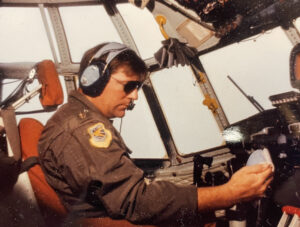

Major Sandy Richardson, U.S. Air Force (Retired) – From Dream to Reality, Flying with the Air Force for 20 Years

Some people dream and that is as far as it goes. Others follow through and take action, always keeping their eyes on the ultimate objective. Ever since Major Sandy Richardson, U.S. Air Force, was a boy with his father watching planes take off and land in Louisiana, he dreamed of becoming a pilot. Now he can look back at his fifty-year career of flying and training others to fly and say with pride, “I lived my dream.” This is his story.

Sandy was born in Shreveport, Louisiana, on July 18, 1948. His father was an administrator/tower controller with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and his mother was a schoolteacher. When Sandy was in the fifth grade, his parents moved their family to Lafayette, then a city of about 40,000 people, located in south central Louisiana. With the oil and gas industry booming off Louisiana’s coast and the aircraft flying in support of the boom filling the skies, the FAA needed Sandy’s father in Lafayette to help control the situation and make sure the airspace was managed in a safe and efficient manner.

Needless to say, Sandy’s father spent a lot of time at airports and Sandy often went with him. As Sandy watched the planes take off and land, he dreamed of one day becoming a pilot. As he sat in the living room of his family’s home, he put on his father’s leather flying helmet and pretended to talk to the planes on a microphone as he watched every episode of the popular 1950s TV show Sky King, which featured an Arizona rancher using his Cessna airplane, Songbird, to track down criminals and rescue wayward hikers. Sandy’s desire to fly only grew stronger as he got older.

Sandy attended Lafayette Senior High School, where he played baseball for a while, but didn’t continue because he was physically too small. He started working at the local A&P grocery store when he was fifteen, bagging groceries, stocking shelves, and doing whatever else he was told to do. He graduated from high school in May 1966 at the height of the Vietnam War draft. Over 380,000 young men would be drafted that year to fight in the jungles of far-off Vietnam.

The draft was not an immediate concern for Sandy just yet. His grandfather, Edwin S. Richardson, had been president of Louisiana Tech University from 1936 to 1941, and his father, mother, and older sister were all alumni. Given that legacy, Sandy’s future was pre-ordained. He enrolled at Louisiana Tech, located in northern Louisiana about seventy miles east of Shreveport. Despite his family’s history there, the school was not for him and he barely managed to finish his freshman year. He then had a hard conversation with his parents, telling them the University of Southwest Louisiana in Lafayette would be a better fit.

With his parents’ blessing, Sandy enrolled at the University of Southwest Louisiana in the fall of 1967. He was determined to remain in good academic standing because he’d seen some of his friends fail out and get drafted for the ground war in Vietnam. He majored in business and kept up with his studies, but what he really wanted to do was fly. Knowing that, Sandy’s father invited a friend who was a pilot for Eastern Airlines to the house to talk to Sandy. The friend told Sandy, “If you want to fly, you need to get into military aviation. They have a great program and will teach you the right way.”

Sandy took the advice to heart and went to a career fair during his senior year, where he spoke to a Navy recruiter. The recruiter told him about the Navy’s Aviation Reserve Officer Candidate (AVROC) program, which would allow him to complete his bachelor’s degree before reporting for officer training and flight school. Sandy was sold and signed up for the program. About six months before graduation, the Navy invited him and other AVROC participants to New Orleans to be sworn in as officer candidates. Before the swearing in ceremony, they were flown to Pensacola, Florida, to spend a day and a night at sea on the training aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CVT-16), an Essex-class aircraft carrier that saw action throughout the Pacific theater during World War II. Once the ship was at sea, Sandy and the other candidates watched new Navy pilots practice takeoffs and landings on the carrier’s flight deck. At night they slept aboard the ship, getting a taste of what life at sea was like.

The experience changed Sandy’s career trajectory – he hated the shipboard experience. So much so, that when the group returned to New Orleans to be sworn into the Navy, Sandy refused to raise his right hand and take the oath. Much to the Navy’s chagrin, especially since he’d already passed his physical and all the required tests, he told the Navy he was no longer interested and returned to the University of Southwest Louisiana a civilian.

After graduating from the University of Southwest Louisiana with a business degree in May 1971, Sandy’s next stop was with an Air Force recruiter. The recruiter was more than happy to work with him, especially knowing he’d previously qualified for the Navy’s flight program. Again, he passed the physical and all the required tests, but the Technical Sergeant (E-6) guiding him through the recruiting process gave him the runaround. Although he had promised Sandy the pilot program, he said he couldn’t guarantee a pilot slot. He suggested instead taking a navigator slot and then once in, doing a lateral move to the pilot program. Then he said he couldn’t guarantee the navigator slot either and Sandy should enlist and go to boot camp in order to open the door to the pilot program. Sandy was unwilling to gamble on his future and decided to wait until he could be guaranteed a pilot slot.

One afternoon, Sandy was drinking beer with a neighbor from across the street whom he knew to be a Marine Corps pilot. Sandy told him the problems he was having and the Marine told Sandy he’d go with him to the recruiter on Monday morning to take care of it. Much to Sandy’s surprise, the Marine showed up on Monday morning in a general’s uniform! Even more surprised was the Air Force Technical Sergeant when the general came into the recruiting office and asked to see his captain. Miraculously, all the problems disappeared and Sandy was given a pilot slot and sworn into the Air Force by 3:00 the same day. His flying career had finally begun.

Sandy packed his car and drove to Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas, for Officer Training School (OTS), which began on November 3, 1971. He did not find the ninety-day school, which taught the basics of being a new officer, very challenging. As long as he and his fellow trainees could run, salute, and make their beds, they did fine. There was even a class on how to eat properly, which Sandy had no problem with because his mother had been a stickler with him on table manners. Still, not everyone made it to graduation, which was merely a steppingstone to the next truly challenging level – pilot training.

Now an Air Force second lieutenant with ninety-days of experience under his belt, Sandy reported to Columbus Air Force Base in Columbus, Mississippi, for pilot training in February 1972. Because his class was not scheduled to begin for several months, he was placed on “casual status” and put in charge of the T-37 flight simulators (the T-37 was a Cessna twin-engine jet and the primary trainer for the Air Force at the time). He was also sent to Fairchild Air Force Base in Spokane, Washington, for Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape training, or SERE School. Normally, only officers who had completed flight school attended the intense two-week training, which teaches air crew how to survive and evade capture after bailing out of their aircraft over enemy territory. Since Sandy had not attended pilot training yet, he was unaware of the grueling physical and mental trials he was about to undergo. Still, he made it through SERE School and, on the positive side, did not have to complete it again after he earned his pilot’s wings.

Sandy and about fifty classmates finally began their fifty-four weeks of pilot training on July 17, 1972. In addition to hours of classroom instruction and physical fitness, Sandy and the other trainees got their first taste of the cockpit at the local airport in the T-41 Mescalero, the Air Force’s version of the Cessna 172. They spent about ten hours in the T-41, which the Air Force used to assess their basic flying aptitude. From there, Sandy transitioned to the T-37 and eventually to the T-38 Talon, a supersonic two-seat trainer still used by the Air Force today to train its pilots. Sandy loved the T-38 and found flying it exhilarating.

Flight training was, and was intended to be, stressful. Day one began with the instructors screaming, ranting, and raving at the trainees, warning them the man sitting next to them would not be there in six months – and they were right. Of the fifty trainees that started with Sandy, only twenty-six graduated. When a trainee failed on a flight, they were given another chance on what was known as an “87 ride”. If they failed the “87 ride”, they were given another chance on an “88 ride”. If they failed the “88 ride”, they were given one final chance on a “wash out ride”. If they failed, they were dropped from pilot training and sent to Navigator School. For that reason, the trainees jokingly referred to pilot training as “navigator prep school.” One officer in Sandy’s pilot class washed out just two-weeks before graduation.

As graduation neared, the training Wing Commander asked the trainees if any distinguished visitors (DVs) would attend graduation. Since Sandy only had his family attending, he didn’t think anything of the request, so he was surprised when the Wing Commander called him to his office. The Wing Commander asked why he did not tell the command his father was attending graduation. Sandy said it was just his father, but the Wing Commander told him his father was a GS-15 with the FAA and assured him that meant he was a DV. Sandy said he understood and left the office, a little more impressed with his father’s position.

The prospective pilots needed 210 flying hours to graduate from flight training. With the graduation ceremony drawing near, Sandy needed one more flight to get over the limit. As he was flying around the area, his T-38 lost one of its two jet engines, which was not a big deal because it was something Sandy had been well-trained to handle. He radioed in the emergency and started to return to the airfield to land. Unbeknownst to him, his father and mother had been given access to the Runway Surveillance Unit (RSU) to watch the day’s flight operations. They heard the emergency called in and were stunned to learn the pilot of the plane with the emergency was their son. Sandy’s mother nearly had a heart attack, but Sandy landed the plane without incident and graduated from flight training on schedule, having achieved the required 210 flight hours. His mother pinned on his flight wings during the graduation ceremony.

New pilots like Sandy basically had two career options: flying fighters or flying bombers and tankers. Although Sandy was fighter qualified, there were only three fighter slots available, so that left bombers and tankers. With U.S. combat operations in the Vietnam War having just ended and the Cold War with the Soviet Union at its peak, the Strategic Air Command (SAC) desperately needed pilots. SAC operated the Air Force’s B-52s as part of the U.S. nuclear deterrent triad, the other two elements being land-based and submarine-launched ballistic missiles. In the past, few new flight school graduates wanted to fly B-52s, so SAC often got pilots from the bottom of the class. Now, with the emphasis on SAC’s mission, new pilots were being channeled to B-52s and Sandy was one of them.

After graduating from flight school in July 1973, Sandy drove 1,800 miles from Columbus, Mississippi, to Castle Air Force Base in Merced, California, to learn to fly B-52s. His training lasted 105 days and qualified him to fly in the right seat (copilot) of the big strategic bombers. He quickly learned to love flying the plane, but once he reported to his first command, he better understood why pilots were not enthralled with taking the bomber/tanker career path.

Sandy’s first assignment as a newly qualified B-52 pilot began in November 1973 with the 596th Bombardment Squadron at Barksdale Air Force Base in his home state of Louisiana. Before he could fly operational missions, he had to get nuclear qualified, which he did at Carswell Air Force Base in Fort Worth, Texas. He then began to serve as a copilot on the Alert B-52s, which provided strategic bombers armed with nuclear weapons ready to take off on a moment’s notice. Each airplane had a specific mission to fly, so the crews were trained and ready to go should they be called upon for action. To ensure they could launch quickly, the Alert B-52 crews, together with the tanker crews that would help the B-52s get to their targets by refueling them in flight, lived together in a facility they called the “Mole Hole” for their seven-day Alert assignment. The Alert planes were also dispersed to Air Force bases in Texas, Oklahoma, and Missouri, so a single incoming strike by missiles on Barksdale could not destroy them all at once.

Even the non-Alert B-52 missions were physically and mentally taxing. The day before flying an assigned mission, the flight crew spent six hours planning the flight. Then on execution day, the mission itself typically involved twelve to fourteen hours of flying. Sandy’s longest mission lasted twenty-six hours in the air. That said, the end of the Vietnam War brought many B-52 aircrew back to the United States and all of them needed cockpit time to stay current, so actual flight time in the B-52 became scarce. Sandy typically only flew one mission every forty-five days. The rest of the time he maintained his flying skills in the B-52 simulator. Then, the Air Force introduced a program where B-52 pilots could maintain their currency by flying T-37s, which were brought to Barksdale for that purpose. The pilots were permitted to fly the T-37s wherever they wanted, as long as they flew the required number of hours and made the necessary number of take offs and landings. Sandy took advantage of the opportunity and used the planes to fly to Lafayette to visit his parents and go hunting and fishing with his father.

At times, the operational requirements increased. Sandy did two 180-day rotations in Thailand flying missions in Southeast Asia. These assignments involved flying the B-52D model, and since Sandy was qualified on the later B-52G model, he had to go to Carswell Air Force Base to get certified on the B-52D before he could deploy. Sandy describes the Thailand missions as “peacekeeping” missions, keeping a watchful eye in the area after U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War ended.

Recognizing the SAC lifestyle and operational outlook weren’t what he was looking for, Sandy searched for other options. An opportunity arrived in the form of a letter asking for T-39 pilots. T-39 Sabreliners were basic seven-passenger jets serving as Operational Support Aircraft (OSA). Operationally, they were assigned to the Military Airlift Command with a mission of transporting VIPs wherever they needed to go. Sandy applied for the assignment and was accepted in September 1976; his B-52 flying days were over.

Sandy met all sorts of VIPs in his new role. Besides the normal mix of three and four-star generals, he flew the likes of Senator Barry Goldwater and other members of Congress around the United States. Most trips began or ended at Andrews Air Force Base in Washington, DC. Because the trips involved very senior U.S. government officials, they required a new diplomatic skillset. For example, when flying a three or four-star general, Sandy put a placard in the window with three or four red stars if the senior passenger was an Army general and three or four blue stars if the senior passenger was an Air Force general. On one of his earliest trips, when he went out to greet the arriving four-star Army general, the general asked him, “Captain, how do I look to you, today?” Knowing this could not be good, Sandy responded, “You look fine, sir.” The general continued, “Well, that’s not what the stars in your window say. You’ve got them upside down, which means you are transporting a deceased general.” Sandy did not make that mistake again.

When Sandy’s Barksdale tour officially ended in August 1977, he took a permanent assignment with the 58th Military Airlift Squadron at Ramstein Air Base in West Germany, again flying VIPs on T-39s. He was surprised, though, when he arrived at the commercial airport in Frankfurt to begin his assignment and no one was there to help him get to the base and checked into his new command. He made it to Ramstein on his own and reported to his new command only to learn his orders had been cancelled, so the command was not expecting him. Fortunately, the squadron commander stepped in and since Sandy was already in Germany, the Air Force relented and allowed him to stay.

With twenty-one general officers on Ramstein Air Base alone, Sandy got plenty of flying time. He also flew ambassadors, members of Congress, and other VIPs around Europe. Oftentimes, the VIPs would have unusual requests. For example, a Congressman visiting Spain was presented with a large rock. His staff told Sandy he needed to load it onto Sandy’s T-39. When Sandy responded the rock was too big to fit on the plane, a much larger C-130 “Hercules” transport plane was requisitioned to transport the rock for the Congressman.

On another occasion, Sandy was tasked with transporting a general with an impressive flying record, including having been commanding officer of the Air Force Thunderbirds and astronaut qualified. Their destination was Northolt, the Queen’s airfield, outside of London. The runway was short and slick when wet, which was particularly hazardous for the T-39 because it didn’t have anti-skid brakes or thrust reversers. The conditions were so bad, in fact, that Sandy needed to be specifically qualified to land there. On the flight to Northolt, the general sat in the pilot’s (left) seat and flew the airplane, but as they approached the field, Sandy said he would have to make the landing. The general disagreed and pointed to the four stars on his shoulders, asking Sandy why he thought he was a better pilot than the general. Sandy explained the hazardous conditions (it was raining at Northolt) and that he had the special qualifications needed to make the landing safely. It got so heated, Sandy actually had to hand the general the orders for the flight making it clear Sandy, as the aircraft commander, was in charge for the flight. The general angrily acquiesced, telling Sandy, “Captain, you won’t be here tomorrow.”

Once on the ground, Sandy called his squadron commander to tell him what happened. Two hours later, Sandy got a call directly from the four-star general in command of the entire Military Airlift Command. When Sandy explained what happened, the general told him to go to his airplane the next day as scheduled to pick up the angry four-star, and if he didn’t want to fly with Sandy, the four-star could walk to his destination. Sandy did as instructed but when the four-star arrived for the flight, instead of being angry, he apologized. Sandy had done the right thing and it paid off.

On June 25, 1979, Sandy was tasked with picking up General Alexander Haig, who at the time was the NATO Supreme Allied Commander Europe, at an airstrip in Belgium. As Sandy was waiting for the general to arrive, a column of black sedans barreled onto the airstrip and stopped at the plane. A staff member jumped out and told Sandy to get the plane in the air—NOW! He said they needed to go “wheels up” as soon as the general got onboard because one of the cars in the motorcade had just been blown up in an attempt to assassinate the general. Sandy did as instructed and flew General Haig to safety.

Missions to and from Berlin also proved stressful, because at the time Berlin was surrounded by communist East Germany. Sandy had to fly his unarmed jet through one of three narrow Allied air corridors leading from West Germany to Berlin. If he flew near the edge of the corridor, Soviet Mig fighter jets would fly close by to check him out. More than once, Sandy observed the Migs flying nearby, but there was never an incident because he always remained in the Allied corridor.

By far the most consequential event during Sandy’s tour at Ramstein was he met his future wife at the officer’s club one Friday night. Randi Habersang had just arrived at Ramstein two days before to take a secretarial job when she saw Sandy “float through the bar.” Although she thought he appeared cocky, they went out after being introduced by mutual friends.

When Sandy’s tour with the 58th Military Airlift Squadron came to an end in August 1979, the Air Force wanted him to return to flying B-52s out of Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota. The only other option offered involved flying C-130 “Hercules” transport planes out of Elmendorf Air Force Base in Anchorage, Alaska. Sandy jumped at the opportunity to fly C-130s. After taking time off to marry Randi on October 13, 1979, Sandy spent the rest of 1979 qualifying in the C-130 at Little Rock Air Force Base in Little Rock, Arkansas. Then he and Randi departed for Elmendorf Air Force Base to begin their Alaskan adventure.

Sandy reported to the 17th Tactical Airlift Squadron at Elmendorf in January 1980. The squadron’s primary mission was to keep the many remote military sites throughout Alaska resupplied. For many of these sites, airlift was the only way in and out. In fact, some of the landing zones at the sites were so treacherous, once Sandy committed to making a landing, pulling up and circling around wasn’t an option – he either had to land or crash.

A colonel from the Air Force Inspector General’s Office who had previously flown for the Thunderbirds learned that firsthand when he visited Elmendorf for an inspection. After spending the bulk of his time with the airbase’s fighter squadrons, he agreed to fly on a C-130 mission with the 17th Tactical Airlift Squadron to Sparrevohn. Sandy was the plane’s pilot. After Sandy did a spiral-down approach into a holding pattern for the first destination, the colonel started to become interested in the flying and stood on the flight deck behind Sandy’s shoulders. As they approached a landing zone on the slope of a hill with hydraulic fluid marking the center of the zone, Sandy called out “committed” and lowered the big plane’s flaps to land. The colonel asked Sandy if he did this often and when he said he did, the colonel replied, “You guys are crazy!” Once they made their other stops and returned to Elmendorf safely, the colonel invited the plane’s officers to the club and said, “I’m buying”.

On another occasion on a flight to Indian Mountain, Sandy noticed a bear on the landing zone. As he was already committed to land, his intention was to fly over the bear without hitting it, because a collision could prove deadly for both the bear and the plane and its crew. At the last minute, the bear decided to move off the landing zone and Sandy was able to put the plane down safely. As he taxied slowly to the end of the runway, he saw the rear door light illuminate, indicating the loadmaster was opening the ramp in anticipation of unloading the plane’s cargo. Then suddenly, the light went out indicating the door had closed. When Sandy asked what the problem was, he learned the bear had only temporarily taken refuge while the plane landed and now it was following the plane to its parking space. The huge grizzly walked all the way to the front of the plane and looked at Sandy before finally wandering off, allowing the ground crew to escape from the fire truck they had crammed into when the big bear approached.

Sandy and Randi consider their years in Alaska some of their best. Not only did they enjoy Alaska’s beauty, but their first son, Rich, was born there in 1981. By the end of 1983, though, it was time to transfer, and Sandy received orders to Travis Air Force Base in northern California where he would be assigned as the Chief of C-130 Flight Safety for the 22nd Air Force. Before reporting, he was sent on temporary duty to the University of Southern California to learn how to conduct mishap investigations. This meant he had to leave Randi, who was seven and a half months pregnant with their second child, and Rich behind in Anchorage. After completing the school, Sandy returned to Anchorage to accompany Randi and Rich to Travis in November 1983.

As the Chief of C-130 Flight Safety, now Major Sandy Richardson was responsible for all safety issues for every C-130 west of the Mississippi River. This meant he spent a lot of time on travel throughout the Pacific, working with squadrons and airplanes in Hawaii, the Philippines, and Japan. In fact, as soon as Sandy arrived at Travis, he was sent on travel for three-and-a-half weeks, making it back to Randi just in time for the birth of their second son, Shawn. Sandy’s other significant responsibility was to conduct investigations when C-130s suffered mishaps. To prevent bias, he was only assigned to investigations involving 21st Air Force C-130s, which were those located east of the Mississippi River and in Europe and Africa. The 21st Air Force reciprocated by investigating C-130 mishaps involving 22nd Air Force airplanes.

As Sandy approached the end of his four-year tour, he learned he was being considered for a one -year unaccompanied short tour in Bizerte, Tunisia, to work with Tunisian C-130 air crew to improve their flying skills. Sandy told his command he didn’t want to go and the command pushed back for him, but to no avail. As he was planning the 22nd Air Force staff going away party to recognize departing officers, it turned out unexpectedly to be for him and Randi. He had ninety days to report to Bizerte, Tunisia, and move and settle Randi and their sons to San Antonio, Texas.

After attending a crash course in Arabic, Sandy reported to Bizerte in October 1987 and found himself in charge as the senior U.S. Air Force officer on the ground. This meant not only was he responsible for training the Tunisians, but he also was responsible for evacuation plans for the U.S. military and contractor personnel there in case something went wrong. More relevant to his original tasking, he found Tunisia had only two C-130s in its Air Force and its pilots had limited skills. This meant he had to be on special alert whenever he flew with them, always ready to take the plane’s controls.

Sandy did get one opportunity to visit his family once during his Tunisian tour. The mission was to fly one of the Tunisian C-130s back to the United States, stopping at Andrews Air Force Base in Washington, DC, then on to Texas, back to Andrews, and finally returning to Bizerte. When it came time for the plane to depart Bizerte, Sandy could tell the plane was really overloaded. He asked the loadmaster what the plane’s weight was. The loadmaster replied 155,000 pounds, which was the plane’s maximum fully loaded weight. The loadmaster also said the weight was precisely balanced over the C-130’s wheels. When Sandy looked at the weight and balance form, he could see the form had been erased multiple times.

By just looking at the way the plane was sitting, Sandy knew the plane’s weight and balance weren’t accurate. He asked the loadmaster what was in the back of the plane and the loadmaster said it was classified. Sandy didn’t buy it. He looked in the cargo bay for himself and saw it was loaded with pallet upon pallet of twenty-four-inch by twenty-four-inch boxes filled with posters encouraging people to vacation in Tunisia. With that load in the cargo bay, Sandy estimated the plane’s weight had to be at least 190,000 pounds with full fuel. He told the Tunisian air crew the plane wasn’t leaving until the load was reduced to within specifications. After four days of wrangling that involved the U.S. embassy in Tunis, the excess cargo was finally unloaded and the plane took off enroute to the United States.

On the way into Washington, DC, the plane lost one of its four engines, so once it landed at Andrews, the trip couldn’t continue. The Tunisians had two options – they could wait for an engine to be shipped to Andrews for the necessary repairs, or Sandy could fly the plane on its remaining three engines to Kelly Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas, where it could be repaired and the Tunisians’ visit could get back on schedule. The Tunisian crew elected the latter option and Sandy flew the plane to Texas without incident. While the plane was being repaired, Sandy visited with Randi and their two boys, who were living in San Antonio. After the plane was repaired, Sandy said goodbye and made his way back to Tunisia to finish his tour.

Sandy returned to the United States permanently in October 1988. He was offered two assignments, either the Africa Desk at the Pentagon or as a C-130 instructor pilot at Little Rock Air Force Base. Sandy took the instructor pilot job and moved his family to Cabot, Arkansas, where he has lived ever since. He was initially an instructor pilot for the 16th Tactical Airlift Training Squadron, but soon transferred to the 62nd Tactical Airlift Squadron once he updated his tactical flying qualifications. There he trained not only U.S. C-130 pilots, but also C-130 pilots from around the world. He served as the chief instructor pilot with the 62nd Tactical Airlift Squadron until he retired from active duty on November 30, 1991.

As with many retiring military pilots, Sandy’s post-retirement plans were to fly for a major airline. But after discussing it with Randi, they agreed he’d been away from the family a lot and he should pursue a job that would allow him to be at home. His first thought was to see if there might be a position training C-130 pilots on the simulators at Little Rock Air Force Base. When he went to inquire about a position, he was hired on the spot and told to report for work the following Monday. He held that position for thirty years, finally retiring in October 2022. He and Randi are now enjoying retirement, with their two son’s families, including their three granddaughters, Landry, Anna, and Elle, living in Little Rock and Oklahoma City.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Major Sandy Richardson, U.S. Air Force (Retired), for his fifty years of service to our nation, including twenty years on active duty and thirty years as a flight simulator instructor training the next generation of C-130 pilots. From patrolling the skies as part of the U.S. strategic bomber force, to safely transporting military and civilian leaders around the U.S. and Europe, to flying hazardous C-130 missions around the globe, Sandy epitomized the Air Force’s fly, fight, and win motto. We thank him and his family for the many sacrifices they made during Sandy’s career and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Sandy’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.