Colonel Walter Joseph Marm, Jr., U.S. Army (Retired) – Battle of Ia Drang Medal of Honor Recipient

Every Soldier, Sailor, Airman and Marine wonders when the time comes, will they have the strength and courage to do their duty, even if it might cost them their life. Colonel Walter “Joe” Marm came face-to-face with that question as a young Army second lieutenant on November 14, 1965, in the elephant grass of the Ia Drang Valley in South Vietnam. For his answer, Joe Marm was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, America’s highest military decoration for valor in combat. This is his story.

Joe was born and raised in Washington County, Pennsylvania, about twenty-five miles southwest of Pittsburgh. His dad was a Pennsylvania State Policeman who spent his career in Washington County, while his mom stayed at home taking care of the family. Joe started school in a two-room schoolhouse where one teacher taught grades one through three while a second teacher taught grades four through six. After finishing second grade, Joe transferred to the Immaculate Conception parochial school in Washington County. There, the Irish nuns of the Mercy Order laid the foundation of a solid education that would carry Joe into college.

During his high school years, Joe was a member of the Frazier-Simplex Rifle Club. Shooting was a penchant he learned from his father, who was an expert pistol marksman competing for the Pennsylvania State Police. Joe used to help his father load cartridges for his father’s pistol. To participate in competitions with the club, Joe purchased a Winchester Model 52 target rifle and became quite proficient. He was also active in Boy Scouts until his troop disbanded, but not before he earned the rank of Life Scout and became a member of the Order of the Arrow. He credits the skills he learned in Boy Scouts and on the rifle team with preparing him well for the military.

Joe graduated from high school in 1959 and enrolled at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh to study pharmacy. His dad helped him get a construction job so he could earn money for school. He worked for bricklayers, loading up to twenty bricks on a “hod carrier”, which he hoisted onto his shoulder and then carried the bricks to the bricklayers who needed them. This was grueling work, as a fully-loaded hod carrier weighed about one-hundred pounds – even more when Joe carried mortar instead of bricks. One summer, they had Joe dig ditches for underground pipes feeding into the construction sites. His construction job paid $2.00/hour, a huge sum in the early 1960s. He earned even more one year working for the Jones & Laughlin Steel Company, sweeping floors and picking up trash in a steel mill.

Although Joe began his college studies majoring in pharmacy, he changed midway through to business. Normally, that change would have added a year onto his studies, but Duquesne waived the requirement that he participate in the Reserve Officer Training Corps, or “ROTC”, so he could catch-up with the required courses for his new major. Still, he knew the ROTC instructor well because the ROTC instructor coached the rifle team, which Joe participated on for three of his years at Duquesne. Joe also ran on the cross-country team during his senior year, helping him maintain himself in top physical condition.

As Joe prepared to graduate in June of 1964, his rifle team coach told him that since he was certain to be drafted, he should enlist in the Army under the college option, advising it would give him more control over his destiny. The coach told Joe if he liked the Army he could stay in, but if he didn’t, he could get out at the end of his hitch and go into business. Joe followed his coach’s advice, enlisting in the Army just five days after he graduated from Duquesne.

The Army put Joe on a train to Fort Jackson, South Carolina, where he spent three days collecting gear and signing papers. He then loaded onto a bus with other new recruits headed for Fort Gordon, Georgia. When he got off the bus, he had to use the bathroom, so he approached a sergeant and said “sir”. He got no further. The sergeant cut him off very colorfully and informed him he was not a “sir”, he was a sergeant. Once that berating was over, Joe asked where the bathroom was, which set the sergeant off again. He informed Joe that the Army does not have bathrooms, it has latrines. Joe’s Basic Training was off to a good start.

Basic Training was tough. Joe and his fellow college option recruits lived in a World War II era barracks, which they had to maintain in spit and polish condition. They also did lots of running and “low crawling”, learning the art of soldiering. After Basic Training, they continued on through Advanced Individual Training (AIT) for infantry and then finally to Officer Candidate School (OCS). At the time, OCS was geared primarily toward training existing enlisted soldiers to become officers. Because those enlisted soldiers already had a wealth of Army experience, the Army knew the college option candidates, who had no Army experience, would be at a significant disadvantage. To remedy this, Joe and his fellow college option recruits took extra classes at night and on weekends to learn about the Army and what it meant to be a leader.

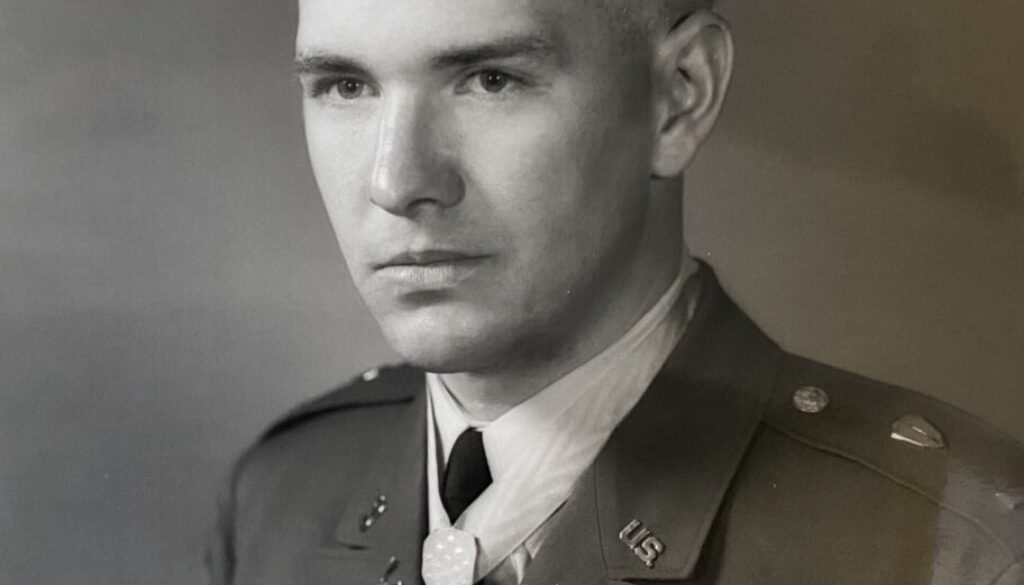

Joe was given two choices for OCS, either infantry at Fort Benning, Georgia, or artillery at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Given his Boy Scout and rifle team experience, Joe thought infantry would be the best fit. So, after completing AIT, he headed to Fort Benning in October 1964 where he joined a class of approximately 150 others seeking to become officers in the U.S. Army. Of those 150, approximately 60 were college graduates like Joe, while the remaining 90 were current enlisted soldiers whose superior performance had earned them the opportunity to become officers. The class was formed into six platoons of about twenty-five officer candidates each. The college graduates earned an E-5’s (sergeant) paycheck while at OCS, or about $145/month.

Like Basic Training, OCS was very tough. The officer candidates lived in a cinder block barracks, got haircuts once or twice each week to make sure they maintained their regulation appearance, and had to spit shine the barracks’ floors every day. To make the floor shining job a little easier, they moved their bunks out from the wall and walked behind them, rather than in the common area in front of them where they might track in dirt that could be more easily seen. Whenever they marched between buildings in the battalion area, they did so in double-time, often carrying their M16 rifles at port arms. They weren’t alone in doing so, though. The battalion commander, Medal of Honor recipient Colonel Robert B. Nett, and all of the Training, Advising and Counseling (TAC) officers responsible for training the officer candidates, double-timed too, instilling in Joe and his comrades that great leaders lead by example.

As a direct result of Colonel Nett’s and the TAC’s leadership, Joe’s OCS class developed a deeply entrenched esprit de corps. The class, which was scheduled to graduate on April 19, 1965, was the 600th OCS class at Fort Benning since it was established there in 1941. In recognition of the milestone, every time the officer candidates sat down in their classrooms, they had to recite in unison “Six-hundred classes since ’41 tried, but none will compare to 4/65.” The refrain is still engrained in Joe’s mind after fifty-five years and the bond he and his classmates forged was so strong that they continue to meet at reunions every two years to this day.

After graduating from OCS and receiving his commission as a second lieutenant, Joe went to Army Ranger School, a tough nine-week course designed to significantly enhance a soldier’s warfighting skills. The school consisted of three phases: an initial three-week phase conducted at Fort Benning, a three-week mountain phase conducted at Camp Merrill, Georgia, and a three-week jungle phase conducted at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida. Once Joe completed this intense course, he was scheduled to attend Airborne training to earn his parachute jumping qualifications. However, with one week to go in the final phase of Ranger School in Florida, Joe and about forty other officers were told they were receiving orders to report to the 1st Cavalry Division, Air Mobile, at Fort Benning, Georgia.

The 1st Cavalry Division, Air Mobile, was then in the process of testing an entirely new warfare concept in exercises against the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions. Instead of parachuting troops onto the battlefield or transporting them on the ground, the 1st Cavalry Division, Air Mobile, deployed its forces by helicopter. This resulted in significantly greater maneuverability on the battlefield, allowing forces to quickly be inserted where they were needed most and to quickly be withdrawn once their mission was accomplished. The exercises proved the validity of the Air Mobile concept, so the 1st Cavalry Division needed many new junior officers to fill platoon-level leadership positions in the new Air Mobile units. Joe and his fellow OCS and Ranger School graduates were in the right place at the right time for the assignment, so they reported to Fort Benning in July 1965.

Joe was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, of the 1st Cavalry Division, Air Mobile. The 7th Cavalry had a long and storied history, having been the unit originally commanded by General George Armstrong Custer. Aside from the newly reporting officers, the men in the unit had been training with the new Air Mobile concept for almost two years. With their recent exercise successes against the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, their morale and fighting spirits were high. Even more important for Joe, the 1st Battalion was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Hal Moore, a 1945 West Point graduate and Korean War veteran. Lieutenant Colonel Moore was a dynamic officer who led by example and was a staunch proponent of the Air Mobile concept.

With only one month under his belt with the 7th Cavalry, Second Lieutenant Joe Marm and the rest of his unit boarded the World War II era merchant ship, USNS General Maurice Rose, in Charleston, South Carolina, bound for South Vietnam. They sailed through the Panama Canal and stopped in California but were not permitted off the ship. Once they left the West Coast, they stayed busy taking classes, attending intelligence briefs on the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong, doing physical training, and practicing shooting at targets set up off the stern of the ship. Thirty-one days after leaving Charleston, and after sailing through a typhoon in the Pacific, they arrived in South Vietnam in mid-September 1965. They rendezvoused with their Division’s 400 helicopters, which had been ferried to Vietnam on Navy aircraft carriers, near the town of An Khe, which became the 1st Cavalry Division’s main operating base in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam.

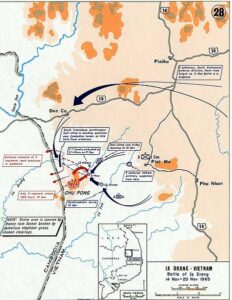

With so many troops and helicopters now calling the 1st Cavalry Division’s base at An Khe home, the immediate priority was securing the facility from enemy attack. That meant Joe and the soldiers in his platoon had to patrol the base perimeter, sometimes as part of a full battalion conducting search and destroy missions looking for Viet Cong and North Vietnamese soldiers. This continued until November, when intelligence reported that the North Vietnamese Army had established a base in the Ia Drang Valley, about thirty miles southwest of the provincial capital of Pleiku. The base, which was on and around Chu Pong Mountain, was to be used as a jumping off point for a North Vietnamese attack on Pleiku. To keep that from happening, the 1st Battalion of the 7th Cavalry was ordered to insert into and secure the Ia Drang Valley, sweeping the valley clear of North Vietnamese forces. The ensuing engagement was not only the first major battle between U.S. and North Vietnamese soldiers, but it also served to prove the effectiveness and utility of Air Mobile forces.

On the morning of November 14, 1965, Lieutenant Colonel Hal Moore flew with Bravo Company from the 1st Cavalry Division’s base at An Khe onboard sixteen UH-1 “Huey” helicopters and disembarked at Landing Zone X-Ray in the Ia Drang Valley. Bravo Company initially set up perimeter security until Joe’s Company – Alpha Company – arrived with the next flight of sixteen Hueys. Under the direction of Joe’s Company Commander, Captain Tony Nadal, Joe and his platoon took up defensive positions around the landing zone, allowing Bravo Company to move out in search of the enemy.

As Bravo Company started to engage the enemy with small arms fire, one platoon from Bravo Company with about thirty-five men moved forward in fast pursuit and got separated from the rest of the Company. They soon became cut off and were in danger of being annihilated. In the meantime, a runner came to Joe’s position and gave him a message that his company commander had been wounded and Joe was in charge. Having been prepared for situations like this at Ranger School, Joe told his platoon sergeant to take over and made his way to the Alpha Company command post. When he arrived, he saw his company commander talking on the radio. That’s when Joe realized the runner had said, “if the company commander is wounded, you are in charge”, and he’d not heard the word “if”. It was the fog of war in action.

Joe made his way back to his platoon with orders to report to Bravo Company to assist in breaking through to the lost platoon. They made an initial assault, which the North Vietnamese regulars repelled.

By now, Charlie Company had arrived at Landing Zone X-Ray, taking over the base perimeter positions and freeing up all of Alpha Company to join in a second assault to reach the lost platoon. After an artillery barrage late in the afternoon to help dislodge the enemy, Alpha and Bravo Companies pushed forward through the tall elephant grass until they were forced to take cover from heavy enemy fire. After Joe’s platoon killed four enemy soldiers seeking to dislodge them from their position, Joe saw that they were coming under fire from somewhere in front of them. To allow his men to pinpoint the source, Joe exposed himself to the fire.

Joe’s actions allowed his platoon to locate a machine gun about thirty to forty meters directly in their front, perched on an eight- or nine-foot-high ant hill fortified with rocks. After one of his soldiers tried unsuccessfully to fire a light antitank weapon (LAW) at the target, Joe took the LAW and launched a rocket directly into the mound, resulting in a loud explosion. The blast gave him and his platoon a morale boost, but the machine gun remained in action at the top of the ant hill. Using sign language, Joe directed one of his soldiers to take out the machine gun emplacement with a grenade. The soldier thought Joe meant throw the grenade from his current position, which he did. The grenade fell short, blowing up without any effect.

It was getting late in the afternoon and Joe knew his platoon couldn’t move forward without neutralizing the machine gun. Realizing he needed to take matters into his own hands, he told his men to hold their fire. He then charged directly into the machine gun’s field of fire, crossing thirty meters of open terrain until he was in front of the ant hill. He tossed a grenade over the mound, destroying the machine gun. He then made his way around the mound and using his M16 rifle, single-handedly took out the remaining North Vietnamese soldiers still maintaining their position.

With the machine gun and its defenders neutralized, Joe turned and signaled his men to move forward. Moments later, he felt the searing pain of a bullet smashing through his left jaw and exiting through his neck on the right. Fearing the worst, he checked inside his mouth to make sure he still had teeth. One of his sergeants, who had been a medic in Korea, ran up to him and patched him up enough to allow two of his men to get him back to the landing zone.

For Joe, the battle was over, but for the rest of the 1st Battalion, as well as for elements of other Cavalry units, the battle would rage on for two more days. The lost platoon was rescued, but only after many of its members were killed or wounded. The human cost of the battle for the 7th Cavalry was 79 soldiers killed and 121 wounded. North Vietnamese losses were estimated to be about ten times those numbers. U.S. air power and the tenacity of the 7th Cavalry soldiers proved to be the deciding factors in the tactical U.S. victory, but just a few miles away on November 17 at another landing zone, Landing Zone Albany, the North Vietnamese claimed a tactical victory of their own by forcing the 7th Calvary’s 2nd Battalion to withdraw after sustaining significant casualties in close-quarter fighting where U.S. air power could not be brought to bear.

Joe was medically evacuated from Vietnam and sent to Valley Forge General Hospital, an Army hospital located about twenty-seven miles from Philadelphia, to recuperate. The Army chose the location so Joe would be close enough for his family to visit. For the first three months, he ate nothing but baby food as his jaw was wired shut. However, by the middle of February 1966, he had recovered sufficiently to be released from the hospital. The Army gave him orders to return to the Ranger School at Fort Benning, this time as an instructor. Because he was a bachelor, they assigned him to the mountain phase of the training at Camp Merrill, where family housing was in short supply. While there, Joe received a letter from his former company commander, Captain Nadal, who was still in Vietnam, telling him the unit had recommended him for “a very high award.”

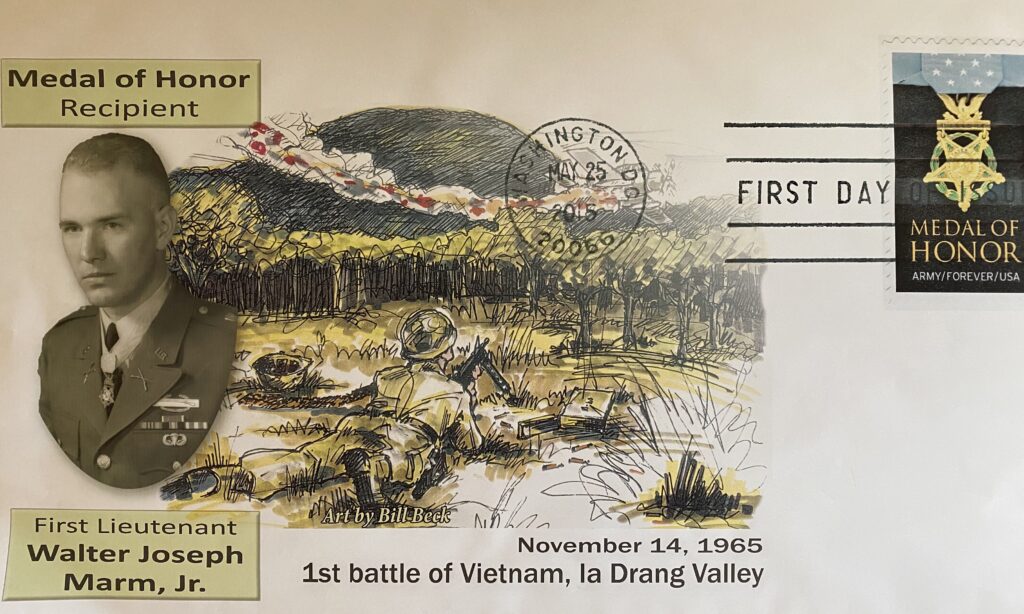

Joe subsequently participated in an award ceremony for Vietnam veterans hosted by a minor league baseball team in Florida. Joe received the Silver Star, the nation’s third-highest award for gallantry in action and personal heroism. This confirmed for Joe what his company commander had told him and he was honored and humbled to receive the award. It wasn’t until sometime later, when a reporter from Saga Magazine called Joe and asked for an interview, that Joe learned he had been recommended for the Congressional Medal of Honor.

On December 19, 1966, Secretary of the Army Stanley R. Resor presented Joe with the Congressional Medal of Honor at a ceremony held at the Pentagon’s river entrance. In addition to many generals and other senior military officers from the Pentagon, the Army flew in veterans of the Battle of Ia Drang from Fort Benning so they could see their comrade honored. The Army also sent a plane to Pittsburgh to pick up Joe’s family so they could watch the ceremony, as well. Joe remembers being in shock at the ceremony. Here he was, a young Army first lieutenant, meeting all the Army’s top officers and leaders. He had his picture taken with the Army’s Chief of Public Affairs, Major General Keith Ware, himself a Medal of Honor recipient from World War II. Major General Ware was subsequently killed in action in September 1968 when his helicopter was shot down in Vietnam during the Battle of Loc Ninh.

Joe was the seventh recipient of the Medal of Honor from the Vietnam War. Of those first seven, Joe and two others received the honor in person, while the other four recipients received the honor posthumously. In Joe’s view, his actions on November 14, 1965, were no greater than those of the many men who fought alongside him. He considers himself grateful to be authorized to wear the medal on their behalf.

Joe’s Army career did not end in December 1966. In fact, it was just beginning. As a Medal of Honor recipient, he could have served out the rest of the Vietnam War stateside. Instead, he felt obligated to return to Vietnam to be with his fellow soldiers who were carrying on with the war effort. Once he put in his request, the Army had him sign papers acknowledging he did not have to return to Vietnam and clearly stating that he was volunteering to do so. Once that was complete, Joe found himself back on a plane heading to war for a second time.

Now a captain, Joe was once again assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division. He was initially attached to the 1st Brigade Headquarters at Tay Ninh, near the border with Cambodia, as the S3 Air Operations Officer, arranging air strikes in support of troops on the ground. He later took command of a rifle company in the 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry, providing security for the base. After completing his rotation as company commander, he rounded out his second tour in Vietnam by serving as the Battalion’s S2 Intelligence Officer.

Joe’s post-war assignments were many and varied. The Army sent him to the University of Georgia, where he earned a master’s degree in psychology. He later served as a battalion commander at Fort Benning and spent the last few years of his career advising and training troops in the Army Reserve. He found his tours with the Army Reserve particularly eye-opening, watching the dedicated soldiers in the Reserve maintain their military readiness while still balancing their family life and their civilian jobs. Joe finally retired in 1995 at the rank of colonel after thirty years on active duty.

After retiring from the Army, Joe and his wife, Deborah, settled in Deborah’s hometown, Fremont, North Carolina, where they restored an old family home built in 1904. Joe also worked full-time with Deborah’s family’s hog farm. Today, Joe and Deborah are enjoying retirement together in small-town Eastern North Carolina.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Colonel Walter Joseph Marm, U.S. Army (Retired) for his incredible heroism during the Vietnam War and for his life of service to our country. He represents the best our country has to offer, humbly wearing the Medal of Honor on behalf of the men he fought alongside during the Battle of Ia Drang in 1965. Grateful for all he has given, we wish him fair winds and following seas.

Postscript: Read more about the Battle of Ia Drang in We Soldiers Once…and Young by Lieutenant General Harold G. Moore and Joseph L. Galloway. The book was subsequently made into a move, We Were Soldiers, starring Mel Gibson as Lieutenant Colonel Hal Moore.

If you enjoyed Joe’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

November 14, 2020 @ 2:16 PM

DAVE, OUTSTANDING JOB WITH COL. MARMS STORY. I AM PROUD TO KNOW HIM AND TALKED WITH HIM MANY TIMES.

THANK YOU FOR SHARING HIS STORY AND THANK YOU COL. MARM FOR THE TIMES YOU SAT AND TALKED WITH ME IN YOUR OFFICE AT WILLOW GROVE.

SINCERLY, JACK MURPHY

November 17, 2020 @ 9:43 AM

These people make me proud to be American,Love My Flag and the Soldiers that have died and protect us. Thank You from a old soldier from the 1/320th FA, 82nd Abn Div. God Bless America.

November 19, 2020 @ 9:21 PM

To Joe Marm, and all the Brave Young Men who served in Viet Nam; my undying Thanks and love! I was a Viet Nam Era Veteran, but didn’t have the opportunity to go In Country. Sometimes I feel bad about not being allowed to serve with you, but am proud to be at least been in during that time.

November 20, 2020 @ 9:09 AM

Gerald – Thanks for your service too.