AW1 Carl F. Mottern, U.S. Navy Reserve (Retired) – Dedication and Hard Work Pays Off

Everyone has dreams for their life – things they would like to achieve. For most, translating those dreams into reality is the difficult part. It takes hard work, dedication, and sometimes a little luck. Without those elements, dreams stay just that. Aviation Anti-Submarine Warfare Operator First Class Carl F. Mottern, U.S. Navy Reserve (Retired), wouldn’t let his dreams die. When others dropped out because the barriers seemed insurmountable, Carl redoubled his efforts and kept at it, never giving up. His determination made leaders take notice and drove him to success as a search and rescue swimmer and Naval aircrewman. This is his story.

Carl’s father, Frank Mottern, was a crew chief on a B-24 Liberator bomber during World War II. An ear drum condition prevented him from going overseas, so he served in a training role at the Aerial Gunnery School located at Harlingen Air Base in south Texas. Desiring duty overseas, Carl’s father remarked “we fly as high in Texas as they do in Europe”, but the Army Air Corps wouldn’t listen. Finally, in 1945, Army physicians declared his father’s ear drum cured, and he was transferred to Chanute Field in east-central Illinois for B-29 Superfortress crew training. When the war ended with the surrender of Japan on September 2, 1945, his training stopped.

After his discharge from the Army Air Corps in March 1946, Carl’s father returned to Tonawanda, New York, where he found the Bell Aircraft plant he’d worked at during 1942 and 1943 in a stand down. Accordingly, he took a job in 1949 with the Tonawanda Chevrolet Engine Plant, where he worked until he retired in 1985. Carl’s mother, Helgi Halling, was a war refugee from Estonia. Her family fled Estonia after the Soviet Army arrested her father, an officer in the Estonian Army. She and her remaining family members arrived in New York onboard the transport ship General C. H. Muir (AP-142) in 1947. She eventually worked her way to Buffalo, where she met and married Carl’s father.

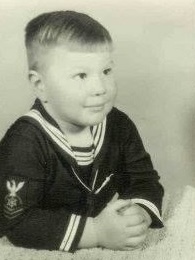

Carl was born in April 1957 in Tonawanda, the first of three children. He attended Kenmore West Senior High School and played junior varsity baseball and club hockey, but he particularly enjoyed the photography club after taking a photography class at school. He also worked throughout his high school years because he wanted his own pocket money. He started with a paper route and moved on to become an emergency dishwasher for the Your Host family restaurant chain, filling in for full-time dishwashers when they called in sick. On weekends, that meant sometimes pulling the 11:00 p.m. to 7:00 a.m. shift, even though he was too young to work those hours. He also worked for Federal Meats, a high-end Buffalo deli with locations in Tonawanda, Buffalo, and nearby Niagara Falls.

By the time Carl reached his senior year, he knew what he wanted to do after high school. He’d heard his father’s and his godfather’s flying stories for years, so he knew his career had to involve flying. He’d also watched Navy helicopters recover astronauts returning from space after their capsules splash landed in the Atlantic Ocean, which he thought looked exciting. His first inclination was the Air Force, but the Air Force could not guarantee he would get a flying job if he enlisted. That left the Navy, so in the fall of his senior year in 1974, he marched to the Navy recruiting office in Tonawanda and told the recruiter, Petty Officer Randy Wulf, “I want to join the Navy right now.”

This was fast even for the recruiter, who first had to verify Carl was a qualified candidate by administering screening tests and determining if he was physically qualified. When everything checked out, he arranged for Carl to take the Armed Forces Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) test and get a more thorough physical, and then drove him home. Carl’s mother saw him get out of the recruiter’s car and once he got in the house, asked him who dropped him off. Carl told her it was a Navy recruiter and that he’d joined the Navy, to which she replied, “You’ll quit that like you’ve quit everything else.” By chance, Carl’s dad pulled into the driveway after work and walked in on the conversation. Carl’s mom told him, “Guess what Carl has done? He’s joined the Navy.” Without missing a beat, Carl’s dad replied, “Good for him. If I were twenty years younger, I’d join with him.” With that, the matter was settled – he had his parents’ support.

As the enlistment process continued, Carl passed his physical and completed the ASVAB test. He was afraid he had not scored well on the test because he was not good at math, but he did well, nonetheless. When Petty Officer Wulf relayed the ASVAB results to him and asked him what he wanted to do in the Navy, Carl suggested Photographer’s Mate, abbreviated “PH”, because the job involved his two loves, photography and aviation. Petty Officer Wulf told him photography was a dead-end job because there was a glut of PHs as a result of the post-Vietnam War drawdown. He suggested as an alternative Naval Aviation Anti-Submarine Warfare Operator, abbreviated “AW”, which would guarantee Carl flying duty. That sounded great to Carl, so on December 20, 1974, he signed the enlistment paperwork at the Military Entrance Processing Station (MEPS) in Buffalo and was sworn into the Delayed Entry Program. That program allowed him to select a future date after his high school graduation to report for active duty. Wanting to enjoy the summer of 1975 still as a civilian, he selected September 8, 1975.

Carl graduated from Kenmore West Senior High School in June 1975. He spent the summer having fun, including going out with a girl he’d met during his lunch breaks at Federal Meats, Veronica “Ronnie” Capello. Together they went to concerts, movies, and ball games, packing in as much time together as they could. Then, on September 8, he said goodbye and flew from Buffalo to Chicago for boot camp at Recruit Training Command on board Naval Station Great Lakes, just north of Chicago. He arrived in the middle of the night, so his in-processing did not begin until the next morning.

When morning arrived, Carl and the other new recruits were escorted to the galley for breakfast. While waiting in line, he heard someone behind him hurling insults about guys from Kenmore. Unable to ignore it any longer, Carl turned to see who was verbally assailing him and saw a friend, Don Wojnar, who had graduated from high school but had joined the Navy a month before Carl. Don would have a long career in the Navy, eventually retiring as a Chief Petty Officer (E-7).

Carl found boot camp relatively easy, primarily because he wanted to be there. Others did not, evidenced by Carl’s company shrinking in size from about ninety members at the beginning of training to around seventy-five at the end. Still, it was not all rosy. During one inspection, Carl’s company commander, a former boxing champion, smacked him so hard it knocked his jaw out of place. Carl said nothing about it, hoping it was an isolated incident, but he never forgot it. Either did his company commander because at graduation he announced to the company while looking directly at Carl, you can file a complaint if you think you’ve been abused, but that means you’ll just have to stay here longer. Carl had no intention of doing either, so he let the incident pass.

Carl graduated from boot camp on Friday, November 7, 1975. His parents drove from Tonawanda for the ceremony and spent the weekend with Carl touring the city of Chicago. When they started their trek back to New York, they got caught in the same winter storm that sank the Edmond Fitzgerald on Lake Superior on November 10, as did Carl, who remained onboard Naval Station Great Lakes until November 13. Carl then took leave to fly home to visit Ronnie and spend some more time with his parents before he had to report to his next duty station. As he walked through Chicago’s O’Hare Airport in his Navy uniform, a man working at a shoeshine station asked Carl if he wanted a shine. With money in his pockets and feeling like the richest man in the world, he sat down for a shoeshine and basked in the reality that someone else was shining his shoes for the first time since he’d arrived at boot camp.

After spending two weeks at home, Carl reported to AW “A” school in late November 1975 onboard Naval Air Station Memphis in Millington, Tennessee. There he began to learn about the science of detecting and attacking enemy submarines lurking beneath the oceans’ surface. Each week he learned new material and had to pass a test on Friday to continue in the training. Unexpectedly, his difficulty with math caught up with him because the curriculum included working with the formulas necessary for fighting submerged submarines, equations for calculating radar parameters and capabilities, and salinity computations to determine how sound propagates through ocean water. Although he failed some of the Friday tests, he was determined to succeed, so his instructors permitted him to retake the necessary classes until he had sufficient command of the material to pass the Friday exams.

Carl was not the only person retaking some of the course work. There were also Iranian students in the class who had repeatedly taken the classes and were so well-versed in the material, they tutored the American students during the week. On Friday, though, they failed the tests because they did not want to go back to the Shah’s navy in Iran. As long as they remained in the school, they were permitted to stay in America, and some of the students took full advantage of that option. The Iranian students’ fears were well-founded, because less than three years later, the Shah of Iran was overthrown during the Iranian Revolution.

Carl graduated from “A” school on March 25, 1976. For his follow-on assignment, he requested duty on helicopters rather than fixed wing aircraft because he wanted to do rescues at sea like the rescue swimmers he’d seen recovering astronauts on television. His determination proved convincing, and he received orders to HS-1, the SH-3 Sea King helicopter Readiness Air Group (RAG) training squadron located onboard Naval Air Station, Jacksonville, in Jacksonville, Florida.

Wanting to save his leave so he could marry Ronnie later in the summer, Carl reported directly to HS-1 from Millington without taking any time off. He arrived before the next round of training was to begin, so he was escorted around to meet the instructors. When one of the instructors, a First Class Petty Officer (E-6), asked where he was from, Carl told him Tonawanda. The instructor replied, “I jumped off the Grand Island Bridge there!” Carl remembered his father commenting about the event when he was about six years old, stating “some nut jumped off the Grand Island Bridge.” Now Carl knew the nut – he was Petty Officer Al Sloniker. He’d done it on a bet and had friends in a boat on the Niagara River below the bridge waiting to pick him up. He was arrested afterwards, but had since channeled his desire to jump in the water into a career as a Navy Search and Rescue (SAR) swimmer. He and Carl hit it off and became lifelong friends.

Although Carl had his heart set on becoming a SAR swimmer, he had a lot of skills to master first. To begin with, he was not an experienced swimmer, so he struggled through the first class. At the end of instruction, he had to pass a practical SAR swimming exam where he was dropped into a rescue scenario with various victims. He had to prioritize those he helped and then use the correct procedures in doing so. He failed, as did about forty percent of his class. The difference between Carl and most others was he was committed to success. As with the “A” school math classes, he convinced a board of instructors he wanted to be a SAR swimmer and would put in the necessary work to make it happen. The board gave him another chance.

When the next SAR class started, Carl sat up front. The instructor, Petty Officer Sloniker, addressed the class and said, “Do you see this guy in the front row? It’s Carl Mottern. He’s here because he wants to be here. I know he will pass with flying colors.” Petty Officer Sloniker’s faith in him gave Carl all the boost he needed. Not only did he pass the practical exam with flying colors, but he also did so on the part of the SAR test he had not taken before. When he finished on June 11, 1976, Petty Officer Sloniker told him, “Congratulations, you are a SAR swimmer.” It was one of the proudest moments of Carl’s life. The training then culminated with a live SAR exercise jump into the St. Johns River. Not only was it Carl’s first live SAR jump from a helicopter, but it was also his first ride in a helicopter period!

Carl had just one day to celebrate before heading off with his SAR classmates and some newly arriving pilots to Naval Air Station Brunswick, Maine, for Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) training. This training taught Carl how to react in the event he was ever captured by enemy forces. It began with his cadre’s arrival at a camp where they learned they had been captured by the People’s Republic of North America. Carl was tossed onto a flatbed truck with another prisoner landing on top of him. That prisoner was a big Naval Academy football player whose size and weight made it hard for Carl to breath. Once they arrived at their destination, the captors slapped Carl and the other prisoners around, blew smoke in their faces, stripped them naked and put them in a cell, and deprived them of both sleep and food. The ordeal seemed so real, soon all the prisoners forgot it was training. At the end, they were all lined up in formation and told to turn around toward the camp’s guard tower. As they did, an American flag unfurled downward and the Star-Spangled Banner began to play. There was not a dry eye among the participants – they had survived!

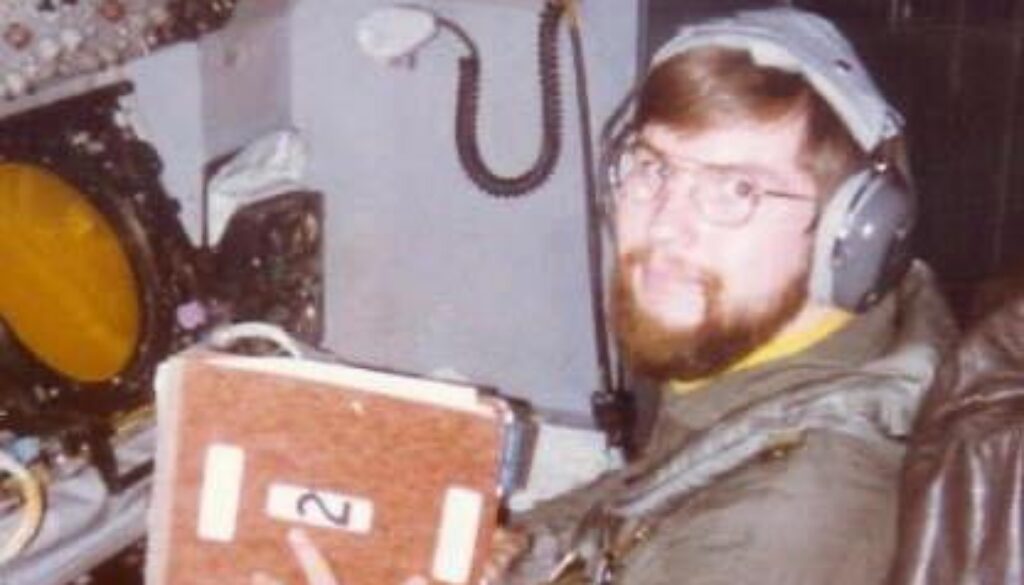

Again, Carl had little time to celebrate. After a hot meal at the Naval Air Station Brunswick galley, Carl and the other trainees returned to HS-1 in Jacksonville to begin the flight phase of their training. Now Carl studied anti-submarine tactics and learned how to use the SH-3 Sea King helicopter’s sonar and radar equipment by practicing on simulators. He put what he learned into practice by flying on SH-3s off the coast of Florida in the Mayport operating area (OPAREA), using the helicopter’s radar to detect ships and dropping sonobuoys and dipping the sonar sensor in the ocean to detect and track submerged submarines. During the flights, his instructors set off inflight emergencies by doing things like tripping circuit breakers to teach him the correct way to respond and not to panic. They drilled him with verbal questions to ensure he knew his responsibilities and equipment inside and out. He also learned to control the helicopter from the rear station and practiced ditching procedures in case the helicopter had to make an emergency water landing.

The training was intense and participants were not permitted to take leave until they had completed all elements. That created a slight problem for Carl as he had proposed to Ronnie and their wedding date, August 21, 1976, was fast approaching. When Carl could wait no longer, he put in special request chit to ask off for Friday, August 20. His instructor, AW1 Larry Bryant, who had himself survived a helicopter crash at sea earlier in the summer, reminded Carl leave was not authorized during training periods. He also reminded Carl if the Navy wanted Carl to have a wife, the Navy would have issued him one. Yet despite that hard exterior, Petty Officer Bryant had a soft spot and authorized Carl’s leave. Accordingly, Carl flew to Buffalo after work on Thursday, August 19, got married on Saturday, August 20, and brought Ronnie back to live with him on Sunday, August 21. Then it was back to training on Monday morning!

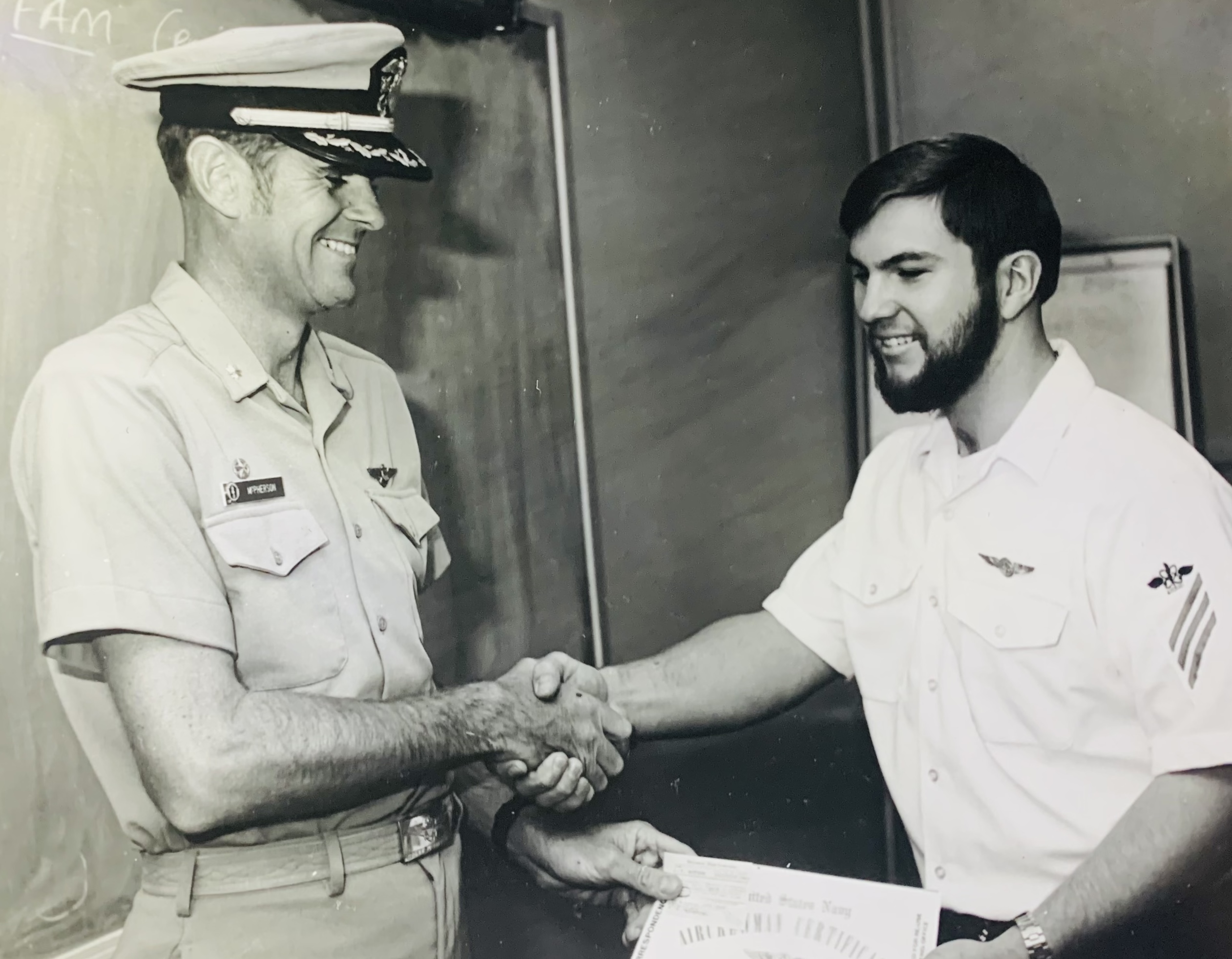

On November 5, 1976, Carl completed the last phase of his training and was officially designated a Naval Aviation Anti-Submarine Warfare Operator. He was now authorized to wear the wings of a Naval aircrewman on his uniform, which Ronnie pinned on him at the ceremony. Then, with his training complete, he walked across the hangar to his first operational SH-3 Sea King squadron, the Red Lions of HS-15. He was assigned to the Aircrew Division, working for the division chief, AWC Ken Muller. Chief Muller told him, “I hate to tell you this, but before you can start work in the division, you’ve got to work in the 1st Lieutenant’s Division. You’ll be thankful for this later.”

Working in the 1st Lieutenant’s Division was another way of saying the new guys must pay their dues. Carl and another new arrival, Airman Joe Brill, had to work in the coffee mess, clean toilets, mop and wax floors, and generally keep the squadron spaces looking good. Occasionally, AWC Muller would grab Carl and take him for a flight just to give him a break. Finally, when Carl’s time was up, he returned to the Aircrew Division and was ready to go.

The first opportunity for Carl to do just that came in January 1977 when he was selected to crew one of three helicopters training at the Atlantic Undersea Test and Evaluation Center (AUTEC) range off the coast of the Bahamas. There the three helicopters got to practice finding and chasing submarines and even dropping exercise torpedoes to simulate an attack. After each day’s flights, they returned to the base on Andros Island where they enjoyed snorkeling, scuba diving, fishing, great seafood, and even a few beers.

With that training under their belts, Carl and the other HS-15 helicopters and crews were ready to start working up on the aircraft carrier USS America (CV-66) in preparation for the ship’s next deployment. As the America was getting ready to come out of the yards in Portsmouth, Virginia, and the squadron was in Jacksonville, Carl and some of the other members of the squadron flew as part of an advanced party to Virginia to board the ship there. When Carl saw the ship at the pier for the first time, it was so giant he was sure he would get lost onboard. Soon, though, he settled into a routine as he became familiar with the ship and how to live onboard.

Once the ship got out to sea, all the fighters and reconnaissance aircraft flew onboard to begin refreshing their carrier landing and takeoff skills. Included among those aircraft were the SH-3 Sea Kings from HS-15. On the second day of flight operations, Carl was in a helicopter flying some distance away from the America conducting plane guard duties. That meant if an aircraft crash landed in the water, Carl’s helicopter would be the first responder responsible for rescuing the downed pilot and aircrew. During a break in the flight operations cycle when no planes were flying, the America suddenly called “man overboard.”

Carl could feel the adrenaline in his veins. Here he was, in only his second day at sea, and he was going to have to go into the icy Atlantic Ocean to rescue a sailor if they were lucky enough to find him. He slipped into his wetsuit as the SH-3’s pilot guided the helicopter to where the sailor should be. When they spotted him, the pilot brought the helicopter down to within ten feet of the water and Carl jumped in the save him.

When Carl found him, he turned out to be “Oscar”, the dummy used in man overboard drills. Surprised but thankful, Carl helped hoist Oscar onboard the helicopter for the return flight to the America. Once onboard, Carl was taken to sick bay to make sure he was okay, especially after being exposed to the elements. There he was told the ship’s commanding officer, Captain Robert B. Fuller (a former POW in Vietnam), said he had done a great job and that since he had successfully conducted a simulated rescue, he was entitled to a simulated brandy (had it been a real rescue, he would have received a real brandy).

The America continued workups throughout the spring of 1977 until it sailed to the southern Atlantic Ocean to conduct operations with the Brazilian Navy. This was exciting for Carl for several reasons. Not only did he get to conduct helicopter operations throughout the period from June 10 through July 19, but he also got to visit Rio De Janeiro and Salvador in Brazil and become a “Shellback” after participating in the crossing the line ceremony when the ship crossed the equator. Carl earned his Shellback certificate, signed personally by Captain Fuller, which he still proudly displays. As if that wasn’t enough, he promoted from Airman (E-3) to Petty Officer Third Class (E-4) on June 16 in recognition of the significant experience he’d gained through his training and operations with the squadron.

Once the America returned to Norfolk and HS-15 returned to Jacksonville on July 19, Carl took two weeks leave. That’s when he found out Ronnie was pregnant with their first child. Unfortunately, on September 29, he had to depart on America again, this time for a six-month deployment to the Mediterranean Sea. Although this was a peacetime deployment, the Cold War with the Soviet Union kept tensions high, especially during interactions with Soviet forces. This occurred in early October, when Soviet Tu-95 “Bear” bombers harassed U.S. ships operating in the Atlantic. Because Carl and HS-15 were at the pointy end of the spear when it came to locating and defending against Soviet submarines, they had to be at the top of their game twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.

As the incoming aircraft carrier to the Mediterranean Sea and the U.S. Sixth Fleet, the America assumed operational responsibilities from the outgoing aircraft carrier, USS Independence (CV-62) on October 8, 1977. As part of the turnover, HS-15 launched a helo with Photographer’s Mate Jeff Dubose onboard to get a photo of the two massive aircraft carriers anchored near each other in the Bay of Cadiz off Rota, Spain. Also in the photo was the USS Detroit (AOE-4), a supply ship previously commanded by the CO of the America, Captain Fuller. As Carl was the squadron’s camera custodian, Jeff DuBose gave him a copy of the photo.

Over Christmas, one of Carl’s best friends in the squadron, Tom Hayes, took leave to be home with his wife who was ready to give birth. With his own wife now eight months pregnant, Carl wished Tom good luck and told him to send a telegram when the baby was born. During the first week of January 1978, the squadron CO tracked Carl down and told him his wife had a baby girl. Carl was concerned because that would be almost a month early. He looked at the telegram and discovered it was Tom’s new baby, not his, and told the CO. When the CO again tracked Carl down in February to tell him his wife had a baby girl, he smiled and asked Carl if he had the right baby this time.

About the same time Tom’s telegram arrived, HS-15 flew supplies to a burning Indian merchant ship, the Jagat Padmini. The freighter was carrying naphtha, a highly combustible petroleum product. Carl’s helicopter flew right over the burning ship taking photos, a dangerous mission considering the ship could have exploded at any moment. On January 9, the crew of the Jagat Padmini had to be evacuated by the USS Nimitz (CVN-68), the USS South Carolina (CGN-37), and the USS Bigelow (DD-942), with the USS Nimitz losing a helicopter in the process. Fortunately, no one on the helicopter was killed.

A distinguished visitor, an Assistant Under Secretary of the Navy related to then-President Jimmy Carter, also visited the ship during the deployment. When it came time for him to be flown off the ship to visit the USS Howard W. Gilmore (AS-16), a submarine tender in La Maddalena, Italy, Carl was part of the aircrew on one of the two HS-15 helicopters flying the mission. Once they landed at Naval Support Activity La Maddalena and boarded the tender, Carl and a crewmember from the other helicopter, AW3 Chris Webber, went to the galley to get some chow. While standing in the chow line, Carl saw a friend of his from high school, Electronic Technician Third Class Joe Cmor, who grew up just three blocks from Carl’s house. After eating, Carl and Chris, who were wearing their green flight suits, walked around the tender. As they did, they saw a submarine tied up alongside the Howard W. Gilmore and decided to see if they could get a tour.

In pursuit of their tour, they crossed over to the submarine, the USS Skipjack (SSN-585). When they arrived on the quarterdeck and made their request, the watch summoned a Lieutenant Junior Grade (O-2), who saw their green flight suits and assumed they were officers. He signed them in and personally gave them a complete tour of the submarine from bow to stern, excluding the nuclear spaces. When the submarine’s CO returned from a meeting onboard the tender with the distinguished visitor, he came across the Lieutenant Junior Grade and asked who the visitors were. The young officer responded, “these are the Secretary’s pilots and I’m giving them a tour.” The CO immediately recognized the officer’s mistake and looked at Carl and Chris and smiled. Then he told the Lieutenant Junior Grade, “When these pilots have left the boat, you come see me right away.” Once back at the helicopters, Carl and Chris told their story and it spread like wildfire. Even the squadron’s CO approached them in the ready room onboard America and jokingly asked about how they had impersonated officers.

Two days after the La Maddalena trip, Carl got a great opportunity for some time ashore. One of the HS-15 helicopters had needed some repair work at the Aircraft Intermediate Maintenance Detachment (AIMD) in Naples, Italy. Carl was selected to be part of the aircrew that would pick it up and fly it back to the ship. That meant launching from the carrier on a twin-engine C-1A “Trader” and landing in Naples, where they picked up the helicopter. They then flew it to Naval Air Station, Sigonella, on Sicily, where they waited until they could fly the helicopter back out to the America. While they were waiting, they took a trip up Mt. Etna, Sicily’s active volcano, and stayed in a luxury hotel, the Excelsior.

Two weeks after Carl’s daughter, Regina, was born, Carl’s CO approached him and told him his daughter was ill and he needed to go home. Carl left the ship and flew out of Palma, weaving his way back to Buffalo, where his wife and daughter were staying during the deployment. Once it was clear his daughter would fully recover, Carl said goodbye to Ronnie and rejoined the America in Naples.

When it came time to head home, the America turned over its operational responsibilities to the next newly arriving aircraft carrier, the USS Forrestal (CV-59). The America and the other ships in her battle group then sailed back across the Atlantic, arriving in Norfolk, Virginia, on April 25, 1978. Carl and HS-15 returned to Naval Air Station, Jacksonville, where Ronnie and Regina joined them. During this post-deployment period, operations were relaxed, with time for squadron bowling teams and softball teams. Carl also continued to practice SAR rescues in the St. John’s River and participate in anti-submarine exercises on the AUTEC range in the Bahamas. HS-15 even hosted a British helicopter squadron visiting the United States aboard the British aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal (R09).

Finally, it came time to begin working up for the next deployment. This time, HS-15 would deploy onboard the aircraft carrier USS Independence (CV-62), the ship from which the America had assumed operational responsibilities in the Mediterranean Sea in October of 1977. In preparation for the deployment, Carl and HS-15 participated in the ship’s workups, which meant conducting exercises and flight operations in the Caribbean.

Carl never felt at home on the Independence. The ship was older than the America and had less space for HS-15. The squadron had inadequate storage to stow its equipment and sailors were constantly getting their personal gear stolen. The theft problem was significant enough to keep Carl from bringing his camera onboard because he was afraid he would lose it. As a result, he has no pictures documenting his time onboard the Independence.

As the ship’s June 1979 deployment to the Mediterranean Sea neared, Carl had to make a reenlistment decision. Because Ronnie did not like living in Jacksonville – she wanted to move north – Carl reenlisted in return for orders to VP-8, a P-3 Orion squadron located at Naval Air Station Brunswick, Maine. This meant once he transferred, he would no longer be flying on SH-3 Sea King helicopters, but instead on the long-range four-engine Lockheed anti-submarine and surveillance plane used by the Navy since the 1960s. Before he could begin his new assignment, he had to deploy with HS-15 on Independence until his transfer date arrived.

That changed in June when HS-15’s Executive Officer (XO) approached Carl and told him he did not have to make the deployment. The XO said Carl had worked hard at the squadron and had earned the right to stay behind. While this was welcome news because he would not have to leave Ronnie and Regina, he also felt guilty because it would leave his squadron short-handed. Carl’s XO told him not to worry about that – the squadron would make it work. He then bid Carl farewell and sent him on temporary duty to HS-1, where he would work until it came time for him to report to VP-8 in Brunswick.

Carl’s welcome at HS-1 did nothing to alleviate his guilt. When he checked in with the personnel chief, the crusty sailor announced HS-15 was “dumping its trash” on him. He then called the Operations Officer and said “I’m sending you someone to take care of for a while”, which turned out well for Carl because the Operations Officer was a former shipmate from HS-15. The Operations Officer gave Carl some real work, including flying as the sole crewmember for pilot trainees and serving as aircrew for fifty pilot trainee water landings (the SH-3 Sea King helicopter has a boat hull fuselage that permits water landings). The fiftieth trainee water landing was Carl’s last flight on a U.S. Navy helicopter.

In September 1979, Carl began the training pipeline that would eventually take him to VP-8. That meant reporting to the P-3 training squadron, VP-30, in Jacksonville to learn about his new aircraft. He arrived a few days after his son, Michael, was born on September 4, 1979. His training focused on radar so he could serve as a radar operator onboard the P-3, instead of being a sonar operator and rescue swimmer as he had been on the SH-3 Sea King. He completed his training on Friday, December 14, 1979, the same day HS-15 arrived back in Jacksonville after its six-month deployment on the Independence. That night, Carl and Ronnie hosted a big party for all of Carl’s returning shipmates. The movers came the next day and Carl, Ronnie, Regina, and baby Michael started the 1,300-mile drive to Brunswick, Maine, with an intermediate stop in Buffalo for the holidays.

Carl checked into VP-8 on January 7, 1980. Although he and Ronnie really liked Brunswick, Carl’s tour did not go as well as it could have. To begin with, Carl was now a senior Second Class Petty Officer (E-5) who had done all his time on helicopters. Due to his seniority, he passed up all those junior to him even though their experience was on the four-engine P-3. This created resentment among the junior sailors. To alleviate the situation, Carl was assigned to the training division, which proved to be a good fit. He also got to deploy on a P-3 to Rota, Spain, and Lajes, Portugal, just before Christmas, hunting Soviet diesel submarines in the Mediterranean and ballistic missile submarines in the Atlantic. The deployment was fun except it created resentment among the enlisted aircrew because the officers had arranged for their wives to meet them in Lajes, while the enlisted aircrew had no such opportunity. Carl, for example, spent Christmas in 1980 in Lajes reading a book in his barracks room.

Carl’s youngest child, Frank, was born in March 1981 when Carl was home on a four-day “R&R” break from a deployment to Rota. The baby was born prematurely, so Carl asked for permission to remain in Brunswick to help Ronnie with their newborn and their other two children. When his XO in Rota denied his request, Carl returned to Rota with his crew. He also retrieved a request to extend with the squadron and tore it up. When his XO questioned his actions, Carl told him it was clear to him the squadron did not value him or his family. He avoided the XO from that point on.

Carl completed his tour with VP-8 and then looked for shore duty in Brunswick so he could stay at home with his family without having to deploy for a few years. His detailer, however, told him nothing like that was available. Seeing no other viable options, Carl told his detailer he would take orders as a recruiter provided he could be guaranteed an assignment in Buffalo, New York. Always short on recruiters, the detailer jumped at Carl’s offer and sent him to Buffalo on recruiting duty in January 1982 after he completed Recruiting School in December 1981.

Recruiting duty proved brutal. Although Carl was an excellent recruiter, the pressure to make monthly recruiting goals never ended. To meet those goals, he had to start early in the morning and work late into the night and on weekends. He had to do presentations at schools, track down signatures from both parents for recruits under eighteen even if the parents weren’t in the picture, give recruits rides home, and meet with parents at all hours of the day and night. After each successful month, the goals reset and he had to start all over again on the next month’s quota. The only real benefit of the tour, in addition to promoting to Petty Officer First Class (E-6), was Carl’s and Ronnie’s children got to spend lots of time with their grandparents, something that would have been impossible had Carl taken orders to another squadron.

As Carl’s enlistment drew to a close in early 1985, the XO of the Naval Recruiting District offered to extend Carl in his current job. She could not, however, promise Carl would make Chief Petty Officer (E-7). More important, Ronnie didn’t want to move anymore. She liked where they lived and wanted to settle down. Accordingly, on May 5, 1985, Carl was discharged from active duty in the Navy.

While Carl’s active duty career had ended, his Reserve career was just beginning. A friend of his from HS-15, Tom Hayes, recommended he try VP-93, a Reserve P-3 squadron located at Naval Air Facility Detroit onboard Selfridge Air National Guard Base. This worked great for Carl as it would allow him to pursue a civilian career and keep his family in Buffalo, while still serving in the Navy. He made it official on May 16, 1985, enlisting in the Reserves after a break of only eleven days since his discharge from active duty.

VP-93 made the Navy fun again. Carl drilled one weekend each month and an additional two weeks each year, plus as many extra drills and active duty periods as he could get, honing his Navy skills. His duties took him to Hawaii, the Mediterranean, and the Caribbean, not only hunting Soviet submarines, but also searching for drug smugglers trying to bring illegal drugs into the United States by sea. Even drilling proved easy because the squadron flew a plane from Selfridge to Buffalo to pick Carl up. Such pickups, which were routine for squadron members, served the dual purpose of giving the P-3 pilots the cross-country flight time they needed and alleviating the need for the aircrew to take off time from their civilian jobs to fly or drive to Detroit.

Even more important, the squadron members were tight with one another, just like the camaraderie Carl experienced at HS-15. They looked out for one another and cared about each other’s families. If someone needed a place to stay when they came into town, they opened their doors to each other rather than requiring them to stay in a hotel. Carl enjoyed the duty so much, he told himself he would stay with VP-93 until they forced him to leave.

Unfortunately, in 1994, VP-93 was slated to be disestablished and Naval Air Facility Detroit closed as part of the post-Cold War drawdown. Accordingly, in March 1994, Carl transferred to another Reserve P-3 squadron, VP-64, at Naval Air Station, Willow Grove, in Pennsylvania, but it wasn’t the same. Not only did he have to drive 375 miles to Willow Grove for each drill weekend, but he also learned he was not selected for Chief as part of the 1995 promotion cycle. As a result, Carl retired from the Navy Reserves on February 1, 1996, ending his Navy career. After the ceremony, he reminded his mother of what she said in 1974 when he told her he was enlisting in the Navy. “You said I would quit, and I never did.” His statement closed a loop that had been open for over twenty years.

Now out of the Navy, Carl focused on his civilian career. He’d been working for the Veterans Administration since 1993, but in 1997 he found exactly the job he’d been looking for. A U.S Customs Service supervisor, Mike Rozyczko, spotted Carl wearing a VP-64 ballcap at an airshow and introduced himself. He told Carl the U.S. Customs Service was looking for customs inspectors and he encouraged Carl to apply. Carl did and, in January 1997, received notice he had been hired to work as a customs inspector for the Port of Buffalo. One of his bosses was none other than Mike Rozyczko and they became the best of friends. Carl’s Navy experience proved instrumental to his U.S. Customs Service success. He especially enjoyed serving on the Port of Buffalo Honor Guard team, which required him to use the drill and ceremonial skills he’d learned in the Navy. Carl finally retired from U.S. Customs and Border Protection on April 29, 2017.

Carl and Ronnie are now enjoying retirement in Buffalo, New York. They keep busy with their three adult children and three grandchildren, who all live nearby, and they travel extensively and take cruises. Carl even began umpiring local baseball games in 2017. He also is a member of the VP-93 Alumni Association and an associate member of the USS Little Rock Association, which sponsors the museum ship in Buffalo’s Naval Park.

One other passion of Carl’s is the USS America Carrier Veterans Association. Carl joined in 1996 after going on a tour of the ship as it was being decommissioned. He soon became one of the organization’s governing board members and has been active in the 600-member organization ever since. Perhaps his most meaningful activity with the Association occurred in 1999 when he reconnected with the former commanding officer of the USS America, now Rear Admiral Robert B. Fuller. Carl interviewed him and wrote several stories about him for the Association’s newsletter, and escorted him when he attended the Association’s reunion in Jacksonville in 2008. There Carl relayed to him the story of when he’d conducted his first search and rescue swim and then-Captain Fuller had announced “simulated rescue, simulated brandy.” Admiral Fuller responded, “Well, how about I buy you that drink now?” Carl notes the opportunity to share the drink with the Admiral was worth the thirty-year wait. After Admiral Fuller passed away in 2019, Carl attended his funeral at Arlington National Cemetery.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Naval Aviation Anti-Submarine Warfare Operator First Class Carl F. Mottern, U.S. Navy Reserve (Retired), for his twenty years of devoted service to our country. His never give up attitude helped him realize his dream of becoming a Navy search and rescue swimmer, setting an example for all those around him. Despite long separations from his family, he went whenever and wherever the Navy called, patrolling the oceans for adversary submarines and drug smugglers and keeping our country safe. We thank him for all he has done and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Carl’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

March 23, 2024 @ 5:13 PM

I so enjoyed this March featured story. I could not stop reading this great story. I love the way you cover all the detailed parts of Carl’s many years of devoted service to the Navy and all that he was trained for as well as all he got to experience while being deployed and also once he was retired from his 20 years of service and joined the reserve. What an amazing life he lead. Reading about the many months away from his wife and children was alarming to me. But, oh, you certainly covered all of the remarkable duties and highlighted and recognized them all. I love the way you write, David. I will look forward to the next month’s story. Thank you for all you share.

March 23, 2024 @ 5:23 PM

Linda – thanks for taking the time to read Carl’s story – I really appreciate it. Career sailors definitely spend a lot of time deployed. Families have to be really strong to make it work. Dave Grogan