer on time to his new command where he would be the newest member of the staff and thus not likely to receive the promotion recommendation he needed. As a result, Rich did not select for lieutenant colonel.

Dismayed but not deterred, Rich learned that the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) might be looking for someone with his qualifications. At the time, the NRO was just beginning to make its existence known to the public. Its function was to develop, launch, and employ space-based sensors in support of U.S. national defense; however, few people knew anything about the NRO or what it did. In fact, when the NRO asked Rich to interview for a job, he could not even be told what the job was because it was so highly classified. When he finished the interview, he was certain he did not get the job because he could not explain how his qualifications made him the best choice because he didn’t know what the job was. He later learned an NRO employee he met at Stanford had recommended him for the position, which he ultimately did not get. Still, he impressed his interviewers so much that they created a new position for him at the Low Earth Orbit System Project Office and brought him onboard the NRO in 1998.

Joining the NRO team proved difficult, especially during the first year, because people guarded information so closely. Rich started out as the Deputy Chief, Integration and Test for a new series of reconnaissance satellites. When his boss transferred, he became the Chief of Test and, later, the Chief Spacecraft System Engineer, where he evaluated production and design issues, recommended resolution plans, and implemented a requirement verification/waiver process for the satellite project. This helped with his integration into the team because his position demanded he be included in the program manager’s inner circle. When the satellite project fell behind schedule, Rich and his team of engineers began shiftwork to provide engineering oversight twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. As Rich was single, he scheduled himself for midnight and weekend shifts so others could spend time with their families during “normal” hours.

Rich’s work culminated with the launch of the satellite in September 2001. Rich directed a sixty-person team in Denver checking out satellite operations. Three days after the satellite launched, terrorists attacked the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Rich found the launch particularly satisfying because the satellite was available to assist immediately after the United States had been attacked.

With the satellite operational, Rich began work on his second satellite project. When the program manager departed, Rich’s boss took over the position as the acting program manager. When he left, too, Rich became the acting chief of acquisition development, assuming an incredible amount of responsibility. His rise in the organization was so fast that during one meeting, the NRO head of finance turned to him and asked, “Who are you?” Rich responded, “I’m the acting acting chief of acquisition,” signaling with the two “actings” how turnover had propelled his ascent.

As the acting acquisition development chief, Rich was responsible for a multi-billion-dollar budget and directed the activities of 300 contractor and government engineers managing a top NRO satellite program. He remained in this position until a permanent chief of acquisition development from the Navy was named, and then he was designated as his replacement’s chief of staff in recognition of his vast knowledge and experience with most aspects of satellite manufacturing and testing. He stayed in this position for eighteen months until he retired from the Air Force in 2003 after twenty years of service. In recognition of his distinguished career and his contributions to the NRO, Rich not only received the traditional Air Force retirement ceremony, but his Navy boss also arranged for him to be “piped ashore” by a Navy boatswain’s mate as is done to honor retiring Navy officers.

Given all the experience Rich gained over his active-duty career, he did not have to search for a job after retiring—employers reached out to him. He settled on an offer from Airborne Technologies Inc., where he was employee number three. Rich was brought on as the senior system engineer and program manager, providing science and engineering technical support to classified government programs. In 2005, he and Jamie added a daughter, Natalie, to their family. Then in 2007, Rich shifted to developing an air-launched electric drone, which took him to places like Yuma, Arizona; White Sands, New Mexico; and China Lake, California, for flight tests. When L3 Technologies purchased Airborne Technologies Inc., he became a senior program manager focusing on unmanned aerial systems. He stayed in this position until he retired in January 2022. Rich and Jamie are now enjoying his retirement in Arlington, Virginia.

As Rich reflected on his long career, he was drawn back to his time at Stanford University when the Gulf War broke out. All the Air Force graduate students with operational experience volunteered to serve in the war. All were denied, just like Rich’s father’s entire Stanford engineering class was counseled against taking combat assignments immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Then as now, senior military leaders recognized engineers like Rich could make far greater contributions to the defense of the United States by developing the advanced systems the warfighters needed to fight and win wars. Recalling Brigadier General Robin Olds’ advice to do all he could to participate in a war should one break out, Rich came to understand that his war involved preparing the United States for potential conflict. He accepted that role knowing that his work helped maintain America’s superiority on the battlefield.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Major Richard N. Walker, U.S. Air Force (Retired), for his distinguished career in the research, acquisition, and development community. Always on the cutting edge, Rich assumed responsibility beyond his years and pushed the development of key defense technologies critical to warfighter training and operations. There is no doubt the systems Rich helped develop gave U.S. forces the tools they needed and saved American lives. We thank Rich for his twenty years of dedicated service and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Rich’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

February 22, 2025 @ 7:29 AM

More great stories about our heroes! Thanks again Dave ! KEep them coming !

February 26, 2025 @ 11:12 AM

Judi, Thanks for reading Rich’s story – I’m glad you enjoyed it!

V/r,

Dave Grogan