Specialist 4 Mark Myers, U.S. Army – Three Things to Count On

It’s often said there are only two things in life you can count on, death and taxes. Ask Specialist 4 Mark Myers, U.S. Army, and other young men during the mid-1960s and they would tell you there was a third – the draft. Mark received his draft notice shortly after his college notified his local draft board he was eligible, thus beginning a chain of events that would lead to him patrolling the jungles of South Vietnam in search of the Viet Cong. This is his story.

Mark was born in November 1945 in Aurora, Illinois, and raised in Naperville, a Chicago suburb located about thirty miles west of the city. His father was a pillar of the Naperville community. Not only was he an attorney and the owner of an insurance consulting business with offices in Naperville and Chicago, but he also served as a Naperville City Councilman and was active in his church. His mother, who had a master’s degree from the University of Michigan, taught English to foreign scientists working in and around Batavia, Illinois. Mark was the third of the family’s five children and, like his two brothers and two sisters, attended Naperville Central High School. As a big kid, he played football and wrestled, competing in the 180-pound weight class. He excelled in both sports, participating for all four years of high school. He also did well in his studies and was inducted into the National Honor Society prior to graduation.

Mark graduated from high school in June 1963. He enrolled in Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, in the fall. Duke proved not to be a good fit, so after completing eighteen months, he transferred to Aurora College to be closer to home. Still, he found it hard to focus on his studies, especially since he participated on the college’s wrestling team. After a year, officials at Aurora College determined he wasn’t making sufficient progress and notified the local draft board.

With the Vietnam War raging and the Army and Marines needing more and more young men to fill their ranks, the draft board took swift action. Soon, Mark received a draft notice instructing him to report to the induction center in Wheaton, Illinois, at 6:00 a.m. on August 25, 1966. Although the notice itself surprised Mark, he was excited because he thought it would give him the opportunity to go to Vietnam and serve his country.

Until the report date arrived, Mark worked for a concrete construction company. Then, on Thursday, August 25, he reported as directed to the induction site. The atmosphere was subdued as it was early in the morning, and no one wanted to be there. Mark took his place with the other draftees and the officials told them they needed six Marines. Mark thought about being a Marine, but before he could say anything, six others volunteered. That meant Mark and the remaining draftees were headed for the Army.

The officials at the Wheaton induction center administered the oath of service to all the draftees and then sent them on their way for initial training. Mark was sent to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, but after a week of waiting there, he and those with him were flown to Fort Lewis, Washington, to begin Basic Training. Before boarding the flight, they were weighed, causing Mark to wonder if there was something wrong with the airplane such that the crew had to be careful not to have too much weight onboard. Much to his relief, the plane arrived safely at McChord Air Force Base just outside of Tacoma, Washington.

Mark and the other draftees transferred by bus from McChord to Fort Lewis to commence Basic Training. Mark was tagged almost immediately for a leadership position, Trainee Platoon Sergeant, which he attributes to him being a big guy and in good shape. As Trainee Platoon Sergeant, Mark stood in front of his platoon’s formation and gave instructions regarding formation movements. He also assigned people to KP (“kitchen police”) when it was their turn. Finally, he had to eat last when the platoon went to chow to ensure all his men got to eat. More than once, this resulted in Mark stuffing his mouth full of food when the allotted time for the meal ended and the platoon had to leave the chow hall.

Overall, Mark found Basic Training tolerable. Fort Lewis itself was beautiful, especially with Mount Rainier visible in the distance. Even the weather cooperated while he was there, with the only rainy period unfortunately coinciding with the platoon’s week in the field. No one complained, though, because everyone was in the same boat. Even the physical training proved not to be a problem given Mark’s wrestling experience and work as part of a concrete construction crew. He found rifle training more challenging, particularly because some trainees cut corners to get high scores. Mark was content to play it straight and accept whatever score he earned.

That marksmanship score, together with Mark’s other accomplishments, proved good enough for his platoon sergeant to nominate him for Soldier of the Cycle. Unfortunately, the platoon sergeant didn’t tell Mark about the nomination and only instructed him to report to a particular office at a particular time. Mark did as directed, wearing his usual training uniform. When he arrived, the other nominees were already there looking all spit and polished in their dress uniforms. Although Mark did not get the award, he considered it an honor to have been nominated.

Mark graduated from Basic Training in early November 1966. Pursuant to orders he received prior to graduation, he reported to Fort Sam Houston, located in San Antonio, Texas, for training to become an Army medic. Just as at Basic Training, the sergeants at Fort Sam Houston recognized Mark’s leadership potential and designated him as a squad leader. This gave him administrative responsibilities in addition to his medic training, which consisted of instruction on a wide range of medical skills. Mark learned how to triage illnesses and injuries, administer shots and medication, and even perform basic procedures like initiating an IV and administering an enema. Basically, Mark was trained as a first responder who had to be prepared to keep seriously wounded soldiers alive until they could be evacuated to a medical facility for further treatment by doctors and nurses.

Mark’s administrative responsibilities weren’t quite as daunting. On one occasion, Mark was directed to inform a soldier in another barracks he had KP duty. Mark found the soldier asleep in his bunk but couldn’t wake him up. He pulled the man to the floor; still the soldier did not wake up. Afraid something might be wrong, Mark alerted the soldier’s sergeant, who was not surprised. Together, they dragged the sleeping soldier by his hands and feet into the shower, where they woke him up by streaming cold water on him. On another occasion, the Army recognized Mark and the other soldiers designated as squad leaders with an evening out at a local brewery for a few beers. This was a memorable event for Mark, as he had very recently turned twenty-one. The next day, it was back to training as usual.

As Mark approached graduation from medic training, he was offered the opportunity to attend jump school to become airborne qualified. Because this would increase his monthly pay from around $125/month to around $180/month, Mark accepted the opportunity and transferred to Fort Benning, Georgia. He hoped it would lead to him being assigned to the 101st Airborne Division and sent to Vietnam so he could take part in the action. He arrived at Fort Benning in January 1967, where he learned to parachute from airplanes and operate as part of the Army’s highly mobile airborne forces. He also participated in rigorous physical training, including long runs, which he again excelled at given his history of physical fitness and involvement in sports.

After completing the three-week jump school at Fort Benning, Mark earned the right to wear parachutist wings on his uniform. However, instead of joining the 101st Airborne Division and heading to Vietnam as he had hoped, he received orders to report to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, for general medic duty. He was assigned to the 2nd Battalion, 325th Infantry, which was part of the 82nd Airborne Division. He lived in the barracks as did most of the other medics, with his sergeant telling them, “If the Army wanted you to have a wife, the Army would have issued you one.” Furthermore, what the Army expected of Mark at Fort Bragg was not very challenging. He served in a pool of medics where each morning, he was assigned to a unit requiring a medic for whatever training activities they were conducting that day. It was not the military experience Mark expected.

Sometimes Mark’s assignments took him out in the field with units on weeklong training exercises. During one such exercise, at about eleven a.m., a jet whizzed by low overhead, breaking the sound barrier and creating a massive sonic boom. The boom startled everyone, shaking everything nearby. The next day, the same thing happened, causing Mark to look over his shoulder every morning around 11:00 in expectation of another sonic boom ready to scare the daylights out of him. Every morning they came, just like clockwork, fraying Mark’s nerves.

On another occasion in the field, a soldier reported to Mark for sick call. Mark had three medications he could dispense, one in a green bottle, one in blue bottle, and one in a red bottle. By accident, he gave the soldier the wrong medication and the soldier spit it out declaring it tasted terrible. Mark then gave him the correct medicine and the soldier left. Mark was afraid the soldier might report him but he never did. Not surprisingly, the soldier never came back to sick call.

On one last occasion, a jeep drove by where Mark was working and he waved to the jeep’s passengers. Unfortunately, there was a colonel in the jeep who thought he deserved a salute from Mark rather than a wave. To help drive home the point, Mark was instructed to dig a large hole, which he did. After that, Mark didn’t wave at any more jeeps passing by.

When Mark had liberty, he enjoyed spending time in Fayetteville. On paydays, he and a friend met at an Italian restaurant for a nice dinner. On one payday when his friend couldn’t meet up with him, Mark went to a bar to grab a beer. There he saw an older gentleman with white hair, dressed in a sport coat and having a drink. The gentleman saw Mark, too, and started a conversation. He introduced himself as Tommy Bartlett, an entertainment celebrity who ran water skiing and skydiving shows in Wisconsin Dells, Wisconsin. Upon learning Mark was airborne qualified, Tommy told Mark if he ever visited Wisconsin Dells, he was welcome to jump out of planes there. This was Mark’s one brush with a celebrity during his hitch in the Army.

In the spring of 1967, Mark was unexpectedly transferred to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he joined Charlie Company of the 3rd Battalion, 187th Infantry, 101st Airborne Division. Even more unexpected, he and his unit were slated to go to Vietnam. And, due to a clerical error where someone mistakenly recorded his MOS (military occupational specialty) as 11B – infantryman rather than 91B – medic, he was issued an M16 and assigned duties as a rifleman rather than as a medic. The Army eventually caught the error and offered Mark the opportunity to revert to medic if he wanted, but since he had been training as an infantry soldier at Fort Campbell, he decided to stick with it. Accordingly, on December 4, 1967 – his sister’s twenty-first birthday – he and the rest of the 3rd Battalion boarded military transport planes and started the long journey to Vietnam dressed in their military fatigues and carrying their M16 rifles, ready for action. They made three stops along the way, the highlight being a 4:00 a.m. breakfast in Manila in the Republic of the Philippines. Then it was back on the planes until they arrived in Vietnam.

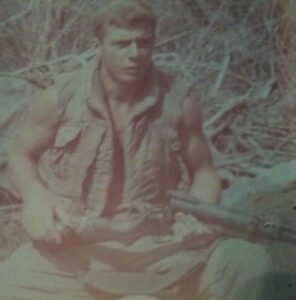

Once in South Vietnam, the 3rd Battalion deployed to its new base camp at Phước Vĩnh, located about forty-five miles northeast of Saigon. There they were joined by the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 506th Infantry, also part of the 101st Airborne Division. Once there, Mark’s first assignment was to fill sandbags and stack them around his barracks for protection from shrapnel and bullets in the event of an enemy attack. Then, after a short acclimation period, Mark’s platoon helicoptered to a landing zone where they were dropped off to patrol the surrounding area in search of Viet Cong. This turned out to be a typical mission, with Mark’s platoon or his company often being in the field up to two weeks before returning to the base camp to decompress and resupply.

Although Mark went on numerous patrols during his time in Vietnam, his platoon never engaged in a traditional firefight. Instead, Viet Cong guerrillas approached Mark’s unit under the cover of the jungle, fired at them, and then fled. As a result, Mark never knew when or where the enemy might be taking aim at him. Every step he took could be his last. Only once did he actually see a small group of Viet Cong firing at his platoon. They barely had the chance to return fire before the group disappeared. On another occasion the platoon came close, finding an abandoned Viet Cong camp with warm rice and tea right where the enemy left it before slipping away into the jungle. Faced with such hit and run tactics, Mark and the other members of his unit had to remain alert at all times – their lives depended on it.

The enemy wasn’t the only danger Mark had to be wary of. After securing a perimeter to bed down for the evening while out on patrol, Mark was standing next to a soldier armed with an M79 grenade launcher. Without warning, the soldier inadvertently fired the weapon, launching a grenade into the ground just inches from where Mark stood. Fortunately, the grenade had a safety feature that required it to rotate a certain number of times before it exploded, and it did not have time to reach that threshold before it stuck in the jungle floor. Had it gone off, Mark certainly would have been killed.

During another patrol where Mark’s platoon was acting as an ambush unit, a call went out for artillery support. The first round missed the target, so the forward observer gave correcting instructions. Someone somewhere made an error and the second round fell near Mark’s platoon leader and medic. Mark heard the artillery round screaming overhead and took cover just in time. He was covered by leaves from the blast. The man next to him wasn’t so lucky as he was hit by a piece of shrapnel and the platoon’s medic was killed. It was a horrible night Mark will never forget.

On another night nearer the end of his tour, Mark and three or four members of his squad went outside the perimeter of the base camp to set an ambush. Once in position, they each dug a fox hole for protection and then set their weapons out in front of them so they could easily access them in the event the enemy wandered into their trap. When a new soldier next to Mark set out his grenades, Mark noticed he had straightened the grenades’ safety pins making it possible for them to slip out, allowing the grenades to detonate. When Mark told him not to do that, the new soldier told him “Don’t tell me what to do.” The next day, the same new soldier had point and was carrying his M16 at his hip, parallel to the ground with a round chambered and the safety off. When he turned around, his weapon discharged, narrowly missing Mark and the soldier following behind him.

Despite these two clear safety violations, the patrol made it back to the base camp at Phước Vĩnh and resumed their normal duties. That night, while Mark and three others stood watch in a guard tower on the base perimeter, they heard an explosion in the vicinity of the barracks. They soon learned the explosion was not caused by an enemy mortar, but by an accidental detonation of one the grenades carried by the new soldier who had straightened the safety pins despite being told not to do so. Not only was that soldier killed, but another soldier in the barracks near where the new soldier was standing was also killed. It was a tragic incident that never should have happened.

Aside from the danger, going out on patrol was physically demanding. Mark’s rucksack weighed so much from the supplies he needed to carry to survive in the jungle for five or more days, he couldn’t pick it up and put it on. Instead, he set it on the ground and worked into it there, then had to try to stand up with it on his back. During one patrol in particularly hot weather, a tall soldier from California was overcome by the heat and had to be medevac’d by helicopter. Rather than send his rucksack back with him, the platoon sergeant asked for a volunteer to carry the pack with its extra supplies in case they might need them. Thinking if he carried the pack, he might be overcome by heat too and get to go back to the base camp, Mark volunteered. His plan didn’t work and he ended up carrying the rucksack for the remainder of the patrol.

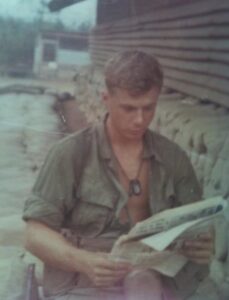

During patrols in Vietnam’s intense heat, water was more valuable than gold. Typically, Mark carried up to a gallon of water split between several canteens. This was usually enough to hold him until a helicopter could resupply the unit with water (and newspapers and candy) in the field, but sometimes the helicopters could not reach them in time. When that happened, they had to find another source of water. Once when the platoon ran out of water, Mark found a bomb crater filled with green and brown water so dirty he would not otherwise have gone near it. Now parched with thirst, he filled his canteen with the nasty water and added an iodine pill to purify it. He then had to wait twenty minutes to allow the pill to do its work. After seventeen minutes, Mark figured he’d waited long enough and drank the water, barely keeping it down. Fortunately, the pill did what it was supposed to and he did not get sick. Not much later, the resupply helicopter arrived with fresh water.

After a while, Mark developed a routine on patrol. In the evening, the platoon formed a circular defensive perimeter, with each man taking a position about ten meters from the next. Each man then dug a foxhole to bed down in for the evening. Mark always spread out his poncho in the fox hole first, then sat down on it with a hot cup of coffee, three cookies from his c-rations, and music from the Armed Forces radio station in Saigon. One night as he mellowed to the music in his own little world, a shot rang out and Mark instinctively dove for cover, crushing his cookies and spilling his coffee. For the rest of the evening, he had to fight off the bugs crawling into his fox hole trying to abscond with the cookie crumbs he could not get rid of in the dark.

Mosquitoes also posed a hazard because they carried malaria, but red fire ants were Mark’s true nemesis. Whenever shots rang out and he dove for cover, he often found himself popping back up because of painful fire ant bites. The ants were so numerous, sometimes the normally green leaves in trees a quarter of a mile away appeared reddish-green because they were crawling with so many ants. One time Mark caught a fire ant in some rubber tree sap and tried to kill it with a match. Instead of dying, the ant fought with the flame until it extinguished the fire, giving Mark all the more reason to fear the painful pest.

Leaches were another menace, particularly when Mark patrolled through rice paddies. Normally, everyone walked on the berms outlining the rice paddies, but sometimes they had to trudge through the water. Somehow, Mark avoided the leach scourge until his final patrol, when he was serving as point man on a mission through the jungle. When they stopped to take a break, he removed his boots and found a leach attached to his foot just above his big toe. He sprayed it with mosquito repellent and it fell off, providing yet another reason why he could not wait to leave Vietnam.

Sometimes patrols brought unexpected surprises. One day when Mark’s platoon was forging its way through tall elephant grass, they detected someone heading in their direction. Instinctively, they took cover and prepared to defend themselves. When the approaching group finally became visible, it turned out to be five or six bare-breasted Montagnard women carrying large jars of water on their heads. Without an ounce of fear, and despite seeing Mark and the other soldiers pointing weapons in their direction, the women carried on with their chore, smiling broadly as they walked by. The Montagnards were a fiercely independent indigenous people often allied with U.S. and South Vietnamese forces. Unfortunately, they were also extremely poor. When Mark’s platoon buried their empty c-ration cans and boxes in the jungle to keep them from giving away their position, Montagnard children living nearby often dug them up in search of something to eat or to shore up their ramshackle huts.

When Mark wasn’t patrolling in the field, he was back at the base camp in Phước Vĩnh. There he did lots of reading, wrote letters, and occasionally grabbed a beer at the enlisted man’s club. All the club’s empty beer bottles then had to be broken in two the next day using a trenching tool to prevent the Viet Cong from turning them into weapons like Molotov cocktails. Mark also had to stand duty guarding the base perimeter and perform latrine duty, which was particularly nasty. This involved taking the fifty-five-gallon drums filled with raw sewage from under the latrines and burning the contents with diesel fuel. The only bright side of the duty was it didn’t take long to get the fire started, so it gave him time to relax until the drums’ contents burned away.

Mark finally reached the end of his tour in Vietnam in August 1968. Although Army tours in Vietnam were normally one year, Mark was able to depart after just over eight months because his two-year service obligation was set to expire on August 25. In addition, while he was in Vietnam, he wrote Aurora College and asked if he could be re-admitted, which they approved. When the Army saw this, they scheduled Mark to be discharged two weeks early so he could begin the fall semester at Aurora College on time.

To put this plan into place, Mark departed Vietnam on August 8, 1968, returning safely to the United States in San Francisco. He was honorably discharged as a Specialist 4 (E-4) two days later, on August 10, giving him just enough time to return to Aurora College in Illinois to begin classes. This time, he had over $2000 in savings from his time in the Army and his GI Bill benefits to help offset the costs of attendance. He also returned part time to his cement contractor construction work, eventually partnering with a friend to start their own company.

In 1976, Mark attended a party his mother threw for an exchange student she was hosting from Japan. Across the living room, Mark saw a pretty girl, Linda Nease, standing in between her mother and father. He summoned up his courage and, with Linda’s mother and father listening to every word, he asked Linda if she would go out with him. Linda’s mother fully supported Mark’s request because she approved of Mark’s family. Linda’s father did not because Mark was twenty-nine and Linda was just nineteen. Linda’s father had the final word that night, but Mark did not give up. He called the director of nursing at the hospital where Linda worked and left a message asking for Linda to give him a call. She did and the two began to date.

Mark’s work commitments made earning his college degree difficult. In pursuit of needed academic flexibility, he enrolled in a number of programs, including at the Illinois Institute of Technology, the University of Illinois Chicago Circle Campus, and Control Data Institute, before he finally graduated from Aurora College with a bachelor’s degree in accounting in 1978. Two years later, an even more significant event occurred – he married Linda Nease. In 1994, they moved to Palm Harbor, Florida, after realizing the Sunshine State’s climate would be a better fit for Mark’s concrete construction business. They also started a home inspection business, with Mark conducting the inspections, although he occasionally employed other trained home inspectors to assist him. Linda ran the business, so she could be there for their growing daughter and son and all their activities and schooling. They finally retired in 2015 but still keep busy with their two children and six grandchildren, who all live nearby. Mark also continues to deal with the fallout from exposure to Agent Orange during his time in Vietnam.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Specialist 4 Mark Myers, U.S. Army, for his distinguished service during the Vietnam War. Drafted in 1966, Mark challenged himself as a medic, a paratrooper, and an infantryman, doing whatever it took to allow him to serve in Vietnam. Once there, he performed his duties under fire with courage and commitment, patrolling the jungles of Vietnam in search of a determined foe. For all he has done, and for the effects of the war he continues to endure, we thank him for his service and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Mark’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

February 21, 2024 @ 12:13 PM

Thank you so much for this post. My husband served in Vietnam and I did not ask a lot of questions about his experiences. Just thought that was best.

I would pay close attention to the conversations when he was with other Veterans. My appreciation for our Veterans continues to grow.

February 23, 2024 @ 9:14 AM

Pat – Thanks for taking the time to read Mark’s story and thanks for your husband’s service, as well.

February 21, 2024 @ 4:01 PM

Loved the story. I was in Cu Chi. I want to tell my story. Drafted right out of college so I was an old guy. Glad you made it back

February 23, 2024 @ 9:13 AM

Tom – Thanks for reading Mark’s story and thanks for your service, as well!

February 24, 2024 @ 8:08 PM

Very interesting recollections by Mark. He was lucky to have got back in one piece. Another fine write up Captain Grogan.

February 25, 2024 @ 8:27 AM

Carl – thanks for taking the time to read Mark’s story!

August 4, 2024 @ 7:21 PM

How interesting to read Mark Myers story having known his neighboring family many years ago, and to see how these “kids” look now in their retirement!

Featuring this fine man in this article gave me the lift of the day!

August 6, 2024 @ 11:37 AM

Jeanne – Thanks for reading Mark’s story – I’m so glad you enjoyed it!

V/r,

Dave Grogan

October 1, 2024 @ 11:42 AM

This was absolutely fascinating. Having known Mark for 0ver 20 years, it’s nice to see his story memorialized for everyone to enjoy.

October 14, 2024 @ 9:13 AM

Michael – Thanks for reading Mark’s story!