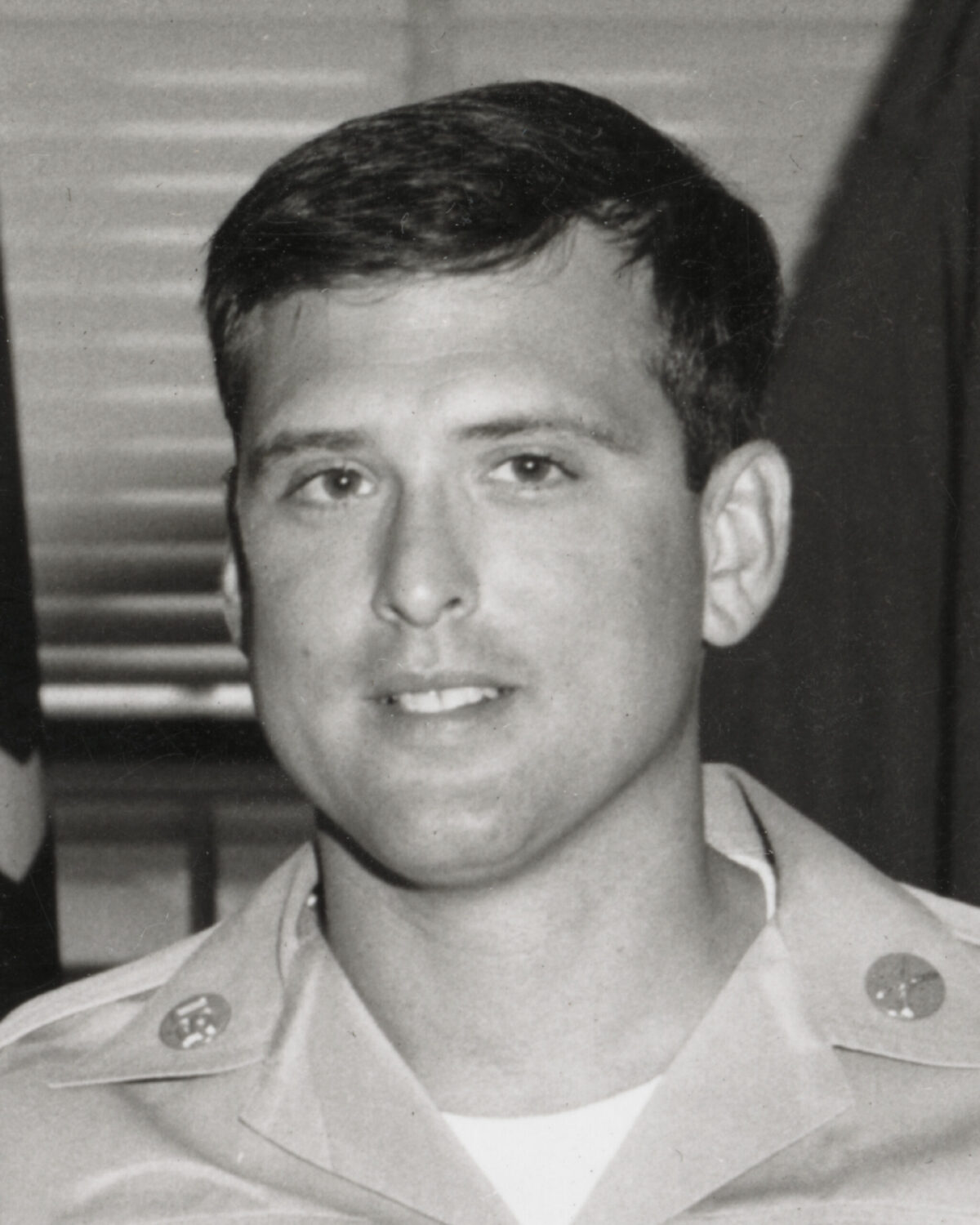

Sergeant Ron Haeberle, U.S. Army – A Photo of Future Hope

Photographs are like time capsules, forever freezing a moment in time. They provide us with a window into the past, documenting our history in a way the written word cannot. Yet for Sergeant Ron Haeberle, U.S. Army, a photograph he took on March 16, 1968, did more than just look back in time. It foretold the future—a future built on courage and survival and shining as a beacon of hope to all who see and understand it. Now, over fifty years after Ron’s Nikon camera captured the image, it serves as an inspiration for Ron in every aspect of his life. This is Ron’s story.

Ron was born and raised in Northeastern Ohio. His father worked as a superintendent for the Republic Steel Corporation and his mother worked as a secretary in the Fairview Park, Ohio, public schools. Ron and his sister attended Fairview Park High School, where Ron played football and ran track. He graduated in the spring of 1960 and began to work for the Fairview Park School System to save money for college. In the fall of 1962, he enrolled at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, majoring in photography and aspiring to become a photojournalist.

During Ron’s fourth year at Ohio University, he changed his status to part-time for the spring semester of 1966. With U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War escalating daily, the university’s Registrar’s Office reported the change in Ron’s enrollment status to the federal government. The result was Ron received a draft notice, directing him to report immediately for induction into the military. Ron asked for a three-month delay so he could complete his degree, but with the war’s insatiable appetite for young men, his request was denied.

In April 1966, Ron drove home from Athens and, after a short visit with his family, reported as directed to the Armed Forces Examining and Entrance Station in downtown Cleveland. There he passed his physical and together with the other draftees, was officially inducted into the Army. He and the other draftees then marched in a makeshift formation to the Terminal Tower on Public Square, with onlookers gawking all the way. At the Terminal Tower, they boarded a Rapid Transit train to Cleveland Hopkins Airport for a flight to Atlanta. Once they arrived in Atlanta, a waiting bus drove them to Fort Benning, Georgia, for Army Basic Training.

In-processing began immediately with the new arrivals getting haircuts and uniforms and receiving their barracks and training company assignments. As Ron expected, Basic Training included a significant physical component, but he did not find it difficult because he had been an athlete in high school and stayed in shape throughout college. In fact, his athletic prowess paid off more than once because it allowed him to win various contests within the company, the prize being he didn’t have to stand “KP” (kitchen police) duty, washing pots and pans and doing other similar chores in the chow hall.

After eight weeks, Ron graduated from Basic Training. He followed graduation with a short leave period at home in Northeast Ohio, then he reported to Fort Ord in Monterey, California, for Advanced Individual Training (AIT) to become a mortarman. In the eight-week course at Fort Ord, Ron became proficient at firing the M29 81-millimeter mortar, which could fire a high-explosive mortar round at a target located over two miles away. Training began with the basics, with the novice mortar crews learning never to put a foot under the baseplate of their mortar to try to stabilize it or the concussion would crush their foot when the mortar was fired. Once proficient, the soldiers participated in search and destroy mission training, where the trainees learned to seek out and engage enemy units.

Ron also learned to fire a .50-caliber machine gun. Interestingly, a chain linking the barrel of the gun to the firing platform prevented the barrel from elevating above a certain level. When the trainees asked why the chain was necessary, the instructors pointed to California’s Highway 1 off in the distance and said if the barrel was elevated too high, rounds from the machine gun might impact cars on the highway. After looking up and seeing the vehicles driving along the highway, Ron was amazed the weapon was being live-fired in such a confined training area.

When it came time for AIT graduation in the late summer of 1966, the graduating privates lined up to receive orders for their follow-on tours. Although many soldiers received orders to Vietnam, Ron did not. Instead, he was assigned as a mortarman for the 11th Infantry Brigade, which had just reactivated on July 1, 1966, at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii. Ron reported to Schofield Barracks, located about twenty-two miles northwest of Honolulu, in September 1966.

After Ron arrived, he began exploring the post and meeting the soldiers he would be working with. Harkening back to his desire to become a photojournalist, he took pictures of his new comrades in arms and of the barracks they lived in, documenting their daily lives. About a week into his assignment, the brigade commander saw him taking pictures and asked what he was doing. Ron told him about his background at Ohio University and that he had majored in photography.

The conversation gave the brigade commander an idea. As the 11th Infantry Brigade had just recently reactivated, he could use someone like Ron to document the brigade’s activities and help provide publicity for the brigade’s accomplishments. He asked Ron for his name and then strode away. A few days later, Ron received a notice – he was being transferred to headquarters to be a one-man public information office for the brigade. He would never fire a mortar again.

Ron loved his assignment in the newly created brigade public information office. Not only did it mean working at brigade headquarters, but he also was assigned his own jeep and had unrestricted use of the base photo lab. His official responsibilities included taking pictures of the soldiers in action during brigade training and documenting other milestones and events like promotion and award ceremonies. After developing the pictures, Ron added captions to the photographs for publication in the brigade newspaper. He also sent news releases and photos of individual soldiers to the newspapers in their hometowns to keep their families and communities apprised of their favorite sons’ accomplishments.

Ron took full advantage during his off-duty hours of living in Hawaii. Oahu was not nearly as developed as it is today and there were many things to explore. Ron tried surfing on Waikiki Beach, hiked around Diamond Head, and tried everything the island had to offer. He particularly enjoyed scuba diving, although on one occasion at Hanauma Bay things almost turned out badly. While diving at a depth of 100 feet, he ran out of air and had to “buddy breathe” from a companion’s air tank until they reached the surface. At that point, they were dangerously close to the swift Molokai current that could sweep them out to sea. They managed to make it back to shore safely, albeit with a lot of cuts and scrapes to show for their ordeal.

Although the 11th Infantry Brigade was intended to remain in Hawaii to be part of the Army’s strategic reserve, in 1967 the need for additional combat troops in Vietnam resulted in the brigade being designated for deployment to Vietnam. As the brigade was not scheduled to depart until late 1967 and Ron’s two-year draft commitment would expire in April 1968, he was told he did not have to go to Vietnam with the brigade. After hearing so much about Vietnam in the news media and reading about it in magazines, Ron thought it important to deploy with the unit and finish out his tour, so he volunteered to go. The brigade approved his request.

With the exception of an advanced element that flew to Vietnam to prepare for the arrival of the full brigade, the brigade and its equipment departed Hawaii by ship in December 1967. Ron recalls the voyage as long and boring, but at least the seas were calm over the entire route. They arrived in Qui Nhon, a coastal town located about 400 miles northeast of Saigon in the Republic of South Vietnam. The brigade unloaded and then proceeded by convoy via Highway 1 due north along the coast to its operating base at Duc Pho. Ron remembers looking from his jeep and seeing the Vietnamese people, their villages, and the terrain for the first time. He felt like he was now living the experience he’d previously only read about in newspaper and magazine stories about Vietnam and its people.

The experience also highlighted for Ron a deficiency in the training he and the other members of his brigade received, or in this case, did not receive. What they knew about Vietnam and its people came almost exclusively from newspapers and magazines. The only official introduction to Vietnam and its people came after they arrived in country. That brief, conducted by South Vietnamese soldiers and lasting about an hour, focused on the dangers of operating in South Vietnam. It warned of encounters with Viet Cong guerilla fighters and watching out for booby traps. It taught them nothing about how to interact with the Vietnamese people—the people they were ostensibly there to help.

The brigade arrived in Duc Pho in time to celebrate Christmas. It was attached to the 23rd Infantry Division (known as the “Americal Division”) and began operations shortly thereafter. Ron was assigned to the Headquarters Company as part of a now much larger Public Information Office consisting of three officers and nine enlisted soldiers including Ron. Ron’s main function was to accompany brigade units, usually at the company level, on missions in the field to document their activities on film. He often paired with his friend, Army reporter Specialist 5 Jay Roberts, who contributed to the effort by writing stories about the missions.

The new year in 1968 got off to a rough start. On January 31, 1968, the North Vietnamese launched the Tet Offensive, simultaneously attacking cities and installations across South Vietnam. Although U.S. and South Vietnamese forces soundly defeated the North Vietnamese before the end of February, the offensive resulted in many casualties and proved to be a turning point in U.S. public opinion for the war. By March, though, Ron was nearing the end of his two-year Army commitment and getting close to going home and returning to civilian life.

Then, on March 15, 1968, Ron attended a brief that indicated Charlie Company of the 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, 11th Infantry Brigade, would be conducting an operation in the vicinity of the hamlet of My Lai (also known as My Lai 4). The operation was intended to search out and destroy remnants of the 48th Viet Cong Battalion, which were thought to be operating in the area. Ron was initially concerned because a company was being sent to attack an enemy battalion, but the briefer stressed they only expected to find remnants of the Viet Cong battalion, not the entire battalion.

As a “short-timer” with only one month left in his Army career, Ron did not have to go on the mission. However, just as he did when the 11th Infantry Brigade deployed to Vietnam, he volunteered to accompany Charlie Company to photograph the operation. As had been the case on similar missions in the past, Jay Roberts would partner with Ron on the mission.

Early the next morning on March 16, 1968, a helicopter ferried Ron and Jay to My Lai 4 to document Charlie Company’s mission. As a result, they were on hand to record one of the darkest days of the Vietnam War for the United States. To their horror, they witnessed Charlie Company murder all the men, women, and children the unit found in My Lai 4. When newspapers and magazines published Ron’s photographs of the massacre in November of the following year, a shocked world saw Charlie Company’s atrocities firsthand.

Eleven days after photographing My Lai 4, it was time for Ron to return to the United States as his two-year commitment was nearing its end. He departed Vietnam on March 27, flying to Seattle, Washington, for out-processing at Fort Lewis. He spent several days at Fort Lewis doing paperwork and finally receiving his honorable discharge in April 1968. By the time of his discharge, Ron had risen to the level of sergeant (E-5) and was twenty-six years old.

After the Army, Ron returned to his family in Northeast Ohio. He took a job at Republic Steel before completing his degree at Ohio University in the fall of 1969. After graduating, he started a career in the business world, working for a range of companies until he retired.

Ron is also an ardent adventure traveler. He loves to roam the backroads, away from the tourist traps, so he can meet and interact with the people from the area he is traversing. This led him to return to Vietnam in 2000 to bike the 646-mile trek from Hue to Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City). He’s done similar bicycle trips in Southeast Asia, totaling over 2500 miles.

In 2011, Ron received a message via Facebook that changed his life. The message was from a German cinematographer doing a documentary on a survivor of My Lai 4. He asked if Ron was the My Lai 4 photographer and Ron told him he was. The cinematographer then informed Ron that two children Ron had photographed on a trail in March 1968 were still alive. Ron assumed both had been killed during the massacre. The children, Duc Tran Van and his younger sister, Ha Thi Van, were now adults, with Duc living in Germany and collaborating with the cinematographer on the documentary. The filmmaker asked if Ron would be interested in meeting Duc. Ron was, so much so that he invited Duc and the cinematographer to visit his home in Northeast Ohio. Duc followed-up with an email to Ron a few days later reiterating he was the boy in Ron’s photo.

Duc and the cinematographer visited Ron in September 2011 and they immediately bonded and became friends. After listening to Duc’s account of the events of March 16, 1968, Ron was convinced Duc was the little boy lying on the ground and protecting his sister in the photograph. Duc described a helicopter with white teeth overhead, flying above them on the road. Ron went back and looked at the sequence of pictures he’d taken surrounding the photo of Duc and his sister and saw that indeed, a Huey helicopter with shark’s teeth painted on its fuselage was flying overhead.

Duc told Ron he was trying to escape from My Lai 4 carrying his fourteen-month-old little sister, Ha, who had been wounded in the abdomen. He was trying to get to his grandmother’s village, located about four kilometers from My Lai 4, when they were photographed on the trail. They eventually made it, but their lives were very difficult afterwards. Duc’s mother and two of his four sisters were killed during My Lai 4 and his father did not survive the war. His grandmother was very poor, so they had to scrounge just to find enough to eat. Still, Duc was able to finish school and in 1983, emigrated from Vietnam to East Germany, where he became a machinist. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, he moved to Remscheid, Germany, and continued a successful career repairing machinery. It was then that he met up with the German cinematographer and agreed to work with him on the documentary.

One month after Duc and the cinematographer visited Ron in Northeast Ohio, Ron accompanied them on a trip to My Lai 4. They visited the museum there and found some of the surroundings, including the remains of burned-down buildings, looking just like the scenes Ron captured in his photographs. Ron also met Duc’s sister, Ha, who grew up to be a schoolteacher and now lives in Quang Ngai, not too far from My Lai 4.

Ron, Duc, and Ha consider each other as family. For Ron, learning Duc and Ha had survived the massacre finally brought a measure of hope to an otherwise total human tragedy. Their survival, which was nothing short of miraculous, demonstrated the strength of their spirit and their incredible courage in the face of insurmountable odds. Their example inspires Ron each and every day. For example, Ron recently helped organize efforts to raise $28,000 for flood and typhoon victims in Vietnam. The funds were distributed in two Vietnamese provinces in January 2021.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Sergeant Ron Haeberle, U.S. Army, for his service during the Vietnam War. Knowing the headwinds would be great, he helped bring truth to the public when it needed to be told. Moreover, he continues to build bridges across the divides that separate people and understanding. For all he has done and continues to do, we wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Ron’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

June 18, 2022 @ 12:33 PM

Great pictures and awesome story…..was a two-time Viet Nam Veteran….Grew up on Long Island, NY and also was a 30 yr. cop

June 19, 2022 @ 7:29 AM

Stephen – thanks for reading Ron’s article and for your service as a veteran and in the police.

June 26, 2022 @ 5:29 PM

A horrific tragedy, captured only because of the bravery Ron & Jay presented when following through with their hopes and dreams of informing the world. Great article… a terrific piece of journalist history.

July 1, 2022 @ 5:44 PM

Madeleine – Thank you for reading Ron’s story and for your kind comments.

June 19, 2022 @ 10:07 PM

That was an excellent story , the story teller did great on explaining what he saw,

June 21, 2022 @ 8:18 AM

Wesley – thanks for taking the time to read Ron’s story.

June 21, 2022 @ 12:34 AM

I graduated HS in 1969. I had 3 brothers go to Vietnam. Two were there at the same time, 15 miles a part. One brother served in Vietnam, 3 terms. My Mother would not watch the nightly World News because they would show pictures or film of Vietnam. I was glad in 1974 when it was over. I appreciated reading this article.

June 21, 2022 @ 8:19 AM

Kay – thanks for taking the time to read Ron’s story and for your brother’s service in Vietnam.

June 24, 2022 @ 9:45 AM

Thank you for your service from another Jungle Warrior, Delta 4/3, Welcome Home. When you have time read the excellent story David did on me.

July 1, 2022 @ 5:45 PM

Thanks Rick – I’ll be sure Ron sees your comment.