Second Lieutenant Bonita Trams, U.S. Army – Operation Babylift Restores Hope

When a young person signs up for the military, they never know what opportunities or hardships lie ahead. Of course, they know basic training will be difficult, but beyond that, their lives depend upon their specific jobs, the places they are assigned, the situations they are placed in, and the people they work with. These factors combined to bring both trauma and triumph to Second Lieutenant Bonita Trams during her ten-year military career. Throughout it all, Bonita remained committed to her dream of serving as an Army nurse and speaking out for the children she was assigned to protect.

Bonita was born in February 1955 on Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana. Her father was in the Air Force, but he was soon out of the picture after proving himself an unfit parent. Rather than raise Bonita in Louisiana, her mother, Beraldine, moved with her to Springfield, Illinois, where they had a large extended family. Beraldine also remarried, and Bonita’s stepfather legally adopted her when she turned five.

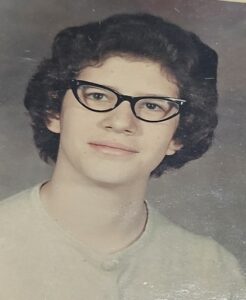

In search of a better school system for Bonita, the family moved to Meredosia, Illinois, a small town about sixty miles west of Springfield. There, Bonita attended Meredosia High School, where she played percussion in the band her last three years. She also had a strong interest in English and learned to keep a journal—something she continues to do to this day. In addition, she took a job waitressing at a local restaurant and saved enough money to buy her own car, a 1957 Chevy Impala, during her senior year.

After Bonita graduated from high school in May 1973, she attended a local business college for one year at the recommendation of her parents. What she really wanted, though, was to become a nurse, so she visited an Army recruiter in July 1974 in nearby Jacksonville, Illinois, to pursue her dream. The Army had the nursing program she wanted, so she enlisted after scoring well on the Armed Forces Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) and passing her physical exam in St. Louis.

Bonita reported for basic training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, in August 1974. There she joined other young women who had enlisted for jobs in the medical field. On the first full day, they were told to rest as other women continued to report. On the second day, they were issued uniforms and given a battery of shots. Finally, on the third day, they were assigned to their barracks and met their drill instructors for the first time. The drill instructors yelled so much Bonita didn’t think they knew how to talk plainly.

Basic training evokes strong emotions for Bonita because she was sexually assaulted there by one of the drill sergeants. She did not report the assault because that meant going through the chain of command and the drill sergeant was part of her chain of command. She also knew the chain of command would believe the drill sergeant rather than her, so she internalized the pain and continued with her training.

Bonita graduated from basic training on schedule and, after taking leave at home, reported to the U.S. Army Medical Center at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, for initial medical training. One of the skills she learned at Fort Sam Houston was how to administer an IV. After the instructors explained the process, they told the students to insert the IV needle on their own. Bonita thought that meant they were supposed to stick themselves, which she did, and it worked. When the instructors saw what she had done, they said that was not what they had intended—the students were supposed to stick the dummies they typically practiced on. However, because Bonita’s self-stick worked, she received a passing grade on the IV skill.

About six weeks into the course, the pain Bonita internalized as a result of her being attacked at basic training became too much for her to deal with. Not knowing where to turn, Bonita attempted to take her own life. Although this normally would have been grounds for her to be discharged, a sergeant said if Bonita could still pass her tests, she would be permitted to continue in the program. Because she so badly wanted to become an Army nurse, Bonita did what she needed to and passed all her tests, successfully completing her basic medical training.

Bonita’s next training stop was the year-long nurse course at the Madigan Army Medical Center at Fort Lewis, Washington. There she learned the skills she needed to be a nurse, including providing patient care, taking vital signs, administering medications, reading x-rays, monitoring medical equipment, and treating and dressing wounds. Initially, the bulk of her instruction involved classroom training; however, during the last eight weeks, she learned to apply her classroom lessons in clinical settings. This included typing and cross-matching blood types, training in operating rooms for two-weeks, and shadowing a nurse around the medical center to better understand her responsibilities. Bonita was also instructed to approach every patient in the hospital as if their treatment were an emergency to ensure they received the timely care they needed.

In April 1975, a unique opportunity arose for what the nursing program’s head nurse called “training on the wing,” meaning training they would never get in school. Bonita was excited to participate, thinking she was going to help transport patients cross-country from Madigan to Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C. Instead of heading east after takeoff, though, Bonita’s C-141 transport plane headed west. Its destination: Saigon. With the North Vietnamese Army closing in on the city, on April 3 President Gerald Ford had authorized the evacuation of orphans from Saigon in what became known as Operation Babylift. U.S. transport planes from around the Pacific participated, delivering last-minute supplies to the beleaguered South Vietnamese military in Saigon and then evacuating U.S. personnel and Vietnamese orphans on the return flights.

The missions into Saigon were dangerous. Although the U.S. was no longer involved in the fighting, South Vietnam was still at war and reeling from what would turn out to be North Vietnam’s successful final offensive to capture Saigon. In fact, the first U.S. Air Force airplane to evacuate orphans from Tan Son Nhut Air Base in Saigon, a giant C-5 “Galaxy” transport plane, crashed after a door failed, killing more than 100 of the over 300 people, including children, on board.

Once Bonita’s plane landed at Tan Son Nhut, things began to happen. She was not permitted to leave the plane nor was she issued a weapon, although some of the crewmembers did carry weapons. U.S. military and embassy staff evacuating from the country came onboard, followed by seventy-nine South Vietnamese children, all under the age of two. Each evacuating American was given an infant to care for on the flight back to the United States. Bonita showed the adults how to poke a small hole in a surgical glove filled with baby formula, cow’s milk, or goat’s milk to feed their assigned baby. This was no easy feat, as most of the babies had only been breastfed and were not used to formula. She also had to teach some of the young military members, all of whom were men, how to change diapers. As they did not have any diapers on the plane, they had to use t-shirts and any other clothing they could find as substitutes. Given the diaper scarcity, they only changed the babies’ diapers when it was absolutely necessary. One soldier who donated his t-shirt told Bonita, “I don’t need my t-shirt back.”

Bonita’s plane spent eighteen hours on the tarmac in Saigon before starting the long journey back to the United States. Many of the babies heading to their new home did not look their age because they were small and malnourished, yet they all were precious. At one point during the trip, Bonita held a baby girl in her arms and didn’t want to let her go. But she had to let go of her and all the others when the flight made stops in Chicago, California, and Tacoma, where the evacuating military members, embassy staff, and babies disembarked.

Operation Babylift turned out to be just what Bonita needed. She had struggled ever since being sexually assaulted at basic training, finding it hard to see anything good in life. Being part of the coordinated effort to bring babies out of South Vietnam’s chaos so they could have a chance for a better life in the United States restored her faith in people. She could once again see goodness and beauty around her, and she had a new-found purpose to go on. As it turned out, Operation Babylift saved more than the South Vietnamese orphans and U.S. evacuees from Saigon—it saved Bonita, too.

Bonita graduated from the Madigan Medical Center nursing program as a registered nurse and accepted a commission in the Army as a second lieutenant. She stayed at Madigan for her follow-on assignment, working on the various hospital floors and in the emergency room when needed, but her primary assignment was in the children’s ward. There she had the difficult job of visiting the homes of children who had allegedly been abused by their parents. Based upon her visit, she would decide whether the child needed to be removed from the home.

On one such visit, Bonita believed a six-month-old boy was being abused by his parents and removed the baby from the home. After a hearing eight hours later, a one-star general military judge invalidated her finding and sent the baby back to his parents. The baby subsequently died. The father, a soldier, was accused in the death and faced trial by court-martial. During a hearing in the case, Bonita was called to the witness stand and, angry with the judge for returning the baby to the parents after she had determined he was being abused, called him an idiot. The judge found her in contempt and confined her until she apologized. For five days, an Army judge advocate (attorney) tried to convince her to apologize. Finally, on day five, she agreed and made another appearance in court. She told the judge, “I apologize for how I said what I said in open court.” The judge replied, “That’s the best apology I’m going to get, isn’t it?” Bonita replied, “Yep,” instead of “Yes, sir.” Deciding there was no more to be gained from the confrontation, the judge simply said, “Get out of my courtroom.” In the end, the father was acquitted because the abuser turned out to be the baby’s mother.

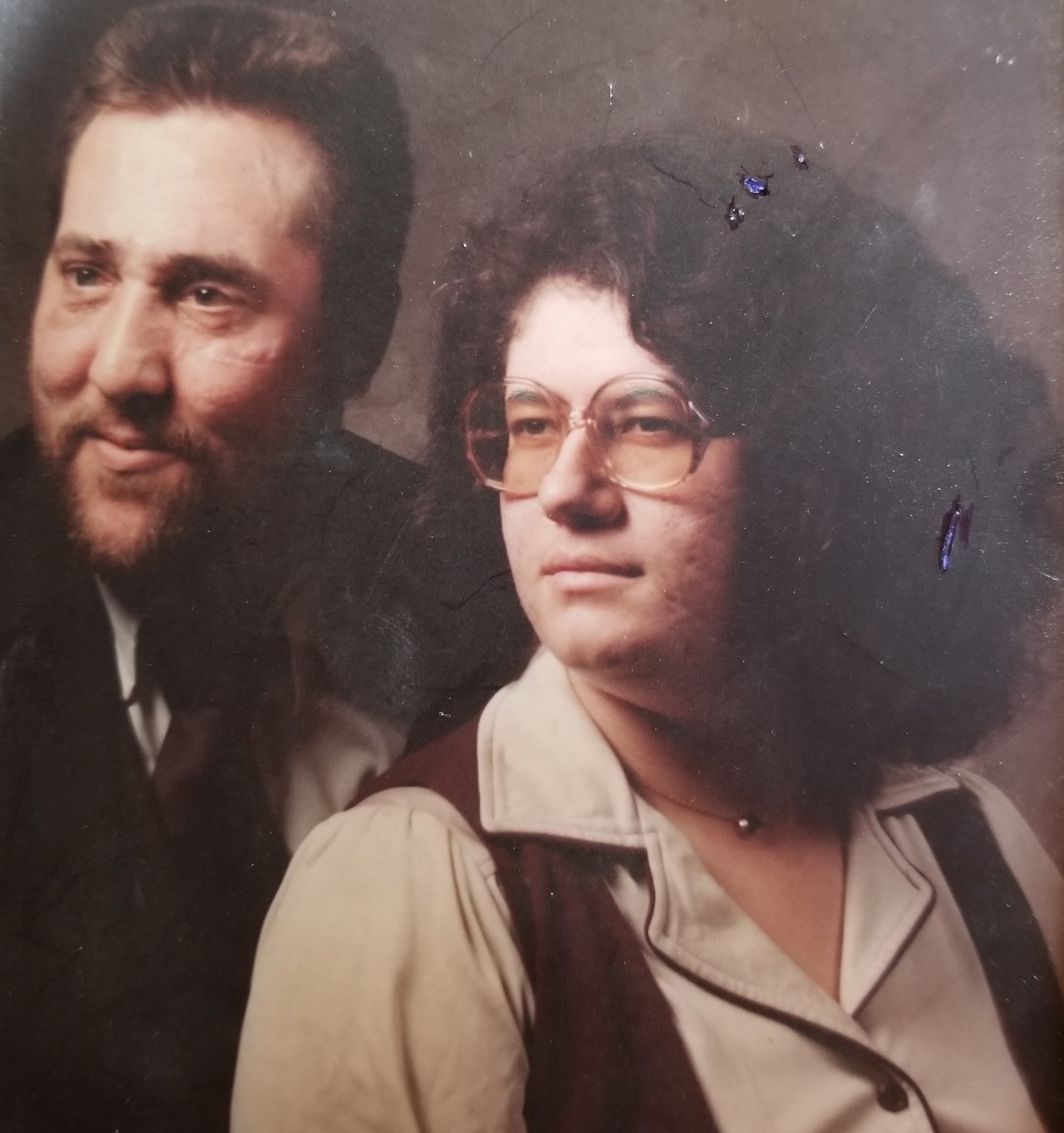

In 1979, Bonita felt it was time to return to civilian life to continue her nursing career. She’d had a run in with a lieutenant colonel who made a disparaging comment about women in the military and Bonita called him out for it. Believing the incident would impact her military career, she returned to Springfield, Illinois, on terminal leave. There she met retired Navy Chief Petty Officer Robert Trams over the Labor Day weekend, and they were married in November. Her discharge from active duty became final in December 1979.

Bonita continued her affiliation with the military in Springfield. She joined the Illinois National Guard, but not as a nurse. That meant not serving as an officer but instead enlisting as a specialist (E-4) and working as the administrative clerk for the 204th Medical Battalion. She was the only woman in the unit and had to earn the respect of the male soldiers, who at times made it difficult for her with sexist behavior and remarks. Also making it difficult was her and Robert’s move to Chicago, requiring her to commute to Springfield for drill weekends with her unit. Still, she worked hard and served out her enlistment, finally returning to the civilian sector for good in 1982.

In Chicago, Bonita worked as a nurse for the North Chicago Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center until her husband passed away on the last day of 1997. Now on her own with her and Robert’s six-year-old son, her stepson from Robert’s previous marriage, and a daughter she and Robert had adopted, Bonita returned to Springfield to be closer to her extended family. She also attended Lincoln Land Community College and Sangamon State University, earning her master’s degree in history. She used her knowledge of history to help people evaluate historic homes and obtain funding to restore them to their original appearance.

At a nail salon in Springfield, Bonita had a chance encounter that took her back to her Operation Babylift flight to Saigon. One of the salon workers had recently visited Vietnam to see where she was born. Bonita and the woman began to talk, and they discovered the woman was one of the babies on Bonita’s flight, which had dropped her off in Chicago. The meeting brought back all the positive feelings Bonita experienced after the original mission in April 1975.

Now fully retired, Bonita is an active member of the Disabled American Veterans (DAV) and the American Veterans (AMVETS) organizations.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Second Lieutenant Bonita Trams, U.S. Army, for her devoted service to our country. Volunteering to serve in the aftermath of the Vietnam War, she helped some of its most vulnerable victims find a new life in the United States. She also advocated for children who were otherwise powerless to protect themselves. We thank her for her commitment and service and wish her fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Bonita’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

January 18, 2025 @ 9:07 AM

Thank you Bonita for your service. And for your perseverance. Good for you for standing up to that judge! Thank you Dave for this portrait of Bonita.

I recently read Kristin Hanna’s The Women – reading Bonita’s story is a reminder that women served in Vietnam in different ways with grit and integrity and paid a price for the rest of their lives, often without recognition.

January 18, 2025 @ 9:12 AM

PS – thanks to Dave for your labor of love that brings recognition to individuals like Bonita who served our country.

February 4, 2025 @ 10:50 AM

Evy – Thanks for reading Bonita’s story! Dave Grogan

January 18, 2025 @ 6:25 PM

What an inspiring story of Bonita Tram’s life. Even though early in her career, she had reason to give it all up, she overcame that and had a great career and held her ground with her head held high. Fate brought her back to meet one of those she brought out of Viet Nam. Heartwarming. God bless you, Bonita, and thank you for your service!

February 4, 2025 @ 10:49 AM

Vevalee – Thanks for reading Bonita’s story! Dave Grogan