Seaman 1st Class Edward Collins, U.S. Navy – Serving on an Aircraft Carrier in the Pacific War

In the 1965 World War II movie classic In Harm’s Way, the character Commander Paul Eddington, played by Hollywood legend Kirk Douglas, describes the coming war in the Pacific as “a gut bustin’, mother-lovin’ Navy war.” All the men who served on ships in the Pacific theater from the start of the war at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, to the end of the war in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945, know just how true that statement was. One of those men was Seaman First Class Edward Collins, U.S. Navy, who joined the fray in 1943 aboard the USS San Jacinto (CVL-30), a light aircraft carrier that participated in all the major Pacific War Navy campaigns in 1944 and 1945. Manning his station on the USS San Jacinto’s flight deck during everything from hurricanes to kamikaze attacks, he lived and breathed the history that has inspired generations of Americans ever since. This is his story.

Ed Collins was born in the tiny coal mining town of Dehue, West Virginia, in 1925. His father, Albert, was a life-long coal miner who spent forty years in the mines, rising to the position of mine foreman. Albert and his wife, Myrtle, made their family’s home on the West Virginia side of the town of Amonate, the main part of which was located just across the border in Virginia. The location was so remote that schools were few and far between. This meant Ed and his brother and sister had to ride a bus through the winding mountain roads to their school in War, West Virginia, over ten miles away.

Ed graduated in 1942 from Big Creek High School in War, West Virginia, just six months after the Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor, bringing America into World War II. After graduation, Ed followed in his father’s footsteps and began working in the coal mines. However, when he turned eighteen in January 1943, he saw enlisting in the military as an opportunity to get out of the mines and do his part in the war. He also knew he would be drafted soon anyway, as all young men were being drafted once they turned eighteen. When Ed told his parents of his decision, they fully supported him. His older brother was already in the Army and the entire country enthusiastically supported the war effort.

Knowing he had his family’s support, Ed headed for the recruiting office in War around April 1943. He had two options, Army and Navy, but Navy seemed like the right way to go. He committed to the Navy and went home to await instructions. One month later, he received the call and reported back to the recruiting office as directed. From there, he and the other new recruits from the area were loaded onto a bus headed for Wheeling, West Virginia, where they raised their right hands and formally enlisted. Then it was off by bus to Naval Station Great Lakes north of Chicago, Illinois, for boot camp.

Boot camp lasted six weeks. Ed’s days began with a mile run around 6:00 a.m. before breakfast, followed by “marching, more marching, some schooling, tests, shots, and more marching.” Despite this rigorous schedule, Ed did not find boot camp difficult having played football and basketball and run track in high school and having worked in the coal mines of West Virginia. After he graduated as a newly minted Apprentice Seaman (E-1), he and the other new sailors were granted a week of leave. Ed used the time to visit his family and then returned to Naval Station Great Lakes to join thousands of other new sailors waiting for their next assignments.

At Great Lakes, Ed learned he had been designated for aviation support training. That meant he and other similarly designated sailors were off for Quonset Point Naval Air Station, located approximately twenty-five miles south of Providence, Rhode Island. There Ed learned how to prepare the Navy’s new Grumman F6F fighter plane for combat missions, working closely with the new pilots training to fly them.

After completing his aviation support training, Ed traveled to Norfolk, Virginia, to report aboard USS San Jacinto (CVL-30), a new light aircraft carrier launched on September 26, 1943, and commissioned on November 15, 1943. The ship, which could carry forty-five combat aircraft, was originally intended to be a light cruiser. However, after Pearl Harbor, the need for carrier-based airpower, which could take the fight to the enemy at a much greater distance than surface combatants could, caused the ship to be converted while under construction to a light aircraft carrier.

On January 14, 1944, Ed sailed with the ship on its shakedown cruise. The twenty-seven Hellcat fighters and nine TBM Avenger torpedo bombers of Air Group 51 landed onboard soon afterward and the ship headed for the Caribbean, where the crew gained experience with the new ship’s systems and learned the art of launching and recovering aircraft while underway. On April 2-3, 1944, the ship transited the Panama Canal, beginning its two-year Pacific War campaign. The ship subsequently made stops in San Diego and Hawaii, which Ed remembers fondly even though every place out in town was overrun with servicemembers.

In early May 1944, USS San Jacinto joined Task Force 58 in the Marshall Islands, where its aircraft participated in the fight for the first time by providing fighter cover for task force ships and support for air strikes against Japanese forces on Marcus Island and Wake Island. Throughout these and all subsequent combat operations, Ed played an important role in keeping USS San Jacinto’s planes flying. Applying what he learned at Quonset Point Naval Air Station, Ed served as a plane captain responsible for making sure his assigned F6F Hellcat fighter was ready to go for the pilot when it came time to launch on a mission. This meant doing a pre-flight check of the plane’s gas and oil levels, maneuvering the plane to the correct spot on the flight deck before launch (take-off) and after recovery (landing), starting the plane’s engine to warm it up for the pilot, and making sure the plane was properly tied down so it would not move or be damaged during rough seas.

Ed also worked closely with the pilots assigned to his aircraft. He checked their parachutes and gear and helped them get hooked up inside the cockpit. He really admired the pilots, who looked too young to be responsible for flying the planes on such dangerous missions. He thought they were incredibly brave and describes them all as “nice kids”. Although Ed did not know him at the time, one of the nice kids piloting an Avenger torpedo bomber from the USS San Jacinto was Lieutenant Junior Grade George Herbert Walker Bush, who would later become the forty-first President of the United States. On September 2, 1944, Japanese anti-aircraft fire hit Bush’s plane during a mission over the island of Chichi Jima. Bush ordered the crew to bail out over the ocean. Bush survived and was rescued by the submarine USS Finback. The other two crewmembers were never found.

Ed’s job was dangerous, too. As the carrier prepared to launch aircraft, its flight deck was crowded with planes and their whirring propellers as the pilots waited for their turns to take off. If a sailor was not paying attention, he could inadvertently walk into a propeller and be killed instantly. On top of that, throughout Ed’s time in the Pacific, the USS San Jacinto was constantly under attack from Japanese aircraft, including kamikaze suicide planes. During April 1945 in operations supporting the Marines landing on Okinawa, Ed remembers a kamikaze heading for the ship until it was hit by the ship’s anti-aircraft fire at the last minute, shooting off a wing. The plane missed the ship by only fifty feet, exploding as it hit the water. Debris from the kamikaze landed on the flight deck and had to be removed to allow air operations to continue.

On another occasion, Ed was sitting in his assigned F6F Hellcat just after it had been spotted to its position on the flight deck when another plane made a hard landing and crashed into the parked planes. The ensuing chain of collisions started to push Ed’s plane over the side of the ship. Luckily, the wing of Ed’s plane lodged against a gun mount, preventing the plane and Ed from plummeting into the sea. Miraculously, Ed walked away from the incident uninjured.

Another of Ed’s important responsibilities involved damage control. Whenever the ship was at General Quarters and Ed wasn’t otherwise performing his plane captain duties, he was assigned to a firefighting team on the flight deck. This meant if a bomb, torpedo, or kamikaze attack damaged the ship, Ed and the other members of his team were responsible for maneuvering a powerful firehose stowed just below the edge of the flight deck to the site of the fire to put it out. Aircraft carriers like USS San Jacinto, with their stockpiles of bombs and torpedoes always at the ready to arm their embarked aircraft, were particularly vulnerable to fire. If flames were not brought under control quickly, these munitions could set off violent explosions that would doom the ship. Ed and his team knew their lives and those of the entire crew depended on their efforts, so they took their damage control responsibilities very seriously.

Enemy attacks weren’t the only dangers Ed had to deal with. On December 18-19, 1944, after USS San Jacinto and other ships of Admiral “Bull” Halsey’s Third Fleet conducted air raids against Japanese forces on the Philippine island of Luzon, the ships were caught in a powerful typhoon with wind speeds estimated at 160 miles per hour. As the storm hit, Ed managed to get his fighter tied down on the flight deck’s fantail. As he walked away from the plane, he saw a giant wave heading for the ship. The ship tried to turn into it so that its bow would slice through the wave, but the turn started too late. When the wave hit, the ship rolled steeply to one side, causing Ed to drop to the deck to hang on for dear life. Planes on the flight deck not tied down rolled off the deck and fell into the sea. Then the ship rolled back the other way and Ed had to shift his position to keep from sliding off the flight deck in the other direction. Below the flight deck on the hangar deck, a plane broke free and careened into other planes as the ship rocked back and forth from the incessant waves, destroying seven aircraft. The damage USS San Jacinto sustained in the storm took it out of action for about a month as repairs were made by the repair ship USS Hector (AR-7) at Ulithi atoll, the U.S. Navy’s western Pacific staging area. Other ships weren’t so lucky. Three destroyers sank, almost 800 sailors were killed, and many other warships sustained major damage. Admiral Halsey later faced a court of inquiry for allowing the fleet to be caught in the storm.

When USS San Jacinto was not under threat of enemy air attack (the ship always had to worry about Japanese submarines), life onboard was routine. Ed slept in a rack (the Navy term for a bunkbed) stacked three high. He had a small locker to stow his personal belongings, which were by necessity minimal. Up by 6:00 a.m., he would eat breakfast on the mess deck with the other sailors. His normal fare consisted of beans and a sweet roll, but not the coffee that became a staple for so many of his shipmates. Then it was off to his plane captain duties, keeping his assigned F6F Hellcat fighter clean and in combat ready condition for its pilot to fly. Lunch and dinner were events he looked forward to as they afforded him an opportunity to relax, plus he found the food overall pretty good. He could retire whenever his work was finished and he was done for the day—lights out came at no set time.

One other aspect of Ed’s daily life aboard USS San Jacinto merits mention – the Navy shower. Given the ship’s complement of nearly 1,600 officers and men, fresh water was scarce. That meant everyone took saltwater showers, and even those were limited. To take a shower, Ed would turn on the water for a few seconds to get wet, then turn it off. He would lather up with soap and turn on the water again for a few seconds for a saltwater rinse, and that was it. Still, a short saltwater shower was better than no shower at all.

Occasionally, USS San Jacinto anchored in the huge lagoon at Ulithi atoll, either for repairs as previously noted, or for replenishment and to give the crew a break. During these visits, Ed and his friends were able to go ashore to drink a couple of warm beers, play some baseball on one of the many diamonds carved out on the atoll’s islands, eat a few free sandwiches, and swim at the beach. Thus recharged, the crew would boat back to USS San Jacinto, again ready for the push toward the Japanese mainland.

During a similar stop in Guam, Ed remembers setting out with his supervisor (a Navy Chief) and his best friend, Roy Humes, to find some shoes as theirs were in bad shape. After making some inquiries ashore, they were told to take a jeep a few miles up the road to a supply depot. Doing as instructed, they came across a field where rows upon rows of F4F Wildcat fighters were parked. These fighters were the main fighter aircraft for the U.S. Navy at the start of the war, but had since been replaced by the F6F Hellcat fighter Ed was a plane captain for. They also found an open storage area with crates of supplies stacked everywhere. Eventually, they located the crates with shoes and Ed found two pairs that fit. He threw his old shoes away and put on a new pair, and then with the laces of the other pair tied together, slung the spare pair around his neck. As they prepared to depart, the supply staff told them they could not take the shoes, but the warning fell upon deaf ears. Nothing was going to stop them from finally getting some wearable shoes to take back to the ship.

As a member of USS San Jacinto’s crew, Ed participated in some of the greatest battles in naval history. In June of 1944, the ship and its aircraft fought in the battle for Saipan and the Marianas Islands, where the Japanese sent hundreds of planes to attack the American ships supporting the invasion. Dubbed by U.S. pilots as the “Marianas Turkey Shoot”, over 300 Japanese planes were shot down. It wasn’t just the Navy’s fighter pilots doing the shooting, as the guns aboard USS San Jacinto helped bring down some of the attacking planes, too. To get a sense of the closeness of the combat and the fog of war during the battle, when U.S. carrier aircraft returned to the ship at night after a late afternoon attack on the Japanese fleet, a Japanese pilot somehow mistook USS San Jacinto for his own aircraft carrier and tried to land, only to be waved off and shot down. At the same time, U.S. planes running low on fuel were also trying to land on USS San Jacinto because they could not find their own carriers in the dark. As many planes as possible were permitted to land, although some had to be pushed over the side once aboard to make room on the flight deck for the remaining aircraft trying to land. Those pilots who couldn’t find a friendly aircraft carrier to land on before they ran out of fuel had to ditch their planes at sea, hoping to be rescued.

In August and September of 1944, USS San Jacinto participated in strikes against the Bonin Islands, including Chichi, Haha, and Iwo Jima. It was during these strikes that George Bush was shot down during a raid. In October 1944, USS San Jacinto’s planes provided close air support for the U.S. landings on Leyte Island in the Philippines. The ship then fought in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the largest naval engagement in history. Again, to get a sense of Ed’s closeness to the war, as he manned his General Quarters station on the flight deck, the ship’s gunners shot down two kamikaze planes trying to sink the ship. The ship and its aircraft also provided support for U.S. forces fighting on the Philippine Island of Luzon and, during a temporary excursion from Leyte Gulf to the South China Sea, attacked Japanese airfields on Formosa and Japanese shipping in Hong Kong and Vietnam.

USS San Jacinto remained in Leyte Gulf until “Halsey’s Typhoon” damaged the ship in December 1944, requiring its dispatch to Ulithi for repairs. Then, in 1945, the ship and its planes supported the Marines in the landings on Iwo Jima (February – March) and Okinawa (March – April). The ship continued in the march toward Japan, participating in strikes on the Japanese homeland islands of Honshu and Hokkaido in July and August 1945. When hostilities with Japan ended in mid-August 1945, Ed and USS San Jacinto were operating just off Japan’s coast. After its air group flew some mercy missions airdropping food and supplies on Japanese camps holding U.S. prisoners of war, USS San Jacinto returned to Naval Station Alameda, California, on September 14, 1945. The ship was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for its wartime efforts.

Although USS San Jacinto’s war was over, Ed’s service was not because he hadn’t accumulated enough demobilization points to be immediately discharged. As a result, in early 1946, he made one more trip on USS San Jacinto to pick up and bring home U.S. soldiers from the Philippines. To accommodate the thousands of soldiers who would ride USS San Jacinto back to the States, multi-tiered bunks were installed on the hangar deck where the ship’s planes were previously repaired and prepped for battle. When the ship pulled into Manila Bay to pick up its passengers, Ed got the opportunity to go ashore and walk around. He found Manila devastated, with few buildings still standing. Despite the utter destruction, he was surprised to see Filipinos selling name brand American liquors of every type to any American who would buy them. It was a sign that even in times of despair, the entrepreneurial spirit was alive and well and that the Philippine economy would surely recover. Ed’s stay in Manila was short-lived, as the ship soon set sail now crowded with so many soldiers that it stressed every aspect of shipboard life. Just getting a meal meant waiting in line for hours, although as ship’s company, Ed had head of the line privileges.

When USS San Jacinto arrived back in Alameda, Ed, now a Seaman First Class (E-3), finally had enough demobilization points to be discharged. To make that happen, he was transferred to Toledo, Ohio, where he received his discharge papers. He then joined his family in Sandusky, Ohio, where his parents had moved and opened a small neighborhood grocery store after Ed’s father retired from working in the coal mines. Ed soon found a job building the fourteen-acre New Departure ball bearing plant, which supplied General Motors with ball bearings and began operations in June 1947. When his construction job finished, Ed was hired by New Departure as a crane operator. He worked for New Departure until he retired after thirty-five years.

Once settled in Sandusky, Ed married his wife, Jenny, and together they raised five children. Sadly, Jenny passed away in 1987. Ed later married his second wife, Pat, but she has also since passed away, as has his youngest daughter, Mary Ann. Ed is still fortunate, though, to have four of his children to share his life with.

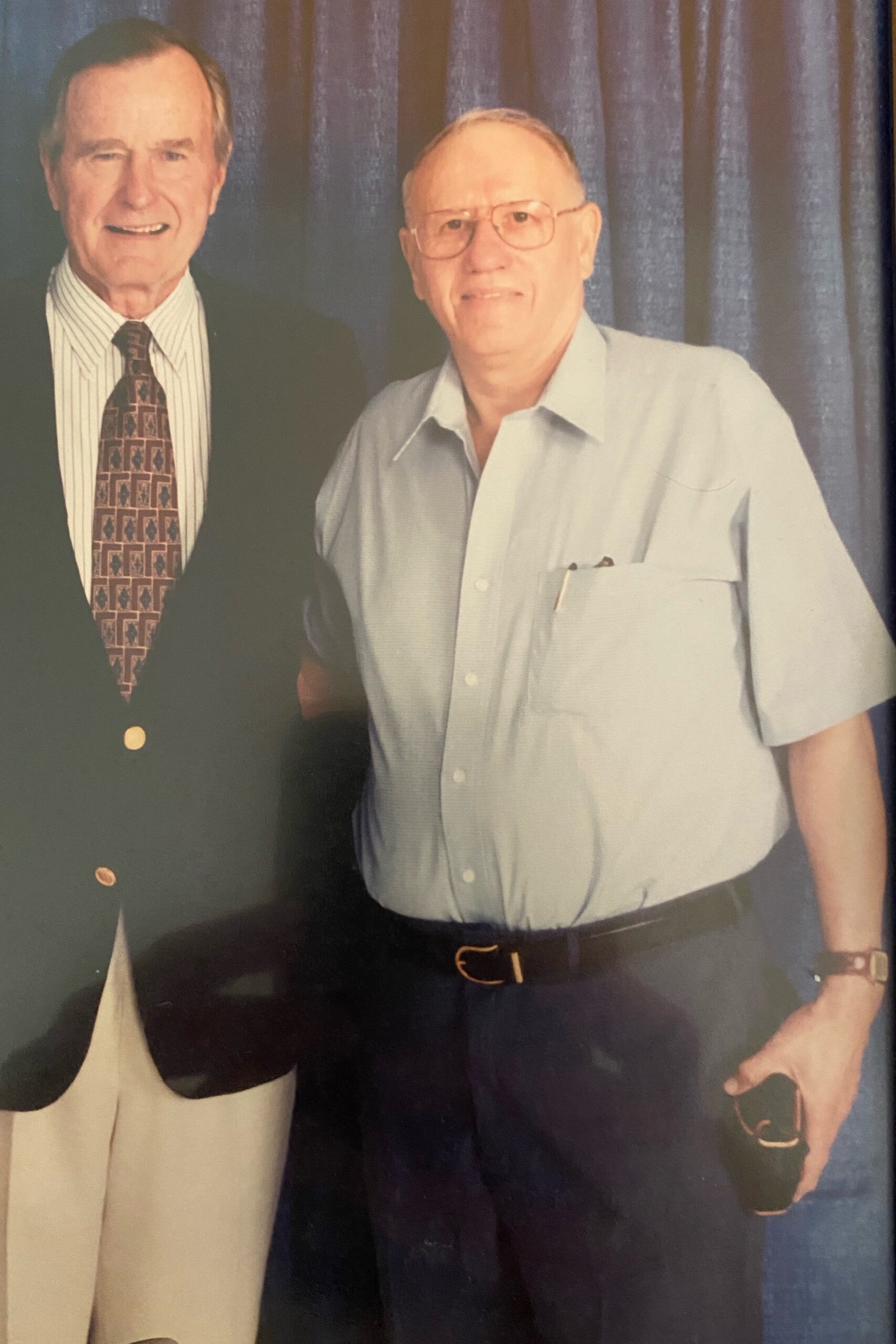

Ed’s experience on USS San Jacinto proved to be a defining experience in his life. He is proud to have served his country and for many years attended reunions of the USS San Jacinto’s crew. He even got to meet and have his picture taken with President George H. W. Bush at the reunion in 1998, which was held at the Presidential Library in College Station, Texas. When the reunions began in the 1980s, hundreds of former shipmates attended. For the 2007 reunion in Charleston, South Carolina, just eight veterans were able to attend, so organizers decided that would be the final event. Still, the friendships Ed made onboard USS San Jacinto almost eighty years ago are forever etched in his memory.

Voices to Veterans is honored to salute Seaman First Class Ed Collins, U.S. Navy, for his distinguished service onboard USS San Jacinto (CVL-30) in the Pacific theater of operations during World War II. By keeping his assigned aircraft flying and courageously defending his ship throughout months of sustained and determined attacks by Japanese forces, he directly contributed to bringing the war to a successful end. We are thankful for his faithful service and commitment to our country. Most of all, we wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Ed’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.