Master Chief Petty Officer Donald Gohman, U.S. Navy (Retired) – Keeping the Navy Flying During Three Wars

Master Chief Petty Officer Donald Gohman, U.S. Navy (Retired), is a humble man. When we began to talk, he told me his career was routine and he didn’t think he’d done anything special. Then he told me about how he helped keep planes flying from Henderson Field during the six-month long battle for Guadalcanal during World War II and kept carrier aircraft in fighting shape for missions over Vietnam during the Vietnam War. Needless to say, I was spellbound. Weaving in and out of peacetime and war, Don’s career is a thirty-year American history lesson taught at the individual level. I could not get enough of it, and I think you will share the same view. This is his story.

Don was born in March 1924 and raised in Clear Lake, Minnesota. His parents owned a 240-acre farm, raising cattle, hogs, and poultry, and growing the grain to feed them. As Don was the only child, he learned to carry his weight on the farm at an early age. He drove his first team of horses when he was only five years old. He attended school in a one-room schoolhouse, progressing through the eighth grade. At that point, many children stopped attending school so they could work full time on their families’ farms. Don, however, asked his father if he could attend high school. Don’s father agreed, provided Don continued to do his work on the farm, which he did.

Getting to high school proved to be a challenge, especially in the harsh Minnesota winters. When the roads weren’t covered with snow and ice, Don rode his bike the three-and-a-half miles to St. Cloud Technical High School. When he couldn’t ride his bike, he rode a horse. On one particularly cold morning when the thermometer registered thirty-two degrees below zero, Don asked his dad if he had to go to school. His dad simply asked, “Can the horse make it?” Knowing the answer was yes, Don saddled the horse and headed to school.

Tragedy struck in the summer of 1940 when Don’s father passed away. His mother knew she and Don could no longer maintain the farm, so she sold the farm and took a housekeeping job with a family in St. Cloud where Don continued school. He finished his junior year in 1941, earning money during the spring and summer by working on local farms. The experience made him realize farming wasn’t the life he was looking for. Then he walked past the St. Cloud post office and saw his way out—a recruiting poster with a sharp looking Marine in his dress uniform. Since Don was only seventeen, he spoke to his mother and asked for her permission to enlist, which she gave. Then he headed to the recruiting office to join the Marines.

At the recruiting office, Don found a smartly dressed Marine looking every bit as good as the recruiting poster. Don told him he wanted to be a Marine, but the recruiter quickly dashed his plans. Although Don was in excellent physical shape and could outrun and outwork everyone he knew, the recruiter told Don that at 5’7” and 135 pounds, he was too small to be a Marine. Not to be deterred, Don walked down the hall to the Navy recruiter. There, in stark contrast to the spiffy Marine he’d just left, he found a Navy Chief Petty Officer with his feet up on his desk and his uniform jacket unbuttoned. The Chief asked Don, “Well son, what can I do for you?” Don told him he wanted to enlist, so the Chief asked him what he did. When Don said he worked on a farm, the Chief asked him if he worked with machinery. Don said yes and the Chief told him he had just the job for Don—aircraft mechanic. That was all Don needed to hear. He was ready to join the Navy.

On August 19, 1941, Don and one other recruit from the area boarded a bus and drove to the entrance processing station in Minneapolis. There he took his oath of enlistment and boarded another bus headed for boot camp at Great Lakes Naval Training Station north of Chicago, Illinois. They arrived at Great Lakes early on Wednesday morning, August 20, and immediately marched to the mess hall still wearing their “civvies” (civilian clothes). Breakfast consisted of baked beans, which the mess attendant piled onto Don’s metal tray. After he wolfed them down, a second class seaman (E-2) noticed Don wasn’t drinking his milk and told him to drink it. Don said he couldn’t drink milk and if he did, there would be a problem. The seaman told him to drink it anyway, so Don did as directed. He then threw up the milk and beans he had just consumed all over the table. His reward for being right was he had to clean up the mess, even though it wasn’t his fault. Needless to say, his enlistment was not off to a good start.

After breakfast, the new recruits marched to their barracks. Although some recruits were assigned bunks (called “racks” in the Navy), Don’s company had to sleep in hammocks like the ones found on older ships. All their possessions had to be stowed in their canvas duffel bags, known as seabags. To make their uniforms fit in their seabags, they had to neatly fold them and then tightly roll them into the smallest bundle possible. They then tied them with clothes stops so they wouldn’t unroll in the bag.

After breakfast, the new recruits marched to their barracks. Although some recruits were assigned bunks (called “racks” in the Navy), Don’s company had to sleep in hammocks like the ones found on older ships. All their possessions had to be stowed in their canvas duffel bags, known as seabags. To make their uniforms fit in their seabags, they had to neatly fold them and then tightly roll them into the smallest bundle possible. They then tied them with clothes stops so they wouldn’t unroll in the bag.

To test their packing skill, every week there was a seabag inspection, where the recruits had to lay all their clothing out on the floor. A lieutenant would then come by with a stick to test whether each recruit’s clothes were rolled tightly enough. During one such inspection, when the lieutenant arrived at the recruit next to Don, he didn’t like the way the recruit’s clothes were rolled, so he picked them up and tossed them out the window. The recruit then had to retrieve his clothes and re-wash them all by hand, which was the only way the recruits had to clean their clothes. Although Don’s clothes passed inspection, the incident motivated him and the other recruits to make sure their seabags were always ready for inspection. To this day, Don folds his socks the way he was taught at boot camp.

Because Don was in good shape when he arrived at boot camp, he had no problem with the physical training. He could run fast and do pushups and pullups, and unlike many of the recruits, he could swim well having grown up swimming and diving in Minnesota’s many lakes. He also played the accordion, which came in handy when his company Chief asked if anyone had any talent they could share with the other trainees. Don’s mother sent him his accordion, which he used to warm up a crowd of 5,000 waiting to watch an exhibition bout involving heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis. After Don finished playing, Joe Louis entered the ring and shook Don’s hand.

Don’s biggest disappointment came on payday. As a Seaman Recruit (the lowest Navy enlisted rank, or E-1), he expected to receive his full pay of $21/month. Instead, his first pay was just $12.67. When Don asked his Chief why the amount was so small, the Chief told him he had been charged for things like the bucket and soap he used to wash his clothes. Don was pretty sure someone was skimming something off the top of his pay, but there was nothing he could do about it. Aside from that, he thought his Chief trained his company well.

After graduating from boot camp in early October 1941, Don took leave to visit his mother and his buddies back in St. Cloud, Minnesota. Much to his chagrin, his mother wanted him to go with her to visit her mother in Centerville, Iowa. Don could think of nothing more boring and was upset he would not get to spend any time with his friends. Once he got there, though, he noticed a pretty fifteen-year-old girl named Darlene living across the street. On his last day in Centerville, he summoned the courage to speak to her and they ended up talking for a couple of hours. Then it was time for Don to go and he boarded a train for his next duty station in Jacksonville, Florida.

In mid-October 1941, Don reported to Naval Air Station Jacksonville for Aviation Machinist Mate school. He specialized in aircraft engine and propeller mechanics, becoming proficient in both areas. He also volunteered for combat aircrew training, which meant he learned how to be a gunner on aircraft that would operate from the Navy’s aircraft carriers. He proved to be an expert shot because of his experience hunting ducks in Minnesota.

On Sunday, December 7, 1941, Don returned to the barracks after church and lunch and learned Pearl Harbor had been attacked by the Imperial Japanese Navy. The news had an Orson Wells-like feeling, with no one believing it could be true. Once reality set in, the atmosphere was subdued, at least until the next morning when Don and the other sailors in his training section were mustered in their summer white uniforms for combat training. They soon found themselves crawling through the grass in their whites, none of them with weapons or any sense of the purpose for the training. From that point on, Don and the rest of the Navy were on a wartime footing.

In February 1942, Don departed Naval Air Station Jacksonville and reported to Naval Air Station Norfolk, Virginia, to continue his training. This advanced-level training included attending two six-week courses at the Curtiss-Wright Engine School and the Curtiss Electric Propeller School. Finally, by the summer of 1942, Don was ready for his first assignment. Initially, that was Marine Corps Air Station, Cherry Point, North Carolina, doing maintenance on aircraft hunting for German submarines off the East Coast of the United States. Then he and the men he was with, about 120 in total, departed Cherry Point by train on a non-stop trip to Naval Station Treasure Island, located all the way across the country on San Francisco Bay. They had no idea what their mission or ultimate destination was. All they knew was they were on a secret wartime mission.

Once at Treasure Island, Don and the other men of his unit loaded onto two rusty Dutch merchant ships. Thirty-two days later, they arrived in Noumea, New Caledonia, a French controlled island located approximately 750 miles off the east coast of Australia. More important, Noumea was located approximately 850 miles south of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, which was about to become the focal point of the Pacific War. Don’s team, now part of a composite unit identified as Acorn Red One and consisting of his aircraft mechanics and a battalion of Navy Seabees, loaded onto Navy transports and headed toward one of the most pivotal battles of World War II.

On August 7, 1942, the U.S. Marines landed on Guadalcanal and quickly captured and secured the main airstrip, renamed Henderson Field after Major Lofton Henderson, the first Marine aviator killed in the Battle of Midway. Two days later, Don and the other aircraft mechanics went ashore, waiting for the Seabees to finish work on Henderson Field and for the arrival of the U.S. aircraft that would operate from the airstrip when complete. By August 18, the field was ready and the first Marine squadrons flew in two days later. Don’s job was to keep the aircraft, dubbed the “Cactus Air Force”, flying so the pilots could attack Japanese Army forces on the island and Japanese Navy forces menacing the waters around Guadalcanal.

The conditions on Guadalcanal were horrendous. Henderson Field was under constant attack from Japanese ground forces, naval forces, and air forces, especially at night. Powerful Japanese battleships and cruisers periodically shelled Henderson Field from off the coast while every night Japanese bombers dropped bombs on the U.S. defenders below. The nighttime attacks by high-flying Japanese “Betty” bombers became so routine that Don and his friends reacted nonchalantly when the air raid siren wailed. Instead of heading immediately to their shelters, they posted a lookout to watch the searchlights sweeping the sky for Japanese airplanes. Only when the lights appeared directly above them would they take cover; otherwise, they would remain in their tents and try to get some sleep.

During one such attack, the assigned lookout yelled the searchlights were right above them and everyone scrambled out of their tents. Two Japanese bombs exploded nearby, hurling shrapnel everywhere. Fortunately, two big coconut trees that had been made into tables shielded Don from the blast. Otherwise, he is certain he would have been injured or killed by the bombs.

Don and his fellow mechanics did everything they could to keep the planes of the Cactus Air Force flying. Sometimes this meant overhauling engines or replacing propellers, while other times it meant scavenging parts from disabled aircraft or patching bullet holes with tape and painting over it. Don even helped resolve a problem with Major “Pappy” Boyington’s F4U Corsair’s supercharged engine and got to meet the Medal of Honor recipient in person.

Although Don worked on lots of aircraft, he was specifically assigned to maintain a particular Douglass SBD “Dauntless” dive bomber, which meant he also occasionally flew as a gunner on the plane. The theory was if he knew he was going to fly in the plane, he would be especially careful in maintaining it. He and the other maintenance personnel had to sleep under their assigned aircraft in case they were needed on short notice. This was terrifying because individual Japanese soldiers occasionally infiltrated the Marine perimeter around Henderson Field and slit the throats of the sleeping sailors. This memory is particularly difficult for Don even after the passage of eighty years.

When word circulated that the Japanese were going to make a concerted attack to retake Henderson Field, Don’s situation became precarious. Bulldozers pushed a protective berm of dirt around the airfield and Don and other members of his unit were issued M55 Reising guns, which looked like .45 caliber pistols with a rifle stock. Don was shown the defensive perimeter around the airfield and told when the first line of sailors was gone, his job was to fill in behind them and hold the line. Fortunately, the Marines held the perimeter against the Japanese attacks and Don never had to take a place in the line.

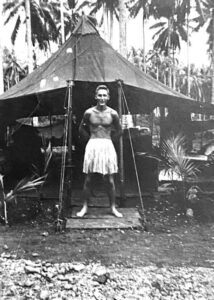

As if the constant attacks weren’t enough, tropical rains turned the ground into a deep, thick mud. Bugs and snakes were everywhere, and malaria and dysentery were rampant. Don took Atabrine to fight off malaria, but it turned his skin and urine bright yellow. Occasionally, he used the conditions to break the monotony and play jokes on his fellow sailors. One sailor, in particular, was afraid of snakes. Don found a length of rope on the dock, tied a string around it, and put it under the covers of his friend’s cot. When the friend fell asleep, Don pulled the string and the friend, thinking there was a snake in his rack, came flying off the rack to get away.

Once the situation on Guadalcanal stabilized, beer started to arrive on the island and it became a much sought after commodity. When some of Don’s friends learned a cargo ship had arrived with a shipment of beer, Don and his buddies took a small vessel known as a lighter out to the ship to commandeer their share of the beer. Just after the cargo ship deposited the first load of beer in the lighter, an Australian patrol boat came by blaring that a Japanese submarine was in the area and that the cargo ship should get underway immediately. Before the lighter could clear the area, the Australian patrol boat dropped depth charges on the suspected target. When they detonated, the lighter bounced up, tossing the beer in the water. Disappointed, Don and his friends made their way back to shore empty handed.

Although Don lost the beer, there were other ways to get alcohol. Some of the maintenance team noticed that on their way out to the aircraft on the flight line, they had to walk past a field where flares were stored. The flares were attached to small silk parachutes so that when the flare was fired from an artillery piece, it would slowly descend to the ground, lighting up the night sky as it did. Some of the men cut off these parachutes, painted the Rising Sun on them, and sold them to new arrivals on the island telling them they were captured Japanese flags. The men then used the money they made to buy whatever alcoholic beverage might be available.

Don had to be medically evacuated from Guadalcanal in June 1943 after coming down with malaria. He’d been on the island for ten months, surviving everything the Japanese had thrown at Henderson Field and the Cactus Air Force. Although barely nineteen and a Second Class Petty Officer (E-5), he’d already seen a lifetime of war. Yet for him, the war was just beginning.

Don spent the rest of June and all of July 1943 recuperating in a hospital in New Zealand. The winter weather was a welcome change from the tropical heat of Guadalcanal and his stay was uneventful. At the end of July, he returned to Noumea to find a way back to the States for his next assignment. He managed to get orders to hitch a ride on the USNS Rappahannock, a fleet oiler returning to Naval Base San Diego. On the way back, the ship stopped in Bora Bora, which Don describes as the most beautiful island in the world. Don arrived safely back in San Diego in August 1943.

Once back in the States, Don reported to Naval Air Station Alameda near San Francisco to await orders. While there, he had a second bout with malaria even worse than the first. After he was back on his feet, he made his way to Hawaii, where malaria hit him a third time. This time it was so bad he nearly died. Again, he recovered and caught up with his aircraft maintenance unit on the island of Roi-Namur in the Marshall Islands, which the Marines had already wrestled from the Japanese. From there they went to Tarawa, going ashore in November 1943, just after the Marines stormed ashore in what was to be one of the bloodiest battles in the Pacific War.

Before Don’s unit could begin its work maintaining aircraft on the atoll’s airfield, it had to assist burying over 5,000 of the Japanese defenders killed during the assault. The job got even worse when the smell of death started seeping from a Japanese bunker next to Don’s maintenance tent. Rather than cleaning out the bunker after it had been disabled, the Seabees simply bulldozed dirt over the top of it. Now it had to be opened and Don and the other members of his unit had to go inside and remove the human remains. The odor permeated their bodies. Even after showering and putting on new clothes, they smelled like death. So much so that when the unit entered the chow hall, everyone else left.

In early 1944 and after a brief ordeal with bed bugs on Kwajalein Island, Don and his unit moved to Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands, which had been captured by the Marines in January 1944. The atoll soon became a major forward staging area. The Navy prepositioned about sixty replacement carrier aircraft at the airfield as part of its theater-wide aircraft pooling strategy. U.S. Navy pilots flew their old or damaged aircraft to the airfield on Eniwetok and returned to their aircraft carriers flying the newer model replacement aircraft. Don and his team either fixed or jettisoned the old or damaged aircraft, making room for more new replacements. As a result, Don became an expert working on all types of Navy aircraft, including the SBD “Dauntless” dive bomber, the TBM “Avenger” torpedo plane, the SB2C “Helldiver” dive bomber, the F4F “Wildcat” fighter, and the F6F “Hellcat” fighter.

When Don first arrived on Eniwetok, though, his group, now numbering about twelve Second Class Petty Officers, had nothing to do because no planes requiring work had yet arrived. Accordingly, they set up their tent near a bakery and found a lieutenant who needed help unloading lighters bringing supplies ashore. In return, the lieutenant allowed them to “borrow” some of the supplies, including real potatoes, ice cream mix, and beer. They then traded some of their supplies to the bakery in return for even better goodies.

The arrangement worked great until one night when the group of twelve was cooking French fries and drinking beer kept on ice in empty ammo cans, they saw a man wearing a khaki uniform approach. This meant he had to be a Chief or an officer. It turned out to be even worse than that—he was the base Commanding Officer (CO). He asked the men how they were doing and one of the men, loosened up by the alcohol, said they were doing just fine and offered the CO a beer. He politely declined and when he learned the group had nothing to do, he put them to work on the airstrip fire crew.

Even though Don arrived on Eniwetok after the fighting was over, there were still grim reminders of the war. One evening, a bomb-laden Navy PB4Y (the Navy’s version of the four-engine B-24 “Liberator” bomber) roared down the runway for takeoff when two of the engines failed. The bomber tore through the pool of parked carrier planes, destroying around twenty-five aircraft and killing everyone on board the PB4Y. A Seabee used a bulldozer to roll the unexploded bombs from the plane away from the burning aircraft, which came to a stop only fifty to sixty feet from Don’s maintenance tent.

Don was still working on Eniwetok when the war with Japan ended on August 15, 1945. He didn’t have long to celebrate because at the end of August he received a telegram from the Red Cross informing him his mother had passed away. To see if he could return home to be with family, he went to speak with his commanding officer. His commanding officer gave him orders to the Naval Air Technical Training Center (NATTC) on the south side of Chicago and he departed soon after. His service in the Pacific and World War II was officially behind him.

Don reported to NATTC in October 1945 as an aviation maintenance instructor. In February 1946, NATTC relocated to Naval Air Station Millington, Tennessee, just outside of Memphis. Before Don moved with it, he wrote to Darlene, the young woman he’d met in Iowa in 1941 after boot camp. After a few drives from the south side of Chicago to visit Darlene in Iowa, Don and Darlene fell in love and were married on Christmas Day 1945. When Don moved to Memphis in February 1946, Darlene went with him.

There was lots to do in Memphis once Don arrived. With the aviation maintenance school having just moved there, everything had to be set up from scratch. Don, now a First Class Petty Officer (E-6), worked in the propeller section and continued to improve his maintenance proficiency by attending various factory schools. He remained at NATTC until September 1949, when he transferred to the Fleet Air Service Squadron (FASRON) at Naval Air Station Oceana in Virginia Beach, Virginia. Again, he was assigned to the propeller shop, where he was a recognized expert technician. In fact, the Chief in charge said, “Gohman, you run the shop and I’ll sign the paperwork.”

Once the Korean War broke out on June 25, 1950, the immediate demand for people, ships, and carrier aircraft threw Oceana’s squadron maintenance schedules into chaos. Don continued to work on F4U Corsairs, Douglas AD “Skyraiders”, and even the new F-9 “Panther” jet fighter. However, in 1951 the personnel demands of the war caught up to him and he was given the choice of either going to sea or returning to the propeller shop at NATTC as an instructor. It was an easy choice—in October 1951, Don returned to Memphis with Darlene. He stayed there until the summer of 1954, when he reported to Commander, Fleet Air Japan at Naval Air Station Atsugi, located twenty-seven miles southeast of Tokyo.

Don’s job at Commander Fleet Air Japan was mammoth. He was responsible for tracking the maintenance status of every Navy airplane in the Western Pacific theater and scheduling its maintenance at factory specified intervals. Given the information he had available to him, his job required a Top Secret clearance. He was also in charge of the factory service representatives, who would fly out to the carriers or the surrounding airfields to perform maintenance on aircraft when the Navy’s sailors encountered problems they could not fix on their own. When the problem stumped even the factory service representatives, Don would fly out to fix the problem.

Darlene and their one-year-old daughter, Becky, eventually followed Don to Atsugi. She and other Navy wives boarded a ship in Santa Clara, California, and sailed across the Pacific to Japan. The trip was miserable, with seasick kids, stopped toilets, and children on leashes whenever they went on deck so they wouldn’t fall overboard. Once Darlene and Becky arrived, they lived with Don out in town in Atsugi, but eventually they were able to live on base and enjoy its American amenities.

One thing Don is most proud of from his time in Japan was climbing Mt. Fuji, the 12,000-foot volcano overlooking Tokyo. Don set out with three members of his staff and twenty-seven other climbers. It started raining when they reached 6,000 feet and sleeting at 8,000 feet. It was so miserable, all but Don and his three companions turned back. Eventually, the clouds broke and they had a beautiful view of the expansive Kanto Plain below. Don still has the climbing stick he used to make the climb, known as a “Fuji stick”. Now he uses it whenever he talks to groups to encourage them to never give up.

Don worked at Commander Fleet Air Japan until November 1957, when he again returned to NATTC in Memphis. This time he worked with engine analyzers monitoring spark plugs firing on radial engines. In 1961, he started transitioning into the jet engine field. In 1962, he promoted to Chief Petty Officer (E-7) and earned the Navy’s Schoolmaster of the Year Award after competing against over 2,800 instructors from across Naval aviation worldwide. One of the perks of the award was he got to fly to Mobile, Alabama, several times to appear on a Sunday morning science and physics television show hosted by a noted physicist. Back at NATTC, Don set up the maintenance courses for the T-56 turboprop engine before transferring to his next command.

In February 1963, Don reported to Midway Island in the central Pacific Ocean, located 1,300 miles northwest of Oahu. He was assigned to AIRBARSRON TWO which flew a continual line of the four-engine WV-2 Super Constellation surveillance aircraft on a racetrack course between Midway and the Aleutian Islands. In the days prior to satellite surveillance, these long-range early warning planes painted a constant picture of surface and air traffic in the central Pacific, helping protect Alaska, Hawaii, and the West Coast of the United States and Canada from a possible surprise attack from the Soviet Union. As it had been for so many years, Don’s job was to keep the aircraft flying around the clock, seven days a week. Don also qualified as a junior flight engineer, which allowed him to fly on some of the squadron’s surveillance missions to the Aleutians. The job was stressful and demanding, but once again Darlene, Becky, and now his son, Mark, joined him there in the summer of 1963. They kept themselves entertained by watching the many birds on the island, including the giant albatross known as the Goony bird.

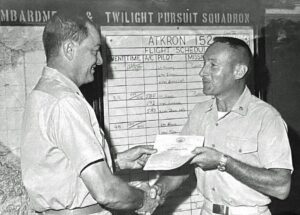

In July 1964, Don transferred to Attack Squadron ONE FIVE TWO (VA-152) at Naval Air Station Alameda in the San Francisco Bay area. The squadron operated the Douglas A-1 Skyraider (formerly the AD Skyraider), which was a powerful single-engine propeller driven close air support aircraft capable of delivering 8,000 pounds of ordnance on enemy targets with great precision. Don was the squadron’s Quality Control Chief Petty Officer, meaning he was responsible for making sure the maintenance was conducted according to standards.

Don deployed with the squadron aboard the aircraft carrier USS Oriskany (CV-34) in April 1965 to participate in the quickly escalating Vietnam War. The ship’s squadrons flew missions over Vietnam from May 1965 through the end of November 1965, before returning to San Diego on December 16, just before Christmas. During the cruise, Don became good friends with the ship’s Catholic Chaplain, Lieutenant Commander William J. Garrity. During a deep discussion in the Chief’s Mess one evening, Chaplain Garrity said he would give his life for the men on the ship, just as Jesus had done for all men. Don pressed him on it, but one year later Chaplain Garrity proved good to his word, helping to lead a dozen pilots to safety after being caught in a horrific blaze that almost sunk the ship in the Gulf of Tonkin off the coast of Vietnam. Chaplain Garrity died in the fire after going back to try to rescue even more trapped pilots. During an Honor Flight Don took to Washington, DC, in October 2022, he made a point of honoring Chaplain Garrity by finding his name on the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial Wall.

Now a Senior Chief Petty Officer (E-8), Don detached from VA-152 in 1966 and returned to NATTC in Memphis. This time he was assigned to the teachers training section, where he screened students to be prospective instructors. Once selected, the students went through a twelve-week course to qualify as an instructor. Don’s job subsequently expanded to be the head of the Quality Control Division, evaluating the performance of the instructors. Finally, he was put in charge of the full operation, covering screening, teaching, and evaluating all NATTC instructors. This meant he was responsible for 1,200 instructors and 6,000 students—it was the biggest job Don held in the Navy and he loved it. It also helped him promote to Master Chief Petty Officer (E-9), the highest enlisted rank in the Navy, as did his efforts to broaden his professional education in areas that would help him be a better leader. This included completing the Third Class Personnelman correspondence course, working with sailors taking the Second Class Hospital Corpsman course, becoming certified in CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) and lifesaving with the Red Cross, earning his GED (graduate equivalency degree), and completing a Psychology I course at the University of Memphis.What he is most proud of during this tour, though, was that he tutored three candidates from his command over three years for the Navy’s Schoolmaster of the Year Award and two of the three won the award.

Don retired from the Navy in July 1971 after a distinguished thirty-year career. Because he loved to teach and be around teachers, he accepted a job as a Building Engineer for the Memphis City Board of Education. As a Building Engineer, he was responsible for keeping his assigned school fully operational so the teachers could focus on teaching their students. When the teachers learned about Don’s background, they often brought him into class to work with the kids. He even made a jet engine for one science class and helped other teachers teach about electricity. Don retired from Memphis City Schools in 1986 after fifteen years.

Although Don had already earned a well-deserved retirement, he had one more job to do. He had heard through his church that the Monastery of St. Clare, a community of nuns following the example of St. Clare of Assisi, needed someone to help take care of the monastery. When Don arrived at the community, he spoke with the Abbess about the position. She told him she could not pay him much and he said that was okay. Then she said, “In fact, I can’t pay you at all.” It didn’t matter to Don—the nuns needed help and he knew he was the right person. He accepted the position and worked there for 33 years, finally retiring at the age of 95!

Don now lives outside Memphis with his daughter, Becky. Sadly, his beautiful wife, Darlene, passed away on Christmas Day 2018, 73 years to the day after they were married. Don treasures every day he had with Darlene and gives her and other military spouses a special salute. They hold their families together when their servicemember spouses are deployed in far off places. They work long hours and raise their kids without any recognition or awards. Yet their contribution is every bit as crucial and patriotic toward our national defense as their servicemember spouses’. Don is passionate about the importance of military spouses and wants all to realize the important role they play.

In October 2022, Don participated in an Honor Flight from Memphis to Washington, DC, recognizing him for his years of service to our country. During the trip, he visited the World War II Memorial, the Korean War Memorial, and the Vietnam War Memorial, representing the three conflicts spanning his career. Now as he looks to the future, he can’t wait for April 8, 2024, because he will be at ground zero for a 99.9% solar eclipse, not to mention he will have celebrated his 100th birthday the month before.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Master Chief Petty Officer Donald Gohman, U.S. Navy (Retired) for his thirty years of distinguished service to our country. From the epic battle for Guadalcanal in World War II to helping USS Oriskany’s aircraft fly combat missions during the Vietnam War, Don served and sacrificed without condition or complaint. From the bottom of our hearts, we say thank you for your service, shipmate. We wish you fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Don’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

November 12, 2022 @ 10:55 AM

Profound Thanks for the service of these dedicated men and women of our military!

November 12, 2022 @ 3:55 PM

Randall, thanks for reading Don’s story, and for your service, as well. V/r, Dave Grogan

November 16, 2022 @ 5:10 PM

Thanks for your service

November 26, 2022 @ 10:43 AM

Wayne – thanks for reading Don’s story!