Sergeant First Class Alan L. Boyer, U.S. Army – Missing in Action for 48 Years But Never Forgotten

When you are twenty years old, you feel invincible and ready to change the world. Your entire life lies before you, just waiting for you to unlock the door that will lead to your future. When it came time for Sergeant First Class Alan Boyer to choose, he never hesitated. He loved America, he loved freedom, and he loved democracy more than life itself. He chose to enlist in the Army at the height of the Vietnam War because every fiber in his being told him it was the right thing to do. Two years later, he and three other soldiers were left behind during a covert mission in Laos, leaving his family to wonder what had happened for 48 years. This is Alan’s story as told by his sister, Judi Boyer Bouchard.

Alan was born on March 8, 1946, in Chicago, Illinois, to Charles and Dorothy Boyer. Judi was three years younger than Alan and was his only sibling. Their family moved frequently within Illinois because of Alan’s dad’s job. Always focusing on the positive, Alan’s dad told his kids the moves were good because they gave them the opportunity to make lots of friends. Since Alan was naturally gregarious and a leader, he proved his dad correct. In fact, when Alan began at his third high school in four years, MacArthur High School in Decatur, Illinois, he met his very best friend, Doug Hagen, who would also later serve in the Army.

During the summers, Alan loved camping with his family, especially out west. They visited most of the western national parks, prompting Alan to get a summer job at Yellowstone National Park. He enjoyed it so much that after he graduated from MacArthur High School in June of 1964, he attended the University of Montana in Missoula, pursuing a degree in forestry. He also joined Theta Chi fraternity, making lots of friends and enjoying college life in Missoula, but there were storm clouds on the horizon. As the Vietnam War escalated in 1965, President Johnson sent more and more troops to South Vietnam to keep communist North Vietnam from overrunning its neighbor to the south.

Alan could not sit on the sidelines—he had to do his part. His father served in the Navy during World War II and their family had a strong sense of allegiance to the United States. If the United States needed young men to help defend America’s allies and promote freedom around the world, Alan was ready. He spoke to his parents, who were now living in Rockford, Illinois, and told them he had to take a break from his studies to enlist in the Army. His parents knew the risks, but they also knew how they had raised Alan and were proud of his commitment. They told him it was his decision and gave him their blessing, with the understanding he would return to the University of Montana to finish his degree as soon as he completed his service.

Alan enlisted in the Army in early 1966. He attended Basic Training at Fort Ord, California, and did follow-on Advanced Infantry Training (AIT) there, as well. After Fort Ord, he transferred to Fort Benning, Georgia, for Airborne training, where he learned basic paratrooper skills. From there it was on to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, for special forces training, where he earned the right to wear the Army Special Forces green beret.

Alan took leave two times in 1967 to visit his family. In June, he made it to Judi’s high school graduation in Rockford, Illinois. Then, after Judi followed in Alan’s footsteps and began her freshman year at the University of Montana, Alan visited Judi in Missoula and spent a week with her and those of his fraternity brothers still there. Alan’s Missoula visit is etched in Judi’s memory, not only because she adored her big brother and was thrilled he would take the time to spend an entire week with her, but also because it was the last time she would see Alan. After they said goodbye at the end of the week, Alan left for Fort Lewis, just outside of Tacoma, Washington. He was on his way to Vietnam.

Once in Vietnam, Alan was assigned to the 5th Special Forces Group, which provided highly-trained special operations soldiers to the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG) to conduct top-secret unconventional warfare missions. MACV-SOG, which employed special operations forces from all of the military services, worked closely with the CIA to conduct clandestine missions in North and South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Missions in Laos were particularly sensitive because the United States would not admit to conducting operations there. The missions were crucial to interdicting the massive amounts of supplies the North Vietnamese funneled south along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which ran through Laos along its eastern border with South Vietnam.

Typical MACV-SOG missions into Laos consisted of inserting a team of three U.S. special forces troops, together with up to twelve local operatives. The team would reconnoiter North Vietnamese activity, call in air strikes on enemy targets, and extract by helicopter, all without being detected. Other missions included insertions into enemy territory to rescue downed pilots, sorties to capture North Vietnamese soldiers to gain critical intelligence, and small team interdiction missions.

On March 28, 1968, Sergeant Alan Boyer was on one such classified reconnaissance mission near the Ho Chi Minh Trail in the jungle-covered mountains of Laos about twelve miles northeast of Tchepone, a village in the Savannakhet province. His team included Sergeant George R. Brown, Sergeant Charles G. Huston, and eight South Vietnamese soldiers. Late in the morning, the team came under fire from a larger enemy force and requested to be extracted, but when the helicopter arrived, it could not land because of the rugged terrain. Running out of time, the helicopter lowered a rope ladder into the jungle and the South Vietnamese soldiers began climbing up and into the chopper. With the eight South Vietnamese either in the helicopter or climbing to safety, Alan started climbing the rope ladder to make his escape. At the same time, the rescue helicopter came under heavy automatic weapons fire, forcing it to disengage. As it did, either the mounting brackets for the rope ladder were shot away or the rope ladder broke after getting tangled in the jungle foliage and Alan and one South Vietnamese soldier fell to the ground. As the helicopter departed, its crew observed Sergeants Brown and Huston defending their position. Alan’s status, and that of the remaining South Vietnamese soldier, was unknown.

On April 1st, a search team deployed to the extraction site to locate the four team members left behind. No trace could be found. They were declared missing at a classified location, which was not disclosed. Alan’s parents received the following telegram a few days later: “We regret to inform you that your son, Alan L. Boyer, has been listed as Missing in Action. Do not share this information with anyone other than immediate family. To do so could endanger his safety.” Several days later, two Army officers visited, but could not disclose any of the details of Alan’s disappearance. The inference Alan’s mother and father drew was Alan had been captured, so they held out hope for his return.

When Judi’s parents gave her the news, she was devastated, but she, too, held out hope Alan had been captured and would return. She had written him nearly every day since he had been in Vietnam and he had written her many letters in return. He was never able to say what he was doing or where he had been, only telling her it was scary. She knew, though, he had been trained in escape and evasion, and he was smart and in excellent physical condition. If anyone could survive, he could.

Judi went on to graduate from the University of Montana in 1970 and after a short trip home, returned to Missoula to work for the university. When the Vietnam War finally ended in January of 1973, the Paris Peace Accords included provisions for repatriating prisoners of war (POWs) held by North Vietnam. In the days leading up to their release, Alan’s parents received another telegram from the Department of Defense, this time indicating Alan would not be among the 591 POWs being released. Judi remembers as a bittersweet moment watching on TV the liberated U.S. POWs walking down the stairs leading from the C-141 transport aircraft that brought them out of Vietnam. She was so happy for the release of the American heroes but prayed as each plane emptied, “Please Lord, just let one more man walk off that plane. Please, let Alan be one of them.” Alan’s homecoming was not to be.

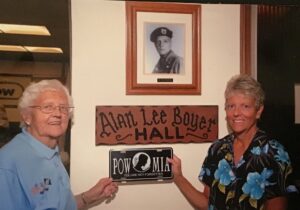

To help keep a flicker of hope alive and to gain strength and support from one another, the families of American POWs and those missing in action (MIAs) formed the National League of POW/MIA Families. Alan’s mother, Dorothy Boyer, joined the organization early on and was very active. Judi joined and was active too, and together with the other members, visited their representatives in Congress and officials at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., to promote POW/MIA awareness and make sure everything possible was being done to account for all service members still missing in Southeast Asia. They even had breakfast with President Ronald Reagan at the White House.

In the years that followed, the Department of Defense never gave up looking for Alan and Sergeants Brown and Huston, even though they had little cooperation from the Vietnamese and Laotian governments. In 1984, a Laotian refugee reported three Americans being killed and buried in the area where Alan had been left behind, but subsequent searches uncovered nothing. In 1992, the Department of Defense established Joint Task Force—Full Accounting (JTF-FA) to obtain the fullest possible accounting of those still missing from the Vietnam War. That same year, a joint U.S./Lao team traveled to the area where Alan was last seen after two local Laotians reported seeing three men fall from a helicopter in 1968. The witnesses indicated the Americans had been buried by local militia, but no remains were found. Then, in 1995, the U.S. formally restored diplomatic relations with Vietnam. Still, Alan’s case remained open. Alan’s father died in 1994, not knowing what had happened to his son.

In 2001, investigators found a tooth at an excavation site in the vicinity of where Alan’s team had been lost. Dental records linked the tooth to Sergeant George Brown and he was declared killed in action. This brought no closure to Judi because nothing about the tooth’s discovery gave any indication of what happened to Alan. She held out hope news of Alan would be found, and, after learning tour groups were now going to Vietnam and Laos, determined she and her mother would visit Laos to see what they could find out.

Judy and her mother, then 81, made the trip to Laos later in 2001. When they arrived in Vientiane, and with no advance warning, they called the U.S. embassy to see if anyone would talk to them about Alan. Their call was transferred to the Officer-in-Charge of JTF-FA Detachment Three, which worked at the embassy. Not only did the Officer-in-Charge say yes, but he also brought Judi and Dorothy to his office to talk about the detachment’s efforts and treated them to lunch. What made the biggest impression, though, was a huge photograph of the excavation site of Alan’s last known location hanging on his office wall. Since the Officer-in-Charge had no way of knowing Judi and Dorothy were visiting Laos, let alone the embassy, it gave Judi great comfort to know her brother’s case was still front and center of the detachment’s MIA recovery efforts. The trip uplifted both Judi and her mom and helped keep their hope alive.

Years passed and both Judi and her mother remained active in the National League of POW/MIA Families. In May of 2013, Dorothy passed away at the age of 92, still not knowing what had happened to her son. Then, a miracle occurred. On March 7, 2016, the night before Alan’s 70th birthday, Judi took a phone call from Michael Mee of the Army’s Casualty Operations Center. He told Judi three Lao nationals had turned in a bone fragment they found and the DNA from the fragment matched DNA samples Judi and her mother gave years before. Judi finally knew for certain Alan had been killed in Laos and she could have a proper burial for him at Arlington National Cemetery.

Lieutenant General Mike Linnington, U.S. Army (Retired), then the Military Deputy to the Under Secretary of Defense (Personnel and Readiness) and now the Chief Executive Officer of the Wounded Warrior Project, flew to Florida to meet with Judi to help make the funeral arrangements. During the course of Judi’s discussions with General Linnington, she mentioned Alan’s best friend from MacArthur High School, Loren “Doug” Hagen, had also served in the Army as a First Lieutenant after graduating from North Dakota State University with a degree in engineering. Judi relayed the reason Doug joined the Army was to go to Vietnam to find out what had happened to Alan. Amazingly, Doug was assigned to MACV-SOG, just as Alan had been, but he never found out what happened to Alan because Doug was killed in action on August 7, 1971, leading troops in action deep within enemy-held territory. For his bravery under fire and disregard for his own personal safety, Doug was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Alan was also posthumously decorated for personal bravery and gallantry in action against the enemy, receiving our nation’s third highest honor, the Silver Star, as well as the Purple Heart.

When it came time for Alan’s funeral with full military honors at Arlington on June 22, 2016, Judi was not sure whether many people would be able to attend given so many years had passed since Alan went missing in the far off jungles of Laos. To her amazement, over 100 people attended, including friends of Alan’s from MacArthur High School and his fraternity at the University of Montana, as well as special forces soldiers honoring the homecoming of one of their own. Even more amazing, Alan was being buried near his best friend, Doug Hagen. Now, the two comrades in arms could forever rest in peace together. Judi found peace, too, knowing her beloved brother was finally home.

Retired and living in Florida with her husband, Ron Bouchard, Judi remains a staunch supporter of veterans and ongoing efforts to account for the 1,586 Americans still unaccounted for from the Vietnam War (including Alan’s teammate, Sergeant First Class Gregory Huston, who recently had a stretch of Route 66 in Shelby County, Ohio, dedicated to his memory). She is active in the National League of POW/MIA Families, traveling to Washington, DC, annually to make sure lawmakers are aware of and address POW/MIA issues. She is also a proud member of the American Legion. Above all, she wants others to know what a wonderful brother Alan was and that he died serving the country he loved so much.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Sergeant First Class Alan L. Boyer, U.S. Army, for his selfless service to our country during the Vietnam War. The freedom we enjoy today is the legacy of his service and ultimate sacrifice. Voices to Veterans also salutes his sister, Judi Boyer Bouchard, for keeping Alan’s memory alive. When our nation called, Alan answered and gave it his all. May we all learn from his example.

If you enjoyed Alan’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

November 20, 2020 @ 7:09 AM

I find it interesting to know that Colonel Marm went to Immaculate Conception High School in Washington, PA. My brother and I both graduated from I.C. and my brother went on to Duquesne University and graduated with a degree in Pharmacy (1975). I went on to join the Air Force and after 22 years as an Air Traffic Controller retired and now work for the FAA. My brother unfortunately was killed by 2 gang members in the Geneva Lake, Ohio area 2 years after he graduated from Duquesne U. He had applied to be a Pharmacist in the Air Force, but due to the draw down in 1975 from the Vietnam War, he was denied.

November 20, 2020 @ 9:10 AM

Jerry – thanks for your service, too.

December 2, 2020 @ 9:16 AM

I WAS A TEACHER/COACH AT MACARTHUR HIGH SCHOOL AND KNEW DOUG AND ALAN VERY WELL. (DOUG WAS ON MY WRESTLING TEAM) I AM PROUD TO HAVE KNOWN BOTH MEN AND TO HAVE BEEN PART OF THEIR LIVES FOR A VERY SHORT TIME.

March 4, 2021 @ 4:00 PM

I was going through an old box of my grandfathers things last night. Found a copper bracelet with SGT. Alan Boyers name and date 3-28-68. My Grandfather must have known him.

March 4, 2021 @ 6:54 PM

Steve, that is really cool. I’ll pass this to Alan’s sister, Judi. Thanks for leaving the comment. I know it will mean a lot to Judi.

September 19, 2021 @ 9:54 AM

Ten years ago, or right in that time frame, I contacted an MIA support organization to receive an MIA bracelet. I wasn’t concerned with who the bracelet might represent but that I helped to keep that service member’s memory alive. That bracelet inspired several conversations, and I researched Sgt Boyer’s story so that I could share it.

I would periodically Google Sgt Boyer over the years to see if there had been any change in his status. I remember I found out he’d been identified shortly before his burial at Arlington and was immediately reduced to tears. I wanted badly to attend his service so that I could say goodbye to someone who had become very real to me and to present the bracelet I’d worn to his family. Finances prevented that from happening, so I wrapped up the bracelet and put it away with a few other things that have great sentimental value to me.

Thanks to all who refused to let go of this warrior’s name and story. Sgt Boyer is not forgotten.

September 19, 2021 @ 12:40 PM

Trent, Thanks for your comment and for preserving the memory of Sergeant First Class Boyer. I will be sure his sister sees your comment – I know she will truly appreciate it.