Sergeant George A. Williams, U.S. Army – Drafted and Fighting in Vietnam

We’ve had an all-volunteer military since the draft ended in 1973, so it’s hard for us today to understand the life-changing impact of receiving a draft notice in the mail. George Williams knows that impact all too well. Drafted in 1965, he left small-town America to fight in the jungles of Vietnam during the height of the Vietnam War, where he served with honor and distinction. This is his story.

George was born in 1941 in Springfield, Illinois. He moved later that year to Sadorus, Illinois, a small farming community in the east central part of the state. When George was sixteen, his family moved to Stewardson, Illinois, where he graduated from high school in 1959. Unable to find a decent paying job, George headed west to live with his uncle and aunt just outside of San Francisco. He found a job working for City Transfer & Storage, packing up offices and readying them for moving trucks.

George was born in 1941 in Springfield, Illinois. He moved later that year to Sadorus, Illinois, a small farming community in the east central part of the state. When George was sixteen, his family moved to Stewardson, Illinois, where he graduated from high school in 1959. Unable to find a decent paying job, George headed west to live with his uncle and aunt just outside of San Francisco. He found a job working for City Transfer & Storage, packing up offices and readying them for moving trucks.

In 1962, George returned to Sadorus, where he took a job laying and cleaning carpets. The significance of this visit was he became re-acquainted with his longtime schoolmate, Jeanette. Carpet installation proved to be too much for George’s knees, so he returned to California and began working for a Chevrolet dealership delivering parts. This job opened the door to a forty-year career, but for now it was only temporary because George could see the draft looming on the horizon.

George married Jeanette in Sadorus in 1963 and took her to California. They moved back to Sadorus around Easter in 1965, about the same time President Johnson was escalating U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. Around November, George went into the Sadorus post office to pick up his mail. He saw three or four old-timers from the community hanging around the post office, watching him go in. There was a letter waiting for him telling him he had been drafted and to report for induction into the military on December 2, 1965. George figures the old-timers knew he was getting the letter and wanted to see his reaction.

George’s wife, mom, and dad saw him off as he boarded a bus for the induction center in St. Louis. George describes saying goodbye to Jeanette as the hardest thing he’d ever done. After passing his induction center physical, George lined up with the other draftees. An official came down the line and pointed to each man, telling him whether he was going to go the Army or the Marines. The official pointed at George and said “Army.”

George and the other Army recruits loaded onto a bus and headed west for a little over two hours until they arrived at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, for basic training. As soon as the buses pulled in, screaming drill sergeants jumped aboard and barked out orders, herding the men off the buses. That night they went through orientation, and in the morning they were assigned to the company they would train with for the next eight weeks.

George remembers basic training being miserable because it was the middle of the winter and freezing outside. In particular, he remembers having to slither under barbwire through ice cold or frozen mud and water, while live ammunition whizzed by just above him. He also remembers that although he was in great shape, being a big guy, he had trouble doing the required number of push-ups and pull-ups. When it came time for the physical fitness test, another soldier put on George’s shirt and did the push-ups and pull-ups for him. As a result, George passed the physical fitness test and graduated from boot camp.

While still at boot camp, George and all of the other recruits were given an aptitude test. One of the questions asked which is the higher caliber, 9mm or .357 magnum? George got the answer correct and when he completed boot camp, he was told he was being assigned to the artillery. He’s always joked that it was because he answered that question correctly, but he also thought it might have something to do with his age. At twenty-four, he was the “old man” of the graduating class. Most of the other graduates were only eighteen.

After boot camp, George reported to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, for eight weeks of artillery training (AIT). He completed that training and was assigned to “Charlie Battery” of the 1st Battalion, 40th Field Artillery Regiment (1st/40th), which would be deploying in about eight months from Fort Sill to Vietnam. Although the Army did not encourage spouses to accompany soldiers to Fort Sill, Jeanette moved to Oklahoma to be with George during this time and they rented a house off post. George trained almost exclusively on 105mm “split tail” howitzers, which were artillery pieces that had to be towed into their firing positions. With about two weeks to go, George trained on the M108 105mm self-propelled howitzer, which was what he would operate throughout the remainder of his time in the Army.

On September 25, 1966, George said an emotional goodbye to Jeanette, who was six months pregnant, and flew to San Francisco. There he boarded a ship en route to Vietnam. He was excited as they sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge because he enjoyed the water and the view was beautiful. But as soon as they got out of the bay, George got deathly seasick, and he remained seasick for the full twenty-four day voyage. The only way he could find relief was lying flat on his back on the deck of the ship. His buddies brought him crackers and oranges to eat—the only two things he could hold down. Although he did get out of physical training, it turned out to be a very long twenty-four days crossing the Pacific Ocean.

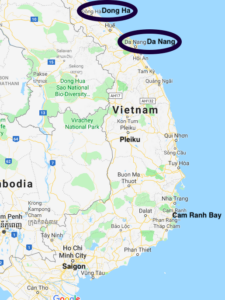

Before arriving in Vietnam, the ship stopped in Okinawa. George and the other soldiers were permitted to leave the ship, but they were restricted to a compound nearby. After living on nothing but crackers and oranges for so long, George gladly stood in line for over four hours to get a hamburger. During this stop, George’s unit, the 1st/40th, learned that they were not going to the Mekong Delta area in the vicinity of Saigon as originally planned, but would instead support the 3rd Marine Division in Dong Ha, which was very near the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between North and South Vietnam. This area saw heavy fighting throughout the war.

George’s ship arrived in Da Nang on the coast of South Vietnam in October 1966. That first night they weren’t permitted to go ashore, so George spent the evening cooped up in his berthing area, where bunks were stacked on top of one another. The whole area, now baking in the tropical Vietnamese sun, stunk of sweat, puke and men. George and the others couldn’t wait to go ashore.

George’s ship arrived in Da Nang on the coast of South Vietnam in October 1966. That first night they weren’t permitted to go ashore, so George spent the evening cooped up in his berthing area, where bunks were stacked on top of one another. The whole area, now baking in the tropical Vietnamese sun, stunk of sweat, puke and men. George and the others couldn’t wait to go ashore.

The next day they were permitted to unload, but since the ship was anchored out in the bay, they had to take small boats to the pier. George rode a small boat that looked like a World War II landing craft. As he was getting ready to disembark, he tossed his duffle bag up to a soldier on the pier. Unfortunately, just as he let go of the bag, a wave hit and George’s duffel bag with all of his belongings inside splashed into the water. Not a very good start for his first day in Vietnam.

George spent three days in Da Nang, sleeping on air mattresses in tents. While they were there, the monsoon rains started, and they woke up in the morning floating on their air mattresses inside their tent. When it came time to go, they loaded onto the landing craft with their M108 self-propelled howitzers and headed up the coast to the Dong Ha River, and then up the river to their base camp at Dong Ha.

When the 1st/40th arrived at Dong Ha, it had eighteen M108 self-propelled guns, six in each battery (Alpha, Bravo and Charlie). In addition to the turret-mounted 105mm gun used to fire a thirty-three pound explosive projectile up to seven miles, each M108 had a single .50 caliber machine gun mounted on the top of the turret. It took five crewmembers to operate each M108. George was assigned as the driver.

George’s M108s had no infantry assigned to protect them, so the men in the unit had to protect themselves. That first night, George was assigned guard duty. He was issued three grenades and three pop-up flares, but he wasn’t issued any ammunition for his M-14 rifle. As he looked out into the darkness, he swore he could see things moving around in the trees. That’s when he realized why he hadn’t been given any ammunition. Being so green, he would have shot at just about anything. Before he would be issued ammunition, he needed to be broken in with grenades and flares.

The 1st/40th’s base camp sat on a small hill overlooking Highway 1, which ran all along Vietnam’s coast. From there, George could see Dong Ha, a small village consisting of nothing but ramshackle buildings, off in the distance. The 3rd Marine Division was somewhere in the vicinity, but George couldn’t see any Marines. His unit was alone.

During George’s assignment in Dong Ha, Charlie Battery conducted numerous fire missions. For a fire mission, the battery would be given coordinates to fire upon and the guns would rain precision fire down on the enemy. Sometimes the battery would be told what the target was, sometimes it would not. Regardless, the battery’s guns were extremely accurate and they could pinpoint their ordnance right on target.

During George’s assignment in Dong Ha, Charlie Battery conducted numerous fire missions. For a fire mission, the battery would be given coordinates to fire upon and the guns would rain precision fire down on the enemy. Sometimes the battery would be told what the target was, sometimes it would not. Regardless, the battery’s guns were extremely accurate and they could pinpoint their ordnance right on target.

One mission in particular stands out for George at Dong Ha. It required George’s battery to drive about seven miles to fire on enemy soldiers attacking Marines at the top of a steep hill known as the “Rock Pile”. They had to concentrate fire on the enemy scaling the hill before the enemy could reach the Marines at the summit. This was an ongoing battle, as Alpha, Bravo and Charlie batteries would take turns on Rock Pile missions. George was only there long enough to conduct one Rock Pile mission.

About midway into George’s assignment in Dong Ha, something happened that opened his eyes to his own mortality and is difficult for him to talk about to this day. He woke up one morning coughing up blood. He’d had pneumonia numerous times before, and he assumed that’s what it was again. Eventually he made his way to an aid station. While he was there, a helicopter came in with wounded men on board. One young man, no more than eighteen or nineteen, was set on a table about ten feet from George. One arm and one leg had been blown off, and he had a big hole in his chest. Blood was everywhere and he was screaming, begging God to let him die. God granted the young man’s prayer.

After witnessing that horrific situation, George thought to himself, “What am I doing here?” He got up and went back to his unit, still coughing up blood. Several days later he was sent to Da Nang to be evaluated, where doctors diagnosed his condition as a bleeding ulcer. Although the doctors were able to treat his ulcer, watching the young man die made George realize for the first time he might not be going home. Before that, he hadn’t thought about it. Now the possibility seemed real.

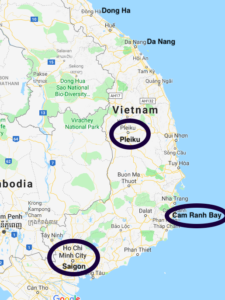

After about six months at Dong Ha, George transferred to Battery A of the 3rd Battalion, 6th Field Artillery Regiment, in the general vicinity of the town of Pleiku in South Vietnam’s Central Highlands. Battery A spent a lot of time out in the field, away from its base camp. In fact, on one occasion, Battery A left the base camp for a fire mission at a Montagnard village about nine miles away. George credits this mission with possibly saving his life because while he was gone with Battery A, another U.S. artillery unit arrived at the base camp. That same day, the North Vietnamese fired mortars at the base camp and many Americans from the newly arrived artillery unit were killed or wounded.

On another occasion, George’s unit was on a fire mission in the field when it received orders over the radio to get everyone inside their M108 self-propelled guns and close the hatches because they were about to be overrun. Once they sealed themselves inside, other U.S. artillery units began to bombard the area around them with a ring of fire to keep the enemy troops away. The friendly fire came in so close that George could hear shrapnel from the shells pinging off the armor of his vehicle. Sealed up inside, George couldn’t see what was going on outside and had no idea whether he would survive. Fortunately, the ring of fire worked and the enemy did not break through. George was safe.

On another occasion, George’s unit was on a fire mission in the field when it received orders over the radio to get everyone inside their M108 self-propelled guns and close the hatches because they were about to be overrun. Once they sealed themselves inside, other U.S. artillery units began to bombard the area around them with a ring of fire to keep the enemy troops away. The friendly fire came in so close that George could hear shrapnel from the shells pinging off the armor of his vehicle. Sealed up inside, George couldn’t see what was going on outside and had no idea whether he would survive. Fortunately, the ring of fire worked and the enemy did not break through. George was safe.

While in Pleiku, George was promoted to Sergeant and designated as his gun’s section chief. This meant he controlled everything in the gun and rode with his upper body out of the turret when the gun was driving. In this position, he could fire the M108’s .50 caliber machine gun mounted on the top of the turret. He also wore a microphone to communicate with the driver and give any necessary instructions.

George got to escape the confines of his M108 once by taking a helicopter ride on a mail run near the Cambodian border. The helicopter flew so low that the pilot had to pull up to avoid hitting water buffalo grazing in the fields. When the helicopter stopped at its destination, the crew gave the unit its mail and the unit gave the crew body count information to take back to headquarters. This was George’s only experience with the body counts that preoccupied U.S. commanders and the media.

One day in September 1967, George’s lieutenant started chewing him out for something. The chewing out was a ruse, because when the lieutenant finished, he surprised George by adding, “Williams, if you can get on that helo in ten minutes, it’s your turn to go home.” George had a number of souvenirs he’d planned to carry back with him, but with only ten minutes to pack, he had to leave much behind. Needless to say, he made it on the helicopter in time to start his journey home.

George had to wait in Cam Ranh Bay for a flight back to the United States. He got bumped three times by officers, and he didn’t sleep for three days because if they called his name and he didn’t answer, they would give his seat to someone else. Eventually he caught a flight back to San Francisco, where he stayed with his uncle and aunt for a few days, mostly to sleep. From there he flew back to Champaign, Illinois, where his wife and the nine-month-old daughter he’d never met were waiting for him. He was finally home and with his tour of duty in the Army over, he simply wanted to forget his time in Vietnam.

George had to wait in Cam Ranh Bay for a flight back to the United States. He got bumped three times by officers, and he didn’t sleep for three days because if they called his name and he didn’t answer, they would give his seat to someone else. Eventually he caught a flight back to San Francisco, where he stayed with his uncle and aunt for a few days, mostly to sleep. From there he flew back to Champaign, Illinois, where his wife and the nine-month-old daughter he’d never met were waiting for him. He was finally home and with his tour of duty in the Army over, he simply wanted to forget his time in Vietnam.

George started back to work soon after he arrived home. He settled into his job at Sullivan Chevrolet and its successor, Sullivan-Parkhill Automotive, where he worked for forty years. He finally retired in 2004 as a Service Manager.

George and Jeanette have been married for fifty-four years and they have three children and seven grandchildren. Although George left Vietnam behind long ago, he stays in touch with five brothers-in-arms who shared the artillery experience in Vietnam: Don Lawhead, Richard Svec, Jerry Zientara, Larry Ammann, and Tom Garvey. Although George would serve his country again if asked to do so, he would not wish war on anyone. War is a terrible thing to have to go through.

In looking back at his life and what he learned from his experience in the Army, George is certain that if it wasn’t for his faith in God, he would not have survived. He’s also glad his dad was a Lutheran minister—he jokes his dad might have had a little extra pull with his prayers to keep George safe.

Voices To Veterans is proud to salute Sergeant George Williams, U.S. Army, for his distinguished service in Vietnam. George epitomizes the U.S. citizen soldier, doing his duty when our country called and then becoming a pillar in his community after he returned home. We are thankful for George and other citizen soldiers like him! We wish George fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed George’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.