1LT Henry Lowenstern, U.S. Army – From Fleeing Germany to Returning in Triumph

First Lieutenant Henry Lowenstern did more than live the American dream—he earned it. After he and his family fled persecution in Germany during the 1930’s, Henry and his older brother, Leon, served in the army that helped end Hitler’s scourge. They then returned to the United States and led successful lives with their families. This is Henry’s story.

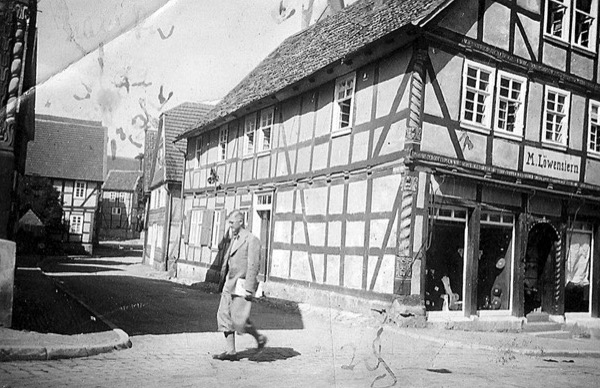

Henry was born in Korbach, Germany, in 1925, as Hans Lowenstern. His father ran a successful store he inherited from his own father, selling yard goods, bedding and clothing. Henry and Leon, then named Ludwig, enjoyed growing up in Korbach until Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany in 1933. That’s when Germany’s systematic persecution of Jews began. Initially, Henry’s parents thought Hitler was just another political hack and that he would quickly fade away, but he did not. Soon the Hitler Youth started painting on their storefront “Jews are traitors” and people threw rocks and logs through their show windows.

Henry’s father tried to prove to the town that he and his family loved Germany by copying the words from a ceremonial plaque presented to their synagogue for the ten Jewish men of Korbach, including his father’s brother, who fought and died for Germany during World War I. The inscription read “The Fatherland thanks you forever for your service.” Henry’s father displayed the inscription on a board in the store’s broken window, but the words rang hollow. In fact, Henry’s father had to go into hiding immediately after displaying the words out of fear he would be taken away. He was able to eventually return, but the situation continued to deteriorate. Henry remembers recruits for the feared Waffen SS Storm Troopers, who trained on the other side of town, marching down the street in front of his family’s store singing, “When Jewish blood spurts from the knife, things will go twice as nice.”

Amid all this hatred, Henry’s parents knew they had to escape Germany. They were able to send Leon to live in England with one of his mother’s brothers living there. Another one of his mother’s siblings lived in America and she sponsored Henry’s family to come to the United States. Miraculously, his family was able to leave Germany in the spring of 1937 and they sailed on the SS President Roosevelt, a United States Lines ship, to America. They settled in Baltimore, with Henry’s mother and father renting a very small apartment while Henry went to live with his aunt and uncle.

Henry and his parents found the people in America very welcoming. His father took a job as a floor sweeper in a necktie factory, but after a while he stepped out on his own, buying fresh butter and eggs from farmers outside Baltimore and delivering the produce to people in the city. He started delivering only to family and friends, but word spread and his service expanded until he was able to earn enough from his route to support the family. His mother initially worked as a maid until the family got on its feet financially.

Henry immediately began attending elementary school where everyone treated him like a celebrity. He learned English quickly, changed his name from Hans to Henry, joined the Boy Scouts with his cousin, and made lots of friends. He even started earning a little money of his own by going door to door to sell the Saturday Evening Post, Ladies Home Journal, and Country Gentleman magazine. Henry became comfortable with his new life in America.

After a year of living with his aunt and uncle, Henry moved back with his mother and father, who were now well-settled. He attended high school at Baltimore City College with the Class of 1944; however, given that he had completed a number of advanced credit courses, he was able to graduate in the fall of 1943.

After graduation, Henry visited another aunt and uncle, also refugees from Germany, who had purchased a chicken farm in New Jersey with the assistance of the Jewish Agricultural Society. His job was to learn everything he could about chicken farming so his parents could buy a chicken farm, too, and he could teach them how to run it. His parents did just that and after two weeks of learning the business, Henry joined his parents on their New Jersey chicken farm and taught them everything he’d learned. He didn’t have long, though, because now that he was out of high school, he was eligible to be drafted and he soon found himself on his way to Fort Dix, New Jersey, to join the U.S. Army at the invitation of Uncle Sam.

Henry in-processed at Fort Dix but spent little time there. After about a week, the Army sent him to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, for basic training in artillery. He has positive memories of Fort Sill, noting there was a good group of officers running the training. He learned how to fire the big 105 and 155-millimeter howitzers and to drive the big trucks that hauled the guns around. He also trained to become a radio operator. Dust storms occurred routinely, normally right after Henry and his fellow soldiers finished scrubbing their barracks after the last dust storm. He also remembers that Oklahoma served 3.2% beer, which, given the reduced alcohol content, made it harder for soldiers to get out of hand. The event that stands out most, though, was when a judge visited Fort Sill and swore Henry and a few other soldiers in as new United States citizens. Just seven years after escaping Hitler’s reign of terror, Henry was prepared to risk his life to defend his new home.

Before graduating from basic training, Henry applied for Officer Candidate School (OCS). The Army approved his request and, at age eighteen and fresh out of basic training, Henry began a ninety-day crash course at Fort Benning, Georgia, to become an infantry officer. He attended OCS in the fall of 1944 and finished on December 7th, just before the Battle of the Bulge raged in Europe. Infantry officer training was rigorous, especially the obstacle course. He pushed through and successfully completed the course and also qualified as a sharpshooter with the M1 carbine. The biggest challenge of all, though, was the food, which Henry describes as atrocious. He and the other officer candidates spent a lot of time at the base canteen buying snacks.

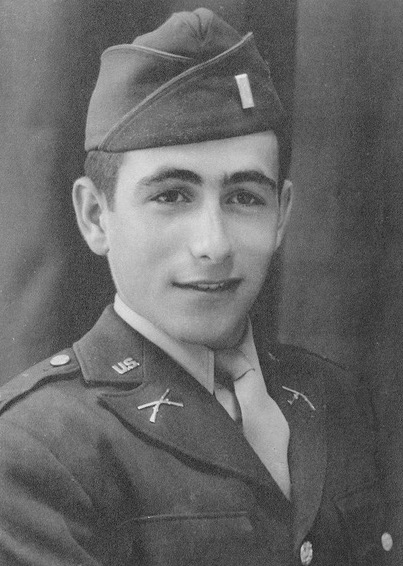

When graduation day came on December 7, 1944, all the newly minted 2nd Lieutenants were told they were shipping off to fill gaps in the Army’s platoon leader ranks in Europe. All, that is, except for Henry and one other new officer because they were fluent in German. Instead of heading immediately to Europe, they were dispatched to the Military Intelligence Training Center at Camp Ritchie, Maryland, to train as interrogators.

Camp Ritchie, located in western Maryland about sixty miles from Washington, DC, was a secretive facility few knew about and the Army wanted to keep it that way. For example, to help make the Camp’s schedule unpredictable, the Camp’s commander rearranged the calendar so each week had eight days. Another example was when the nearby city of Hagerstown’s newspaper announced the wedding of a local woman, it said only that she was marrying a soldier assigned to a nearby Army camp. Henry muses that with all that effort to keep the camp secret, matchbooks the soldiers got when they bought cigarettes at the post exchange had “Military Intelligence Training Center, Camp Ritchie, Maryland” on their cover. So much for keeping a secret!

Training at Camp Ritchie was unique. On several occasions, Henry and other trainees were loaded into a truck in the middle of the night and dropped off miles from the Camp with nothing but a small supply of food and a map written entirely in German or Japanese. Their assignment was to find their way back to the Camp, which they always did—usually with the help of local farmers. Another unusual aspect of the training was that for certain events, some U.S. servicemembers wore German and Japanese uniforms and played the roles of enemy forces to make the training as realistic as possible.

Henry graduated from the Military Intelligence Training Center in April 1945, and immediately shipped out on the French liner Normandie, which had been converted into a troop ship. After landing in Scotland, he continued to France as part of a six-man counterintelligence team. Traveling by jeep, the team drove east through Paris and eastern France, crossing into Germany on May 5th just as the war in Europe was ending. Henry comments that when the Germans heard he was coming, they surrendered.

When Henry’s team arrived in Germany, they learned that hundreds of thousands of German soldiers had surrendered and were being held by the U.S. 3rd and 7th Armies in makeshift camps that were little more than fields with barbed wire strung around them. Their team’s job was to interrogate the POWs, as well as other Germans, to determine if they should continue to be held because they either posed a threat to Allied forces or because they had been involved in possible war crimes. They operated in the vicinity of Stuttgart in POW camps near Heilbronn, Hohenasperg and Ludwigsburg.

Henry’s interrogations often followed a familiar pattern. The subject of the interrogation would claim they knew nothing about German atrocities, including the Holocaust. They also claimed they were strongly anti-Nazi. Henry then asked why they didn’t do anything to oppose the Nazis if they were so much against them. Their reply was they couldn’t because they were afraid of what the Nazis would do to them. In other words, they turned a blind eye to the Nazi atrocities committed against Jews and others but were very much aware of Nazi methods when their own lives were at stake. Henry had experienced the horrors of the Nazi regime first-hand as a boy and again during a visit to the Dachau concentration camp just after the prisoners were liberated, so he could not be deceived. When Henry’s team finished interrogating a prisoner, they turned the results over to U.S. military officials who were responsible for addressing the findings.

One person Henry interrogated was a certain Dr. Zimmerman. Henry recognized him because he had been the mayor of Korbach when Henry lived there as a boy. While Henry remembered the mayor, the mayor did not recognize Henry. Henry took the opportunity to ask lots of questions about people, streets, and events in Korbach in great detail, never letting on that he grew up there. He is certain that when the mayor left, the mayor had to be amazed at how knowledgeable American interrogators were about people and life in his small German city.

The locations where Henry worked had largely escaped the war’s devastation. He and other members of his team lived in a commandeered house and they hired a cook, so living was comfortable. He also rendezvoused with his brother, Leon, who fought his way into Germany with the 82nd Airborne Division, and they visited their boyhood home in Korbach together. When they visited their neighbor, Mrs. Tent, she was amazed to see them both all grown up in U.S. Army uniforms. She remarked, “What, you came back to fight against us?” perhaps not recalling the town’s hatred that forced them to leave.

By the spring of 1947, Henry was ready to return home. During his tour, he was promoted to 1st Lieutenant and, as the Army drew down, converted to a civilian interrogator doing the same job but earning more pay. With his work finished, he sailed back to the United States and joined his parents on their farm in New Jersey.

Using the GI Bill, Henry attended Rutgers University beginning in the fall of 1947, majoring in journalism. He wrote for the campus newspaper and served as president of a non-fraternity organization. He graduated from Rutgers in 1950, only to continue his education at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, earning a Masters degree in Economics in 1950. This led to his first job at the Bureau of National Affairs, which was a private publishing firm, specializing in tax, patent, and labor relations products, and had been under the U.S. News and World Report corporate umbrella.

While working at the Bureau of National Affairs, a friend told him there was someone he needed to meet. The friend arranged for them all to have lunch. At lunch, Henry met Martha, who Henry said he continued to have lunch with every day thereafter for sixty-seven years.

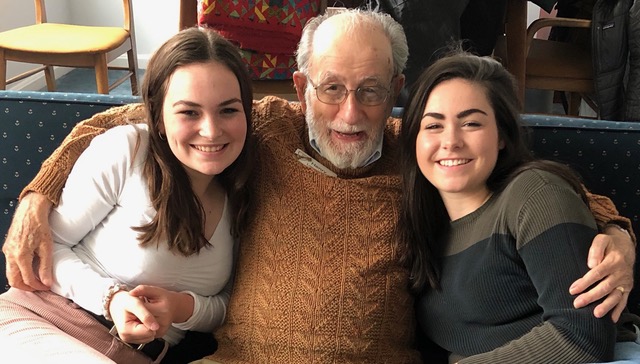

Henry went on to have a long and distinguished career in labor relations. Among other positions, Henry worked for seventeen years writing for the weekly newspaper of the Machinists Union and for twenty-two years editing the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Monthly Labor Review. He finally retired in 1991 as an Associate Commissioner of the Bureau. Martha had a similarly long and distinguished career, working for the International Labor Organization and the U.S. Department of Labor. Henry now writes daily verses he calls doggerel at his Alexandria, Virginia, retirement community, which has named him its First Poet Laureate.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute 1st Lieutenant Henry Lowenstern for his distinguished service in the U.S. Army during and after World War II. His efforts in post-war Germany helped ensure that those responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity were held accountable. Moreover, within years of immigrating to the United States, he answered America’s call without hesitation, serving in the forces that helped liberate the people of Europe from the heinous Nazi regime. We are proud of all Henry has accomplished, and we wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Henry’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

August 7, 2020 @ 10:32 AM

Thank for such a wonderful article about such a wonderful man!

August 8, 2020 @ 11:16 AM

Natalie – thanks for taking the time to read Henry’s story.

August 7, 2020 @ 9:45 PM

Thank you Mr. Grogan for telling tje story of Henry Lowenstern’s remarkable life! As a member by marriage of the family I knew some of his story but now I can really appreciate what he has accomplished even moreWe are indeed lucky to call Henry Lowenstern our cousin.

we

August 8, 2020 @ 11:22 AM

Shurley – I’m so glad you were able to read Henry’s story. To me, his life is remarkable. It’s the triumph of good over evil, the American dream, and a wonderful person all wrapped up in a single person.

August 9, 2020 @ 10:09 PM

Love the article…Thanks for your service..God bless u all.

August 11, 2020 @ 10:33 PM

Larry – thanks for taking the time to read Henry’s story.

August 11, 2020 @ 4:49 PM

Dave, always enjoy your posts. Keep up the good work my friend.

August 11, 2020 @ 10:35 PM

Dave – I really appreciate you taking the time to read Henry’s and the other stories. All of the veterans have led such interesting, inspiring lives.