Sergeant Harold P. Jantz, U.S. Army – When Being Right Counts

Everyone understands soldiers follow orders. They must or their military organizations will devolve into chaos and fail. What makes the U.S. military unique, however, is it expects its soldiers to think and take the initiative, seizing opportunities that might otherwise be lost. Such was the case with Sergeant Harold P. Jantz, U.S. Army. When a far superior enemy force engaged his platoon during the Vietnam War, he charged into the fray and brought to bear the necessary firepower to defeat his foe. Without his quick thinking and forceful action, his entire platoon might have been destroyed. In the aftermath, he left no U.S. soldier behind. The events of that day were the defining moments of his life, molding him into the man he is today. This is his story.

Harold was born on Good Friday in April 1949 and spent his earliest years in North Merrick, a small town on Long Island, New York. He was one of six children and had four sisters and one brother. His father was a World War II veteran who served in the U.S. Army Air Corps in Italy, while his uncle “Doc” Jantz fought with the 82nd Airborne Division across northern Europe. After the war, Harold’s father and many of his relatives worked for the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation in Bethpage, providing his family with a solid middle-class income.

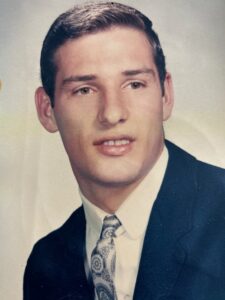

When Harold was seven, the family moved a short distance to Bellmore, Long Island, putting down permanent roots. Harold attended Bellmore Public Schools, including his first two years of high school at Wellington C. Mepham High School. However, when the new John F. Kennedy High School opened its doors in September 1966, Harold transferred there to complete his last two years. He was an outstanding athlete, having played baseball, football, and wrestling at Mepham, but he especially excelled at football. His football coach at John F. Kennedy High School immediately recognized his athletic ability and leadership skills and made him the team captain for both his junior and senior years. Harold reciprocated by fully committing to football and dropping the other two sports.

Football wasn’t his only love in high school. During his junior year, he met Valerie Dvorak, who was one year behind him, and they began to date. Their relationship was straight out of a high school storybook – the football captain dating the prettiest girl on the school’s “kickline team”. They dated all through high school and continued even after Harold graduated in June of 1968.

With his diploma now in hand, Harold followed in his father’s footsteps and started working at Grumman. Defense contractors like Grumman needed lots of workers to keep America’s fighting forces in Vietnam supplied. However, America’s need for soldiers trumped Grumman’s requirements, as Harold found out when he received his draft notice in early 1969.

On May 17, 1969, Harold reported for service as directed by his draft notice. He and the other draftees from his region traveled by bus to Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, New York, where they were sworn in as the newest members of the U.S. Army. They then boarded buses enroute to Newark International Airport, where they caught a flight to Columbia, South Carolina. When they arrived, they again boarded buses, this time headed for Fort Jackson and Basic Training.

Harold’s induction into the U.S. Army began in earnest at Fort Jackson. He joined a host of other draftees in an in-processing assembly line that continued for three days. At one point early on, he waited in line in his civilian clothes to enter a building. When he emerged from the building at the other end, he was wearing an Army uniform and carrying a duffle bag full of gear. His civilian clothes, and his civilian life, were things of the past.

After in-processing, the real Basic Training began. Harold and his fellow draftees moved to worn out, beat up, World War II era barracks in an area known as “the hill”. They trained there during May, June, and part of July, baking in the South Carolina sun. Harold was assigned to Company C62, led by Sergeant Citron from Panama who, despite being only about 5’2”, was “tough as nails”. Word was he’d had two tours in Vietnam. If that wasn’t enough, he was also the Army’s lightweight boxing champion. He made it clear no one should mess with him and no one did because everyone was afraid of him. He also told them they were going to Vietnam, and he was going to make sure they were ready.

Sergeant Citron made good on his promise. Sometimes he would wake up Harold’s company in the middle of the night and have them “low crawl” under the nasty vermin and spider-infested area under the barracks. He drilled into them they had to be prepared for anything and that they could not afford to hesitate because doing so might cost them their lives. He also assigned the men KP (“kitchen police”) to teach them to follow orders, but for Harold, he reserved an especially monotonous task – cleaning weapons in the armory, day in and day out. Surprisingly, Harold appreciated the assignment. He became an expert in disassembling, cleaning, and reassembling the M16 and other weapons like the M60 machine gun. He learned which parts failed frequently and what spare parts he needed to carry to repair his weapon in the field. A year later, Harold wrote Sergeant Citron, thanking him. He told him his experience in the armory really helped prepare him for combat in Vietnam.

Overall, Harold had a positive experience at Basic Training. Having been an excellent athlete in high school, he adapted well to the physical training. He also enjoyed meeting and working with the other draftees, who came from all walks of life and all regions of the United States. His company bonded well together, helping each other get through the ordeal.

Harold graduated from Basic Training in July 1969, but his training at Fort Jackson wasn’t over. His next stop was Advanced Infantry Training (AIT). There he became proficient with the M16 rifle, the M60 and .50 caliber machine guns, and hand grenades, and learned how to operate as part of an infantry unit in the field. He also moved into a newer and more comfortable barracks than the one he lived in during Basic Training, but his instructors still enforced strict discipline. Harold and everyone else knew their next assignment was Vietnam, so they took their training seriously. Their lives literally depended on it.

Harold completed AIT in early September 1969 and returned home to Bellmore on thirty days leave. To keep his mother from worrying, he told her the Army was sending him to Germany, a very believable scenario given U.S. commitments to NATO and the ongoing Cold War with the Soviet Union. His father wasn’t fooled. He knew Harold was going to Vietnam. He played along anyway, allowing Harold to have an enjoyable visit.

Harold said goodbye to his family and flew to Oakland Army Base in Oakland, California, on October 4, 1969. There he exchanged all his existing gear for new jungle gear, which he packed in his duffel bag for his flight to Vietnam. When his name was called, he took a bus to Travis Air Force Base, then boarded a charter flight to Japan. He changed planes in Japan and flew to the U.S. Air Base at Bien Hoa, located about sixteen miles northeast of Saigon, arriving on October 6, 1969. His tour in Vietnam had officially begun.

As if being sent halfway around the world to fight in a war wasn’t stressful enough for a twenty-year-old, Harold and most of the other young men on the plane had to do it alone. That is, they weren’t part of a unit that had trained together, bonded together, and then deployed to the war together. Instead, they were replacement soldiers, filling in at a unit for someone who had either gone home at the end of their one-year tour of duty or who had been wounded or killed in action. So, as Harold disembarked the plane at Bien Hoa, he had no idea where he was going or what he would be doing. He simply went where he was told and hoped he would fit in.

Along with the other newly arriving replacement soldiers, Harold boarded a “deuce-and-a-half” truck for the four-and-a-half-mile trip to Long Binh, the Army’s largest installation in South Vietnam. He checked in with the 90th Replacement Battalion, which would tell him where he would be assigned. That meant waiting a couple of days until they called his name and announced his assignment. When he finally heard his name, he learned he’d been assigned to the 199th Infantry Brigade (Light), known as the “Redcatchers” because their primary mission was finding and destroying Communist forces in Vietnam.

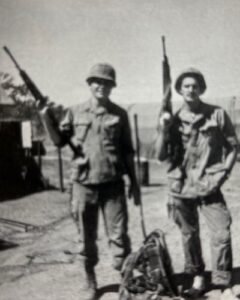

Harold reported to the 199th’s headquarters unit at Long Binh for in-processing. There he had to turn in all the jungle gear issued to him at Oakland Army Base. In return, he received yet another set of jungle gear. At the end of about three days, just long enough for Harold to start to acclimate to the weather, the 199th issued him his M16, his allotment of ammunition, and a knapsack filled with field supplies. They then put him in a helicopter to Fire Base Mace, located at the foot of Signal Mountain, about forty miles east of Saigon in an area permeated by North Vietnamese and Viet Cong activity. Signal Mountain was so named because of the important U.S. communications facilities at the top, making it the target of frequent enemy attacks. Part of the mission of the forces occupying Fire Base Mace was to make sure those enemy attacks never succeeded.

Once at Fire Base Mace, Harold learned he would be joining the 1st platoon of Bravo Company, 3rd Battalion, 7th Infantry, of the 199th Infantry Brigade (Light), which was currently conducting operations in the field. Armed and ready, Harold boarded a helicopter, which ferried him to a landing zone (LZ) in the jungle. To his surprise, his new platoon was engaged in a firefight, which he was now expected to jump into after only a few days in country and having never even met anyone he would be fighting alongside. He felt sheer terror as he disembarked the helicopter and joined in the engagement. Once he survived that experience, fear completely left him. For the rest of his time in Vietnam, he was afraid of nothing, because in his mind, nothing could ever be as terrifying as his first encounter with enemy fire.

After the firefight, Harold got to meet the men in his unit. His lieutenant, Roger Soiset, was from Georgia and a graduate of The Citadel, a prestigious military academy in South Carolina. As the lieutenant had a thick Georgia accent which was hard to understand on the radio, and as Harold had an equally thick New York accent that was easier to understand, Lieutenant Soiset immediately designated him his new radio telephone operator, or “RTO”. This meant in addition to carrying his weapon and his personal gear, Harold had to carry a twenty-five-pound radio on his back together with a supply of batteries. It also made him a priority target for the enemy because if they could kill a unit’s RTO, they could more easily isolate and destroy the unit. When Harold said he had no idea how to operate the radio, the lieutenant replied, “You’ll learn.” From that point on, Harold was the RTO for the platoon’s first squad, while Private First Class Lynwood Thornton served as the RTO for the platoon’s second squad.

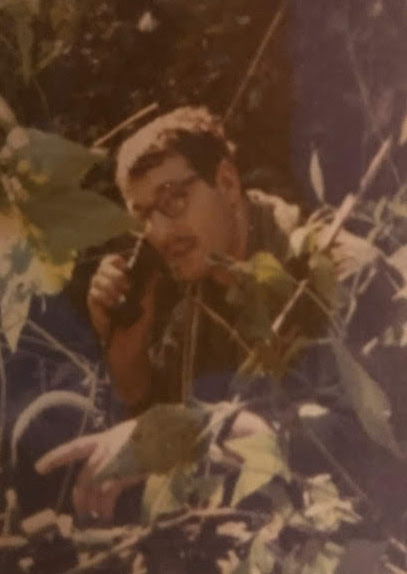

For the first three months of Harold’s assignment, his platoon operated out of Fire Base Mace. Their primary responsibility was to patrol in the vicinity of the Fire Base to locate and destroy enemy forces. Patrols lasted anywhere from three to ten days, depending upon the specific mission. Since a patrol involved the platoon trekking through the jungle on its own, the men had to carry everything they needed with them, including food, water, and ammunition. As there was no way they could carry enough supplies for the longer patrols, helicopters had to resupply them at designated LZs. If no LZ was readily accessible, the choppers dropped the supplies in the platoon’s vicinity, hoping enemy soldiers wouldn’t find them first.

During the dry months, water in particular, was a problem, because the streambeds ran dry, robbing the platoon of a ready source of drinking water. The solution involved helicopters dropping plastic mortar tubes filled with water to the thirsty soldiers. In contrast, during the monsoon season, water was not the issue – staying dry was. At times Harold stayed so wet his clothes literally started to rot off his back.

Eating in the field posed its own challenges. Harold and the others in his platoon packed and ate “C” rations while on patrol, which were canned foods that could be eaten hot or cold right out of the can. Harold took a photo of the label of one of the cans he was issued. It indicated it was canned it 1943, over twenty-five years before! Harold also sent a box top dated 1943 to his father, who was in the Army-Air Corps at the time, and told him he had forgotten to eat one.

When Harold wanted to heat his food or heat water for a cup of coffee, he didn’t use a Sterno can because those were just additional things he would need to carry. Instead, he rolled a small bead of C4 plastic explosive, which when lit burned with a hot blue flame. The trick was not to step on it to put out the flame, because it would blow up and cause serious injury. It simply had to burn itself out.

Navigating through the jungle also proved a challenge, especially when the thick undergrowth made it impossible for the platoon members to see more than a few feet in any direction. Making matters more difficult, the only tools for navigation were compasses and maps, and a skilled point man who could count steps and keep the platoon headed in the right direction. Periodically, Harold called over the radio for a white phosphorous round, known as “Willie Pete”, to be fired at a known location so the platoon could confirm where it was. Sometimes even this proved difficult because radio signals had to be sent line of sight, which meant bouncing the signal off an Australian Cessna “Bird Dog” aircraft circling in the vicinity or climbing a tree with the radio to send and receive a signal.

When the platoon identified where it would bed down for the evening, it had to ready its position in case of attack. This meant setting Claymore mines on nearby trails to prevent the Viet Cong from sneaking up on their camp at night, although sometimes they were roused by monkeys setting off the Claymore mines along the trail. Bravo Company headquarters also conducted hourly radio checks throughout the night to make sure the platoon was okay. Every hour, the call came over the radio, “Bravo Company, radio check.” Harold responded by clicking the microphone three times to signal all was well. He never responded verbally because doing so might give his position away if enemy forces were nearby.

To sleep at night in the jungle during the monsoon season, Harold and the other members of his platoon slung hammocks about a foot off the ground. That was just high enough to let the jungle’s snakes slither below them rather on the top of them. To stay dry, they covered themselves with their ponchos. Although this worked well, they still had to contend with giant centipedes and spiders with bodies the size of a closed fist. And while the snakes usually passed under the sleeping soldiers, if one did bite, they could prove deadly.

Sleeping wasn’t the only time Harold’s platoon had to contend with pests. After wading through rice paddies or streams, they often had to burn blood-sucking leaches off their bodies. And, after patrolling through the jungle’s underbrush, they had to check themselves carefully for ticks. On one occasion, they even heard tigers tracking them for several days.

After completing a patrol, the platoon returned to Fire Base Mace for a hot meal, a shower, a change of clothes, and a good night’s sleep. Then after a couple of days rest, and perhaps even a beer, the platoon would gear up and start on another patrol. It was a never-ending cycle.

On January 16, 1970, Harold’s platoon set out on another such patrol, this time in the Long Khanh Province, located about fifty miles northeast of Saigon. The platoon patrolled all day without incident. The next morning, a new lieutenant flew in by helicopter to join the platoon. He divided the platoon, sending one squad led by a sergeant in one direction, while he led the other squad in another direction. His intention was to search for the enemy in a cloverleaf pattern. Before Harold had walked 100 yards, firing erupted from the direction of the lieutenant’s squad. Harold, who was in the squad led by the sergeant, immediately tried to raise his counterpart, Private First Class Lynwood Thornton, on the radio, but received no response. He also did not hear the other squad’s M60 machine gun firing, so he knew there had to be trouble.

Acting on instinct, Harold grabbed the platoon’s medic, Richard “Doc” Uhler, and ran with him toward the firing. As they ran, they could hear bullets whizzing by their heads amid the roar of other gunfire. Harold returned fire with his M16, while Doc ran with him toward the lieutenant’s squad. After crossing a dry creek bed, they found the other squad engaging a vastly superior enemy force defending a base camp and hospital complex. They could see Lynwood was dead and that the M60 machine gun operator, Private First Class James Thonen, was gravely wounded. Doc set about rendering aid to Private Thonen while Harold took to his radio to summon help.

Harold’s first call was for a medevac helicopter to transport Private Thonen to safety. The helicopter arrived quickly, but with no LZ available and a major firefight in progress, its only option was to extract Private Thonen using a jungle penetrator to hoist him to safety. As he was too badly wounded to make the trip by himself, his best friend, Private First Class Jim Lunde, went with him into the chopper. Private Thonen died in his friend’s arms once they made it onboard.

Back on the ground, Harold called for fire support. He asked for “the world”, which meant all available artillery and aircraft should pummel the enemy position. Soon thereafter, high explosive shells rained down on the enemy, while both the platoon’s squads continued to fire. Battered by the overwhelming U.S. firepower, the enemy retreated, leaving Harold’s platoon to regroup and return to base. Before doing so, the Bravo Company commander radioed Harold and told the platoon to head to the LZ. When Harold told him they had one soldier killed in action, the company commander told him to leave the body there and get the rest of the platoon to safety. They would go back and get the body later.

Recognizing the enemy had retreated and they were now relatively safe, Harold had no intention of leaving Private Thornton’s body behind. Not wanting to get the other members of the platoon in trouble for violating the company commander’s order, he picked up Lynwood’s body and began to carry it toward the LZ. When the other men asked what he was doing, he told them the situation. All agreed they needed to take Lynwood back and they fashioned a stretcher from bamboo poles and their ponchos. They then carried Lynwood to the LZ four kilometers away, where they were extracted by helicopter and returned to the base camp.

Once back at the base camp, the Bravo Company commander berated Harold for disobeying his direct order. He told Harold he gave that order to prevent the platoon from suffering any further casualties in an uncertain and fluid situation. Harold replied he was certain the engagement was over and that they could bring Lynwood’s body back safely, as they had. He added, “if it was your body out there, wouldn’t you want us to bring you back for your family?” The discussion ended.

In March 1970, Harold’s platoon operated closer to home out of Fire Base Mace. During this time, the North Vietnamese started to climb the back side of Signal Mountain, hoping to overrun the U.S. communications facility at the top. Harold’s platoon was part of the Army’s response, maneuvering around the mountain to stop the North Vietnamese before they reached the top. After searching for two days, they spotted North Vietnamese soldiers in the jungle ahead and took them under fire. Harold then called for artillery support at “plus 100”, which meant the artillery should direct its firepower at a location 100 yards in front of Harold’s platoon.

For some reason, the artillery fired at Harold’s position, rather than the “plus 100” as requested. Three men in the platoon were wounded, one seriously. Harold called for a medevac flight, but none were immediately available. The commander of the 199th Infantry Brigade (Light), General William R. Bond, apparently overheard the request and dispatched his personal helicopter, which was brand new, to pick up the wounded soldiers. However, when the helicopter landed and the pilot saw all the blood, he said he could not transport the wounded because this was the general’s new helicopter.

When Harold heard this, he walked to where the pilot was sitting and brandished his M16. He told the pilot, “You’ve got no choice. You are taking these men.” The pilot looked at Harold and said, “Your serious, aren’t you?” He then allowed the wounded men to be loaded and flew them to safety. Shortly thereafter, General Bond was killed by a sniper’s bullet while inspecting troops in the field about seventy miles northeast of Saigon. He was the fifth general officer killed in action during the Vietnam War, and the first and only commander of the 199th Infantry Brigade (Light) to die from enemy fire.

Around April 1970, Harold’s assignment changed from platoon RTO to company RTO, where he worked as the RTO for the Bravo Company commander. At that point, the company moved from Fire Base Mace to another fire base in the mountains. Then, in late April, Harold joined elements of the 199th Infantry Brigade (Light) as part of an incursion into Cambodia to stop the flow of enemy supplies down the Ho Chi Minh Trail. He later wrote his father and said he was in Cambodia, to which is father replied, “the news says there are no U.S. forces in Cambodia”. Not long thereafter the news changed, acknowledging U.S. forces had fought in Cambodia, and that the 199th Infantry Brigade (Light) was among them.

After Cambodia, Harold’s company passed through Fire Base Nancy, located in the Quang Tri Province in the far north of South Vietnam, just west of the city of Hue. By coincidence, Harold had a friend from Wellington C. Mepham High School, Pete Kuchar, who was assigned there, so he started to ask around to see if they could meet up. As luck would have it, Pete had left shortly before and would not be back before Harold had to depart. They would see each other again, though, as Pete ended up marrying Harold’s sister.

After Cambodia, Harold continued to progress, becoming the RTO for the 3rd Battalion Commander, Lieutenant Colonel Bibb A. Underwood. He stayed in this position until near the end of his tour of duty in Vietnam. With two weeks left to go, he transferred back to Long Binh to await his flight. He also promoted to sergeant (E-5), just in time for his return to the United States.

Finally, after surviving a year of combat, Harold departed Vietnam on October 5, 1970, on a flight out of Bien Hoa Air Base. The North Vietnamese weren’t finished with him yet, though, as the plane was apparently hit during takeoff and had to make an emergency landing in Guam. After six hours in Guam, the plane took off again only to make another emergency landing in Alaska, where they waited for another twelve hours and a new plane to complete the final leg of the journey. They finally arrived safely at Travis Air Force Base and were transported by bus to Oakland Army Base for processing. Harold’s tour in Vietnam was officially over.

Once at Oakland Army Base, Harold was issued his Army dress green uniform adorned with his new sergeant stripes. He also received his ceremonial steak dinner for having survived his tour but jokes it very well may have been horse meat rather than steak. Whatever it was, it tasted better than anything he’d eaten in Vietnam. After completing his processing, he boarded a commercial flight in San Francisco and flew to New York’s JFK International Airport, where his high school sweetheart, Valerie, waited for him. He was finally home.

The town of Bellmore welcomed Harold with open arms. Every house on his street flew the American flag in recognition of his safe return. No one, however, asked him about his experience. In fact, his father had warned his siblings not to ask about it, so they never did. As a result, Harold never talked about it and tried to put his experience behind him.

Before he could do that, he had to finish his obligated service to the Army. Because he had more than ninety days left on his two-year commitment, the Army sent him to Fort Meade, Maryland, along with thousands of other soldiers who had served in Vietnam, to serve out their remaining time. As a sergeant, Harold had to stand duty at night, dealing with soldiers who’d gotten themselves into trouble. Recognizing they had just returned from Vietnam, he just made sure they got back to their barracks safely. He wasn’t about to cause problems for anyone who had just been through what he’d been through.

In March 1971, Harold came within ninety days of the end of his obligated service and qualified for an early discharge. With his honorable discharge in hand, he used his GI Bill benefits to enroll at Long Island Tech and pursued a two-year degree in architectural engineering. A professor at the school helped him get a job at a millwork shop, where he became a millwork draftsman. Over time, he honed his skills in construction, working as an independent millwork contractor, starting with small office buildings and eventually working his way into high rise contracts for buildings in Manhattan. He always prided himself in getting jobs done on time and on budget.

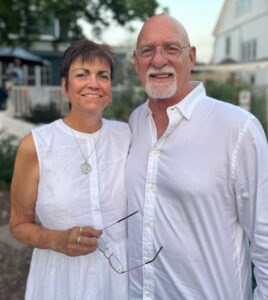

As for his personal life, Harold married Valerie in 1973. They have three sons, and so far, six grandchildren. Harold attributes his survival after the Vietnam War directly to his family, but especially to Valerie, who stuck with him and helped him get through some difficult times. Despite trying hard to bury his Vietnam experience, he lived with it every day, and continues to do so today. However, in 2019, an event happened that helped bring some peace to Harold, so many years after his experiences in Vietnam.

On July 10, 2019, Senator Lindsey Graham presented Harold with the Bronze Star with “V” for valor for his heroic actions on January 17, 1970. The award had been approved by the Secretary of the Army in May, forty-nine years after the events giving rise to the award transpired. In addition, the Secretary of the Army also approved the Bronze Star posthumously for Private First Class Lynwood Thornton. Lynwood’s award was presented to his family in Thomasville, Georgia, and Harold, Lieutenant Soiset, Doc Uhler, and Robert Kenney, attended the ceremony. There they were able to answer many questions Lynwood’s family had about his death, bringing a degree closure for everyone.

Now fully retired, Harold and Valerie enjoy spending time with their family and friends, but especially their grandchildren. Harold also remains active in American Legion Post 269 and VFW Post 2913, both in Patchogue, New York. And he continues to get together with Lieutenant Roger Soiset, Doc Uhler, Robert Kenney, and other members from Bravo Company of the 199th Infantry Brigade (Light), as they work through the events that took place all those years ago.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Sergeant Harold P. Jantz, U.S. Army, for his service during the Vietnam War and his bravery under fire. He rose to the occasion when his platoon needed him most, calling in fire support that likely saved everyone’s lives. He then ensured his fallen brother was not left behind. All we can do is thank him for upholding the honor of those who serve in the U.S. military and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Harold’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.