Sergeant Alice Gallop West, U.S. Army – Service to Others Comes First

For Sergeant Alice Gallop West, service to country and community did not end with her time in the Army—it began there. From working with the families of deployed soldiers, to giving victims and witnesses of crimes a voice in the military criminal justice system, Alice has worked tirelessly to help people and communities heal. At each step of her career, she’s learned and employed new skills to allow her to take her work to the next level. Because of Alice, our communities are safer and better prepared to take care of the needs of our military families. This is her story.

Alice was born and raised in the Ednor Gardens-Lakeside community of northeast Baltimore, Maryland, a middle-class neighborhood just a few blocks from where Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium used to stand. She was the oldest of four children and the only girl, so her father doted on her and they were very close. Her dad, who was a civil engineer, often took her to Baltimore Orioles games at the nearby stadium, passing on his love of baseball to Alice. He also took her horseback riding and ice skating, and she looked up to him and valued his guidance. Her mom was a counselor in the Baltimore City Public Schools, which Alice attended during her elementary and middle school years. When it came time for high school, her parents sent her to Elizabeth Ann Seton High School, a private Catholic school for girls named after the first U.S. citizen to be canonized as a saint.

Although Alice enjoyed her high school years and credits Seton High with preparing her to deal with the challenges she would soon face, she felt like a fish out of water. Not only was she one of the few African-American students enrolled, but she was also raised Baptist and came from a public school background. In contrast, many of her fellow students were Catholic and had attended Catholic grade and middle schools. Those factors made Alice’s life experience different. When her parents separated toward the end of her high school years, it added to her stress. Still, she made the best of the situation and was excited about her future when she graduated in June of 1982.

After graduation, Alice enrolled in Towson University, located eight miles north of Baltimore. This time she didn’t do well because Towson was not what she wanted—it was what her mother wanted. Alice didn’t know how to tell her mother Towson wasn’t right for her, so she moved out of her mother’s house in the spring of 1983 and, at nineteen years old, tried to make it on her own. After getting by for a couple of years, she decided to give the military a try.

Alice went to the recruiter’s office to enlist in June of 1985. She wanted to go Navy, but even though she’d done very well on the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery, or ASVAB, the Navy had no slots for women available until at least September of that year. The Army, however, could take her right away and even dangled a $20,000 bonus in front of her if she agreed to become a missile repair technician. Although pursuing that course entailed attending a school for a year to learn the trade, the opportunity was too good to pass up and Alice accepted the Army’s offer.

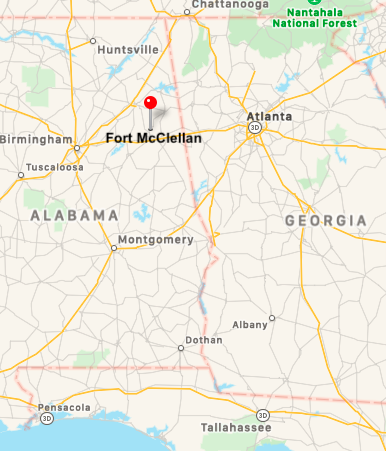

After signing paperwork in Baltimore and being sworn-in, Alice boarded a train to Anniston, Alabama, the home of Fort McClellan. All she had been told prior to departure was to take enough clothes for seven days, so she wore a white linen suit and black pumps to report in for duty, and carried a pants suit, a dress for church on Sunday, and several other outfits in her suitcase. As she got off the train, she remembers it being “as hot as Hades”. With her suitcase and briefcase in hand, she found the recruit reception station and produced a copy of her orders directing her to report for boot camp at Fort McClellan. The soldier working the desk looked at her in her white suit and gave her a look like “really?” Alice realizes now she must have looked like Goldie Hawn in the 1980 movie Private Benjamin, but at the time, she really didn’t know what to expect. When she was growing up, her family always dressed for dinner, so it was only natural for her to report for her first day in the Army in her best clothes.

The soldier at the reception desk took Alice’s orders and pointed out the “amnesty box”. She recited a list of contraband and told Alice if she had anything on the list, she should dispose of it in the box before proceeding any further. Now it was Alice’s turn to react, thinking “what kind of place is this that people come here with contraband they need to get rid of?” It made her wonder, “what have I really gotten myself into?”

As it turned out, Alice’s transition to the Army was easy. Seton High had prepared her well for the all-female training environment, and she immediately fit in and started to bond with the other forty women in her company. The training emphasized the tenets of camaraderie and good community, and the importance of helping each other succeed. For example, in the evening when “lights out” time came, the recruits would work with those who couldn’t do push-ups or sit-ups correctly, teaching them how to do them so they could get through the next day’s activities. For Alice, the physical training was fun because she was in excellent shape from three years of running and bike riding since high school. Still, she liked learning about Army values and the way the training stretched her to be the best she could be.

To move from class to class or to physical training, the recruits marched everywhere. However, if they had to travel somewhere too far away to march, a truck they called the “cattle truck” would pull up to where they were waiting and take them to their destination. The truck was aptly named because it had vertical slits for windows and the recruits had to stand in the back sweltering, packed together like sardines.

When it came time to qualify with the M16 rifle, the recruits were told if the entire company could qualify on the first day, they would get a pizza party. In anticipation of going to the range, Alice and the other recruits practiced with dummy M16s. When the day finally came, the practice paid off because all the recruits qualified. The instructors made good on their promise and Alice and her comrades enjoyed their pizza party.

Not everything about boot camp was rosy. When Alice was out in the field, the mornings could be cold and the afternoons blazing hot, making physical activity a challenge. Fire ants and their painful bites added to the discomfort. Worst of all was the water, which came out blood red when faucets were first turned on. The recruits were told it was from the red clay soil and to let the water run until it was clear. What they weren’t told was that Fort McClellan housed the Army’s chemical weapons arsenal and training site, which potentially exposed persons at Fort McClellan to chemical agents at unsafe levels.

Six weeks into boot camp, Alice got some terrible news from her Drill Sergeant – her father had just passed away from a heart attack. The Army let her go home for her father’s funeral and to help get his estate in order. Then she returned to Fort McClellan to pick up where she left off. Unfortunately, because the women she’d started boot camp with were already preparing to graduate, Alice had to “restart” with another company. She joined her new company six weeks into their training, so she didn’t have to re-do anything she’d already done. She graduated from boot camp with her new company in September 1985.

Had Alice graduated with her original company, she would have gone immediately to her follow-on missile technician training. However, the delay meant it was too late to join the course, so she stayed at Fort McClellan waiting until it was time to depart for the next class. Still grieving and with all her friends having already moved on to their Advanced Individual Training (AIT), Alice was despondent. Finally, one Sunday after church, she asked a Chaplain if she could make an appointment to talk to him. At the appointment, the Chaplain suggested Alice come by the chapel during the workday to answer the phones. That’s what she did, and answering the phones soon expanded into typing church bulletins and flyers once the staff saw how well she could type (thanks to Sister Margaret Mary Donovan’s typing class at Seton High).

It wasn’t long before the senior enlisted Chaplain’s Assistant noticed how well Alice was doing. In fact, she was doing everything the Chaplain’s Assistants were doing, yet she was barely out of boot camp. He recommended Alice consider changing her career path from missile technician to Chaplain’s Assistant. Alice took the advice and put in the request, and the Army approved it. It meant she wouldn’t get the $20,000 missile technician bonus, but she would be doing something she enjoyed. Not only that, but when she departed in March 1986 to go to school to formally become a Chaplain’s Assistant, her command awarded her the Army Achievement medal for her outstanding support to the chapel – something very rare for a soldier fresh out of boot camp.

Alice reported to the U.S. Army Chaplain Center and School at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, to complete her training to become a Chaplain’s Assistant. It was here she first realized not all Chaplains were effective faith leaders and began sorting them into three categories: good, bad, and indifferent. The Chaplain categories would remain valid for the rest of her career. She also had to learn how to properly remove deer ticks because she and the other students did their field training at the Naval Weapons Station in Earle, New Jersey, which had one of the highest concentrations of deer ticks in the country. As a result, Alice and the other trainees were always at an increased risk of Lyme disease. Finally, before Alice could be designated as a Chaplain’s Assistant, she had to pass a timed typing test. This was no problem because Alice was a skilled typist. However, when the course instructor realized Alice’s skill, she wanted Alice to take the test for some of the other students who were just learning to type. Alice was shocked the instructor would ask such a thing, especially at the Chaplain Center. She told her sergeant, but he didn’t believe her. With the instructor continuing to harass her to take the tests, Alice nearly had an emotional breakdown. She could not wait to get out of the school.

When it finally came time to leave and the assignments were being announced, Alice said she would be happy with anything as long as it wasn’t in Washington State because that was too far from home. Minutes later, Alice’s assignment was announced: I Corps Headquarters at Fort Lewis in Washington State. Once she actually reported there in the summer of 1986, she ended up loving the assignment, although she had to overcome the attitudes of some in her chain of command who weren’t used to working with women generally, and with women of color in particular. A Chaplain Alice really admired who had no such issues was Gaylord T. Gunhus, the Chaplain for the 9th Infantry Division. One day while they were driving together, Alice told him “I think you might become the Army Chief of Chaplains someday.” Her judgment of character turned out to be spot on, as Chaplain Gunhus became the Army Chief of Chaplains in 1999, rising to the rank of Major General.

In addition to assisting the I Corps Headquarters Chaplain, Alice taught aerobics at the base gym. One of her aerobics students was the I Corps commander, Lieutenant General Norman Schwarzkopf, who would lead U.S. ground forces to victory in Operation Desert Storm in Iraq a few years later. At one point when Alice got sick and had to be hospitalized, the news went across General Schwarzkopf’s desk as part of his daily brief. He directed the I Corps surgeon to call the hospital emergency room to make sure Alice, a Private First Class at the time, was okay. That made a lasting impression on Alice—the three-star commanding general cared enough about one of his soldiers to make sure she was okay, even before any of her immediate chain of command inquired about her condition. It was a lesson in leadership she would not forget.

Alice detached from I Corps in January 1988 and reported to Pyeongtaek, South Korea, for duty with the U.S. Eighth Army at Camp Humphreys, approximately forty miles south of Seoul along Korea’s west coast. Her specific assignment was with the 194th Maintenance Battalion, where she was supposed to assist the brigade Chaplain. He, however, had issues with women (and, in particular, minority women) serving as Chaplain’s Assistants, so he sidelined Alice from the moment she arrived. When he left six months later and his replacement, Chaplain Linda Ambler, arrived, Alice was finally permitted to do the work she was trained for. Alice and Chaplain Ambler were one of the first all-female Chaplain/Chaplain’s Assistant teams. They worked very well together, traveling throughout South Korea to minister to soldiers wherever they were. It was during this time that Alice learned that other students going through the Chaplain Center after she had made similar complaints about the typing instructor. As a result, the typing instructor was relieved of her duties, vindicating Alice. Finally, although Alice went to Korea single, she fell in love with a soldier there and they were married. They were able to arrange orders to be co-located at their next assignment, and they departed Korea in January of 1989.

After Korea, Alice reported for duty at the U.S. Army Armor Center at Fort Knox, Kentucky, where she supported chapel operations for two chapels. At the time, she was an “E-4 promotable”, which meant she was a Specialist (E-4) who was eligible to promote to Sergeant (E-5). While still a Specialist, Alice was selected to attend the Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course, or “BNCOC”, which was usually reserved for Sergeants and required a waiver from the Department of the Army for a Specialist to attend. Prior to departing Fort Knox to attend the course, which was held at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, Alice had to report to the Command Sergeant Major, together with all the other soldiers heading out on temporary assignments, so he could make it clear to them that they were expected to represent the command well wherever they were going. As an E-4, Alice waited at the back of the line for all those senior to her to see the Command Sergeant Major first. Things changed when the Command Sergeant Major looked at the list of people who were to see him and he saw that Alice was attending BNCOC as an E-4. He instructed that Alice be brought in first because in all his years as a Sergeant Major, he had never seen an E-4 selected to attend BNCOC. He told Alice if there was anything she needed while at the course, she should feel free to call him. Then he sent her on her way, much to the surprise of the more senior soldiers who were still waiting in line.

When Alice returned from BNCOC in the fall of 1989, she was assigned to the Family Life Center at Fort Knox. There she supported the Army’s counseling program and assisted Army families address a host of issues often relating to the deployment of a family member. Then, in August of 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait and the United States prepared to come to the defense of its ally. Now a Sergeant, Alice was called into the Sergeant Major’s office and told it looked like she would be deploying with the 19th Engineer Battalion to help repel Iraq’s invasion. Alice had to tell the Sergeant Major something she had been keeping secret – she was three months pregnant. She’d managed to keep it a secret by wearing her husband’s battle dress uniform (BDU) top and continuing with physical training along with everyone else, but the possible deployment meant she could no longer keep it a secret.

Alice gave birth to her daughter in February of 1991 and went back to work at the Family Life Center in July. Collaborating with others at the Center, Alice helped design and bring to life the Waiting Spouse Support Group Program, which provided the spouses of all the Fort Knox soldiers deployed in support of Operation Desert Storm a place of community and a space to talk about all the issues they faced in common. For example, they tackled the many family issues that arise when one spouse suddenly has to take over full responsibility for managing the family’s affairs, and then addressing the difficulties that often arise when the deploying spouse returns home. They held events for the spouses, provided day care, hosted meals, and gave kits to the families so they could write their deployed soldier. The Fort Knox program was so successful, it became the prototype for the Army’s Family Readiness Group program implemented Army-wide.

In January of 1992, Alice made the difficult decision not to reenlist after seven successful years on active duty. To Alice, being a mother to her daughter was her most important job and she felt like she couldn’t be the kind of mother she wanted to be if she stayed in the Army. Alice received her honorable discharge from the Army on January 19, 1992, and her husband received his three months later after making the same decision.

Alice found the transition to civilian life difficult, especially when it came to healthcare. By 1992, she began to suffer from a number of medical conditions which she attributes to her possible year-long exposure to chemical contaminants at Fort McClellan. Not only was the Veterans Administration medical staff unable to address the symptoms she was suffering, but Alice’s experience was they were not prepared in 1992 to deal with the medical needs of women veterans. Since then, Alice has been proactive about her health and is now getting the care she deserves.

In the years that followed, Alice had a series of life-changing events. She gave birth to her son in January of 1996 and was divorced a year later. She also completed her Associate’s degree and went to work for the Army again, this time as a civilian. She initially worked for Army Community Services and then the Army Cadet Program in Hampton, Virginia.

In 1999, Alice took a major step in a new direction and began working in the Army Corrections Program at Fort Knox as the Chief of Prisoner Administration. She also took on the role of the victim and witness coordinator. In this position, Alice fought for the rights of crime victims to make sure they knew what their rights were and that they were given a voice during the military justice process. She was also responsible for making sure sex offenders were properly registered as required by law to protect local communities once the offenders were released. In all these areas, Alice immersed herself in the regulations to make sure she knew her responsibilities inside and out—the stakes involved in protecting innocent lives were just too high.

Alice excelled at her job. In 2004, she was named the Best of the Best in Army Corrections by the American Corrections Association and the Department of Defense and received a Department of the Army Achievement Medal for Civilian Service in 2007. Her career hit a speed bump in 2009, though, when the Army corrections facility at Fort Knox closed as a result of the Base Realignment and Closure Commission. Then in 2011, the Navy opened the Naval Consolidated Brig in Chesapeake, Virginia, and brought in Alice to help stand up the new facility as the Victim and Witness Coordinator. As the Victim and Witness Coordinator, Alice was responsible for making sure victims and witnesses of military crimes knew how to exercise their rights. She was also responsible for registering sex offenders with state authorities. Alice was subsequently promoted to Vocational Director for the prisoners, helping prepare them for life after incarceration. Finally, she was reassigned to serve as the facility’s Compliance Manager, responsible for making sure the facility met or exceeded regulatory and accreditation standards pertaining to prisoner and staff health and safety, staff training, and facility security.

Alice retired from federal service in 2016. She continues to serve her community through her membership in the Elizabeth City Chapter of The Links, Incorporated; the National Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs – North Carolina; and the Virginia Dare Business & Professional Women’s Club. She is also a contributing author in the Amazon Best Seller and 2017 Indie Author Anthology of the Year, Camouflaged Sisters – Silent No More!, and is a national and international speaker and advocate for victims’ rights, veterans issues, and management of sex offender registration (visit Alice’s Facebook page to learn more). Last but not least, Alice is an active participant in Quilts of Valor, making quilts for servicemembers and veterans touched by war, and in her own ecumenical quilting group, Quilt with a Heart, through her church. Quilt with a Heart makes quilts for local charities and hospitals.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Sergeant Alice Gallop West for her lifetime of service, starting with her active duty years in the Army and extending through her volunteer service to the present day. In everything Alice has done, she has always put service to others first, whether it be helping families deal with the stress of a deployed parent or making sure crime victims and witnesses are heard in the criminal justice system. On behalf of all those Alice has helped, we thank Alice for her long career of service and wish her fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Alice’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

June 22, 2021 @ 6:32 PM

Wonderful stories!! Thank you so much!!

June 22, 2021 @ 9:33 PM

Lora – thank you so much for taking the time to read the stories – I really appreciate it!

November 13, 2021 @ 12:24 PM

Thank you so much for your service Ma’am and thank you for taking the time to read these awesome stories!

August 3, 2021 @ 6:04 PM

Thank you so much. Love each of these stories but this one was sprcial

August 3, 2021 @ 8:04 PM

Linda – I really appreciate you taking the time to read these stories and I’m glad you especially enjoyed Alice’s story.

November 13, 2021 @ 12:25 PM

Thanks Linda for stopping by and reading these stories.